Gemini Rue begins with a sullen young man strapped to a rather scary-looking chair. He’s surrounded by doctors, and they’re on the verge of erasing his memory. The player is given control over a cursor, and they’re allowed to make attempts to break free, but these efforts prove futile, and the screen will soon fade to black. The game then switches to Azriel Odin (ignore the slightly silly name) on the perpetually rainy planet of Barracus. He used to be an assassin for a mafia-esque organization known as the Boryokudan, which controls much of the galaxy, but has since switched sides and now works for the police. Hunting down criminals isn’t Azriel’s prerogative, at least for the time being – instead, he’s looking for his brother, who’s been kidnapped and taken to a prison called Center 7, which is at an unknown location somewhere in the galaxy.

The viewpoint then switches back to the man in the beginning, who, of course, remembers practically nothing. His name is Delta-Six, but he prefers to be known as Charlie. He’s trapped in a facility – the very same Center 7 that Azriel is searching for – which takes criminals and “rehabilitates” them into soldiers. He had his memory blanked due to an escape attempt, or so it appears from his talks with his fellow prisoners. In between target practice sessions, he continues to again conspire to break out. As the story progresses, the viewpoint shifts back and forth between Charlie and Azriel, until eventually their stories converge at the climax.

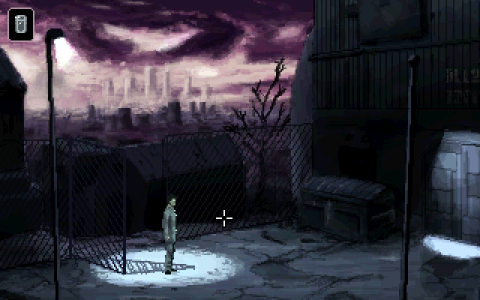

Gemini Rue is a brilliant little independent work, a piece of video game noir that obviously channels the likes of Blade Runner, but still manages to tell an original story without ripping it off. Like most titles created using the Adventure Game Studio, it runs at a low resolution of 320×200, but manages to avoid the cheapness that usually affects such products. The dark, dank backgrounds aren’t technically all that impressive, but they work to enhance the sullen atmosphere. The characters, with their blank-slate faces, look like something out of an early Delphine game like Flashback. The only negative is the character portraits, whose comic book stylings don’t quite mesh with the rest of the game’s visuals.

It’s also got some amazing sound work. The score, provided by Nathan Allen Pinard, again channels some of Vangelis’ work on the Blade Runner soundtrack: ambient and moody, but appropriately upbeat when it needs to be, with a prominent motif in many songs. If anything it’s underutilized, as much of the game is spent with just the sound of rain flooding the city. This is hardly a fault, though, considering it works splendidly to enhance the atmosphere. The voice acting, provided by the folks at Wadjet Eye, the game’s publisher, is inconsistent in quality, but the actor playing Azriel, who has by far the most speaking lines, does a commendable job.

The interface is taken more or less straight from Full Throttle – right-click on an object and it brings up a menu allowing you to look at, interact, speak with, or kick something. In a similar fashion, it’s also a fairly easy game, one that tends to favor direct approaches over fancy brainteasers. There are a few action scenes in the form of shoot-outs, all of which are handled entirely through the keyboard. It’s a bit cumbersome, as there are numerous commands to duck under cover, jump out of cover, change targets, fire, reload, and control your breathing to set up headshots. Still, compared to the arcade sequences of old, they’re easy to get a grasp on, and not terribly difficult to beat. Besides, the possibility of death is needed in a game like this to provoke a sense of danger, even though it politely autosaves before any threatening situation.

The story is well-written, even if the dialogue and descriptive text is often sparse. Azriel’s segments are the more interesting of the two, as he narrates each action and inspection. However, his personality rarely ventures beyond “gruff”. There are sparks of dry humor throughout (including a few allusions to classic adventures like Monkey Island and anime like Cowboy Bebop), but perhaps not enough to make him sympathetic to the player. Charlie, on the other hand, is a bit dry. His observations aren’t voiced, perhaps to stress the fact that he’s merely a blank slate, and he’s largely a sullen figure who’s defined primarily by the manipulations of his fellow prisoners. Center 7 isn’t as oppressively engaging as Barracus, either, and his puzzles tend to consist of dull maintenance tasks instead of detective work. As with any game featuring amnesiacs, there are a number of twists, but they’re pulled off cleverly. This all leads toward a probable outcome, subverts it, and then subverts it again. As the opening suggests, the themes of pre-destination are examined, as well as the argument of nature versus nurture. There are also some musings on the existence of the soul, and it does so (mostly) without being ham-fisted about it.

This is what makes Gemini Rue so fascinating. The look and feel is something out of the 90s, but while the genre back then tried to tell mature storylines, those efforts almost always completely stumbled over themselves. Here, designer Joshua Nuernberger manages to succeed where numerous professional developers failed, making it seem like it’s from an alternate history where the American adventure gaming scene evolved artfully, rather than collapsing upon itself.