- Genji and the Heike Clans, The

Many early 80s Namco titles, like Pac-Man and Dig Dug, were loved the world over thanks to their likable characters and their easy-to-understand gameplay. But starting with Tower of Druaga, they also became known for more complex, often obtuse styles of games, that often required the use of strategy guides, or at least some sort of communal knowledge. Owing to the difference in arcade cultures, these types of games were never released outside of Japan.

And then there’s Genpei Toumaden (“The Demonic Tale of the Genji and Heike Clans”, later known as The Genji and the Heike Clans), which has strong ties to Japanese history and mythology, both in its setting and its aesthetics. It’s one of the first (if not the first) game to use traditional Japanese characters for its score display rather than Arabic numerals, and kanji are literally thrown about as war cries. Combined to the sort of complex game design that the company had developed a reputation for, it’s as if Namco was creating a title that was completely impenetrable to anyone outside of its native country.

The game takes place during the Genpei War of the 12th century, as told in the The Tale of the Heike, a Japanese epic story and often referred to as the equivalent The Iliad. Indeed, the attract sequence actually presents the first two lines of the story. However, rather than simply wanting to control Japan, as in the actual historical conflict, here the Minamoto clan has used dark magic to rule not only the country, but the entire world. The hero is Taira no Kagekiyo, a samurai who was killed in battle, but has been resurrected in order to fulfill his mission and exact revenge for his clan. His ultimate goal is to search for the Three Sacred Treasures of Japan – the Kusanagi no Tsurugi (a sword), the Yata no Kagami (a mirror), and Yasakani no Magatama (a curved jewel). Using these, he can kill the three heads of the Minamoto clan: Minamoto no Yoshitsune, Saito Musashibo Benkei, and the leader Minamoto no Yoritomo. It’s an interesting setup, considering the Heike clans were the victors, and characters like the warrior monk Benkei have typically been presented as heroes, where here they presented as villains.

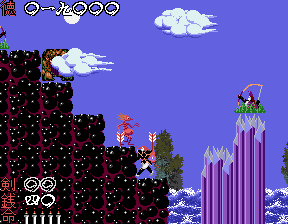

Across the game’s 40+ stages, most representing one of the old Japanese provinces, there are three gameplay modes. Most of the time is spent in standard “Small” side-scrolling areas, where Kagekiyo must run and jump to reach one of the torii gates that will lead to the next stage. There’s also the “Big” mode stages, where the perspective zooms in close, and the hero takes out about half the size of the screen. The platforming elements are mostly gone in these stages, as you simply blaze forward, take down enemies (and arrows) and typically fight a mid-boss before reaching the end. Owing to the simple layout of these levels, there’s only ever one gate at the end. Finally, there are Overhead stages, which are comparatively less common, and also usually have multiple exits.

The game literally starts at the exit of Hell, as Kagekiyo fights through a few stages before emerging on the Western end of Japan. The ultimate goal is to reach Kamakura, the capital of Japan in the 12th century (and reasonably close to Edo/Tokyo). The gate you take at the end of a level will determine the next stage. There are a few different routes through the game, some more difficult than others. You’re not given any clues as to the location of the three treasures, so it’s very easy to blunder around if you don’t take a look at map of how all of the stages connect. You can also miss the treasures even if you’re at the necessary level, so you won’t be able to beat the final boss even if you reach him. Two of the treasures can be found in two different places (the Magatama at Settsu or Ise, the Mirror at Echizen or Ecchuu), while the Sword can only be found at Shinano. So all of this is relatively complex – not as much as, say, Namco’s infamous Tower of Druaga, but there’s a lot here for an arcade game from 1986.

The actual gameplay is…well, it’s a little unusual. In the Small side-scrolling, Kagekiyo controls rather unusually, in that he’ll walk for a step or two before increasing speed into a run. This also determines your jumping strength, so if you don’t build up a bit of steam first, then your leap won’t have much of any reach. The basic sword slash has extremely low range – there are power-ups that let you fire waves, but you don’t always have them – and getting hit will send you flying, giving the game a very bouncy feel. There are a few cases where you even need to jump on enemies and ride them in a bit in order to make it over tall landscapes. Many stages have floating rocks, some of which will bound around haphazardly, others of which will drop down from the sky to smash you, or politely move back and forth. You’ll need to jump on these, but Kagekiyo’s feet doesn’t really connect to them, particularly the ones moving horizontally, so you need to walk along with them or else you’ll plummet to the ground. Enemies attack quickly, often careen right through the scenery. The action regularly tosses way more than the CPU can actually handle, resulting in short but regular bursts of slowdown, which, combined with the awkward movement, which creates a game with a very jarring tempo.

All stages have impressive parallax scrolling, but there are also added background elements, like the animated faces in the ground in the hell levels, or the clouds scrolling by in most other stages. Time transitions from day to night (extremely quickly) and in levels where you can see the sun or the moon, it will even rise and set in the background. The level titles aren’t displayed in the center of the screen like in most games, but rather as floating elements on the game field, that scroll away as you run past them. Whenever you die, you don’t just fall over, but your whole body explodes outward, limbs flying in all directions, at least in the Small mode. After this happens, a gigantic kanji reading “END” falls from the sky. Plus, the speed is quite fast, and combined with the odd controls, it make everything feel like a bizarre fever dream.

The Big mode levels are similarly messy, but in different ways. Kagekiyo’s sprite consists of a few parts that move independently, the only way to assure smooth animation in an 80s arcade game with limited memory. There are a couple of different sword moves, too, depending on which direction you tilt the joystick when you attack. The goofiest is when you get a power-up scroll, which causes Kagekiyo to spin his arm around continuously like a buzzsaw. This is a hugely powerful move and it’s a lot of fun to mow down enemies with it, but it looks ridiculous. At any rate, these levels do feel a little same-y because there are only a handful of mini-bosses.

Everything about the animation and the hit detection just feels bizarre, but luckily Kagekiyo can absorb a fair amount of damage before he’s killed. His life meter is represented by candles, which slowly melt and fade away as he takes damage, and are typically replenished to some extent when beating a level. You only have a single life, but in the first half of the game, you just restart the stage when you continue. This is pretty generous, but unfortunately, once you reach Kyoto, which is about halfway through the game, this becomes the last checkpoint. In other words, any time you die after that, you’ll be tossed all the way back there, which can be several stages.

Throughout the stages, you’ll also be picking up two kinds of power-ups – swords and money. The sword icons increase your weapon strength, which in turn can make the mini-boss fights much easier if you’re powered up. Conversely, if you strike objects which are too thick (rocks or other armored things), you’ll decrease your sword power – you can actually see it get bent and broken in the Big levels. There are no shops in the game, but instead money is required when picking up a few kinds of specific power-ups, which can quickly increase your sword strength or heal you. If you have enough cash, you can also easily escape from the pit level without taking your luck with being judged. Additionally, the three treasures aren’t just useless trinkets – the Sword will prevent your weapon from every getting damaged and losing strength, the Mirror will make you immune to thunder attacks, and the Magatama will protect you from poison.

Most of the Small side-scrolling stages are pretty similar, but there are a few gimmicks in the levels, such as mini-boss fights with flying dragons, and bonus stages where the sun goddess Amaterasu drops a litany of power-ups for you to grab. In a few areas, a gigantic Minamoto no Yoritomo will pop up in the background and try to thwack you with his fan. There are also a few gags stages which include appearances by the game staff. The game also has a number of hidden stages which can be accessible via the board’s dip switch, though some of them are glitched as they are clearly unfinished.

The Genji and the Heike Clans feels like a janky mess, but it’s hard not to admire its ambition. Its scale is incredible for a mid-1980s arcade game, and while the levels do get repetitive, they’re fairly short, and the constantly changing perspective ensures that the action stays fresh on a moment-to-moment basis.

During this time, Namco was experimenting with giving “character” to its games, which mostly resulted in cutesy or comical titles like Wonder Momo or Bravoman, but here it’s much darker and foreboding, with both the visual design and the soundtrack exude a strong Japanese atmosphere unseen at the time. It has a weird energy that becomes entrancing the more you spend time with it.

The game’s ending includes a poem that’s actually a tribute to two Namco programmers. The opening line says that “God is dead, the devil has left”. “God” refers to the nickname of Shouichi Fukutani, who worked on titles like Dig Dug, and was a well loved mentor among the staff. But he suddenly passed away at the young age of 31 due to liver rupture. “Devil” refers to Kazuo Kurosu, who worked on Rally-X and Mappy, among others. He left the company along with Xevious developer Masanobu Endou to form Game Studio, who continued to work with Namco for a number of other projects, but was still missed by the staff. While dedications are common in Western media, these are atypical in Japanese products, especially in video games. The arcade ending includes text explicitly dedicated to Fukutani – this was removed for the PC Engine version, though the rest was kept. Several other Namco games also include dedications to their departed mentor.

There’s also an amusing allusion to a classic Japanese arcade game. In the Kyoto stage, you’ll fight against weird looking four armed pink creatures with gigantic mouths. These are called Heiankyo Aliens, based on the 1979 game of the same name. (It’s a little hard to make the connection considering how simple they looked in the original game, but you can see the vague resemblance.) The game takes place in Kyoto, hence why they only appear in this stage in The Genji and the Heike Clans.

As far as ports, the X68000 port released in 1988 is basically arcade perfect. The PC Engine port released in 1990 is pretty solid. The color palette has changed a bit so it ends up looking a little brighter, some of the background details are missing (like the day/night transitions) and the UI has been rearranged, plus the music and sound effects aren’t quite as good. Some of the enemy’s attack patterns are different, and Benkei’s weakpoint has changed from his head to his legs. But otherwise, it replicates most of the game faithfully.

The first (and only) time the game has appeared in English is on Namco Museum Vol. 4 for the PlayStation. This version translates (most) of the text, changes the numbers of Japanese to Arabic, and makes a few other UI modifications for the sake of readability – for some reason, the source of currency has been changed to gems. Without any context to what this game was, and only a few screens of instructions buried within the in-game museum, it was a perplexing inclusion at the time, though perhaps with some better understanding (and modern strategy guides on the internet) can be more fully appreciated. The PC Engine exclusive sequel was released in America under the name Samurai Ghost.

There was also a live action trailer created to promote the game. It’s obviously pretty low budget, and the actor for Kagekiyo is blond here for some reason (though has proper red hair in the illustrations), but it’s good cheesy fun, and has cool arrangements of the theme music. It was directed by Keita Amemiya, a designer for many anime and video games, and also later with Namco on the movie/video game collaboration Mirai Ninja (AKA Cyber Ninja). An edited version of this video is hidden on the Namco Museum Vol. 4 disc.

Genpei Toumaden did inspire a few other games – Konami’s Famicom game Getsu Fuuma Den is quite similar, right down to having an undead hero with long red hair, and Sega’s Master System game Kenseiden also borrows some elements, including the non-linear exploration of feudal Japan. Only the latter was released outside of Japan.