More than any other genre in video game history, the graphic adventure has always been carried by significant personalities, the fictional characters on screen as well as the creative heads that brought them to life. Most adventure games are identified with definitive auteurs, names that mean much to fans even today. The late ‘80s changed all that though. The desire to destroy was greater than ever before, while solving problems using one’s brain was out of fashion. Then the second half of the 2000s came and the global video game market regained its ability to sustain niches beyond all that ever-so-marketable slaughtering.

Yet when previously popular adventure series also made a comeback, disappointment often followed. For example the return of Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis creators Noah Falstein and Hal Barwood, with Mata Hari, received a lukewarm reception from fans and critics thanks to plot holes and light puzzles. Understandably then, gamers’ feelings towards Jane Jensen’s big new game shifted between hype and fear. Her classic trio of Gabriel Knight mystery thrillers stands as one of the most outstanding examples of storytelling in video games. Jensen’s year-long work in casual games, however, instilled worries in those who valued the Gabriel Knight series for its well researched plots, believable characters and challenging puzzles. Despite her casual gaming venture, a number of well-received mystery novels she wrote in the meantime served as proof that Jensen never lost her touch.

Her new game was codenamed “Project Jane-J”, but after being announced at E3 2003 through The Adventure Company, it was suddenly left hanging. According to Jensen most of the story was already finished. It would take three more years before the game resurfaced as Gray Matter, now under the wing of German publisher dtp Entertainment, who had made a name for themselves by releasing many prestigious adventures from all over Europe.

The actual development was outsourced to Tonuzaba in Hungary, but after several delays the publisher decided that they didn’t have what it took to deliver what was possibly becoming the most anticipated adventure game of the decade. After another period of uncertainty, the French developer WizarBox was hired to complete Jensen’s vision. With an adventure portfolio consisting solely of So Blonde, WizarBox didn’t inspire confidence.

More delays followed, but the game started to make steady progress and in November 2010 finally saw its release. Initially only in Germany, international versions followed in early 2011. The question was: after all those years of development could Gray Matter – perceived as the spiritual successor to Gabriel Knight – fulfill gamers’ expectations? Or had Jensen’s intuition for deep plots and clever puzzles been spoiled by years of casual game development?

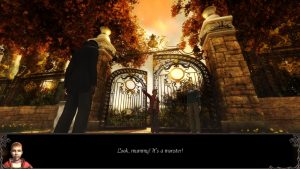

Initially things don’t look promising. We see a woman on a motorbike trying to reach London. It’s raining as if the big flood has just begun, and the storm turns around a signpost, leading her in the wrong direction. The woman’s motorbike breaks down, of course, just in front of a dark and spooky mansion. Stepping up to the gates our heroine arrives just in time to witness a girl standing outside and practicing her introduction line: “Hello, I’m the new assistant of Dr. Styles.” But something scares her so much that she immediately takes to her heels.

Anyone who knows horror films, and recognizes the signs, would do the same as the girl. Yet astonishingly our protagonist, despite the atmosphere of immediate threat, decides to take the fleeing girl’s place as Dr. Styles’ assistant – not for long, of course, just until she finds out where the girl ended up. Although it seems ridiculous to cram so many clichés into the first few minutes of the game, Gray Matter knows exactly what it’s doing.

Samantha Everett is our protagonist’s name. A runaway orphan from the United States and a street magician, she has traveled through all of Europe on her own, heading for London to find the world’s most secret society of magicians, the Daedalus Club. She plans her stay at the Dread Hill House – as the aforementioned assistant – to be only temporary. The job, however, pays fantastically and, arranged as it was through a student job agency, the residents know next to nothing about the applicant. Such auspicious conditions seduce Sam to stay just a while longer. First repelled by Dr. Styles’ gruff mannerisms, she is soon intrigued by the unique and tragic fate of her new employer, and feels a certain connection to her own past.

Dr. David Styles takes over as the playable character for the shorter three of the game’s eight chapters, to deal with his inner demons and push forward his experiments. He used to have it all: wealth, popularity, a promising career as the world’s top neurobiologist, and a beautiful wife. But a car accident which happened under mysterious circumstances, three years before the events of the game, ended all that. With his wife Laura dead and the doctor himself disfigured by severe burns, he retired from the university and locked himself up in his mansion, ordering his housekeeper Mrs. Dalton never to change anything in the house that serves his memory of Laura. Convinced that Laura’s mind still remains around him, he has become obsessed with the desire to get through to her. Despite having the reputation of a mad scientist, he decides to continue his former research on the potential of the human mind to directly alter the physical world, in the hope that it will help him to find a way to communicate with Laura.

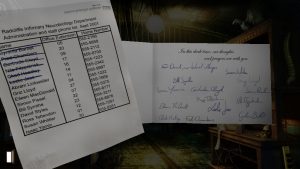

After a tutorial to familiarize player with the game’s controls, Sam’s first assignment in her new position as David’s assistant is to find six voluntary human test subjects. Not an easy task, given how infamous Dr. Styles has become among students over the years. Yet she soon finds her targets among the university’s freshmen, who are ignorant of his reputation. She convinces fellow American and amateur filmmaker Harvey Kinderman, the vain rich kid Helena Beauregard, the shy but incredibly good-looking mummy’s boy Charles Ettington, and the superstitious Scottish bumpkin Angela Mulholland to participate. Though they are not as many as asked for, Dr. Styles can’t hide his surprise that Sam found anyone at all. He himself has recruited another test subject, a quiet student from abroad named Malik, while the sixth is going to be Sam herself. Through their connection as the mad scientist’s guinea pigs the six former loners form a kind of clique: The Lambs’ Club.

Sam’s method of winning the hearts of her acquaintances is magic tricks brought from her “profession” as a street magician. These account for a good portion of the puzzles and are supposed to be Gray Matter’s big new thing. When it’s time to “trick” a person, the talking icon switches to a magic hat. Sam then has to select the appropriate trick out of a dozen from her spell book, and apply it to the given situation by using commands to “palm” items in her hand, “vanish” them up her sleeve and so on.

Unfortunately, most of the time the solution is quite simple, and demands no more than following the instructions in the trick description. To help Harvey get back his documentary from a girl he filmed in an unfavorable situation, for example, Sam has to switch it with an empty tape while casually playing around with it, then destroy this fake tape in front of the girl’s eyes. This kind of puzzle would open a lot of interesting opportunities if its setup was less dogmatic and more demanding of adaptive thinking. The way it’s implemented, however, the trickery is no more than a nice but unexciting distraction.

For some of her tricks Sam needs special props from a magician’s supply store, where she stumbles upon a link to her original goal of contacting the Daedalus Club. She meets the sly and charismatic Mephistopheles, who tells her a lot about the society, including the “Grand Game” anyone who hopes to enter has to perform: a large scale scheme of remarkable trickery. In his store Sam also finds one of the club’s puzzle boxes, which sends her on a scavenger hunt to win her spurs in the eyes of the club. There are two such hunts in the game, each of which stretches over two chapters and focuses on traditional riddles like rebuses and word play.

There are also “normal” adventure puzzles in Gray Matter that revolve around the manipulation and combination of items. The solution is almost always practical and requires little outside-the-box thinking (on the plus side though this means the puzzles don’t feel too constructed). Apart from the few harder puzzles in the final stages of the game, veteran players might mourn the lack of a truly brain-teasing challenge. Here’s probably where Jensen’s casual game influence comes into play, since in contrast to the sometimes really tricky puzzles in Gabriel Knight, pretty much everyone should be able to complete Gray Matter without a walkthrough – but not without stopping to think every once in a while, mind you.

While the solutions to puzzles often lead back to previously visited places, backtracking is never much of a hassle as a map of Oxford allows for fast travel. On the map, names of locations still relevant to the main plot are rendered golden and places finished for the current chapter are grey, narrowing things down. Some names appear in silver/white, which means that there are still bonus points to be gained there even though they don’t serve to advance the main plot anymore. At one point (in chapter 6), it’s possible to sequence-break by using the map, which doesn’t break the game but makes for a weird backwards progression of certain events.

Bonus points represent an updated return of the scoring system from the Sierra days of adventure games: every correct action is rewarded with points, some of which are completely optional. In chapter 2, for example, Sam can buy flowers from an old lady in town, which she may use to decorate certain places in Dread Hill House to make the place less dreadful. While such simple things don’t affect the main plot at all, they can feel quite rewarding in themselves.

But what about the story? After throwing players into the setting quite abruptly (although Jensen wrote a story introducing readers to Sam’s life in 2008), the plot develops rather slowly. But after strange phenomena start appearing during Dr. Styles’ laboratory “mind exercises”, Gray Matter has one captured entirely under its spell. Not much in video game storytelling has ever been as intriguing as the way Sam and David discover links between past and present incidents. While David is looking for messages from his deceased wife in those “pranks”, Sam is wavering between suspecting a plot against Styles and the assumption that one of the students might be conducting a Grand Game to gain entry to the Daedalus Club.

What soon ensues is a masterful character-driven mystery that manages to play out the personalities of the cast to great effect. Switching between two protagonists brings interesting insights from their perspectives, which is especially noticeable when the two meet in direct confrontation. The at first awkward dynamics between the outspoken street artist and the embittered scientist that grow closer over time ever so subtly are certainly the high points of the writing, but the supporting characters are no slouches either, even if some have a slight tendency to devolve into stereotypes. The extensive research which made the Gabriel Knight games such convincing pieces of fiction also shouldn’t go unmentioned. At the end of Gray Matter, the player will have learned quite a bit about the history of Oxford, mythology and parapsychology.

Humor is when a supposedly serious game like Gray Matter sets out to school all the other “funny” games about humor. Despite its often grievous topics, the story always finds time for the bright side of life, and many of the characters are blessed with a genuine sense of humor. Their jokes are always in-character, which sets them apart from the one-liner machinations many adventure game protagonists have degraded to.

However, even the greatest adventure games developed in France, Germany or the Czech Republic suffer on the international stage from lackluster English localization. Here Gray Matter thankfully is on the safe side thanks to Jane Jensen’s authorship. Not only is there no such thing as a translation loss, but Jensen personally took care in the quality of the English dub, overseeing both the casting and production. With very few exceptions even the smallest characters deliver their roles convincingly. With its fairly international cast, a lot of care has also been placed on the various accents, often a sore thumb in adventure game dubs.

Like in all three Gabriel Knight games, the adventuring is once again accompanied by a soundtrack composed by Jensen’s husband Robert Holmes. Most of the time the arrangements are decidedly low-key, but fit the scenes on screen extraordinarily well. The three major themes in the game are performed by Holmes’ band The Scarlet Furies, which couldn’t have been chosen more perfectly. Their moody, sometimes melancholy sound hits the nail on the head when it comes to complementing the game’s emotions.

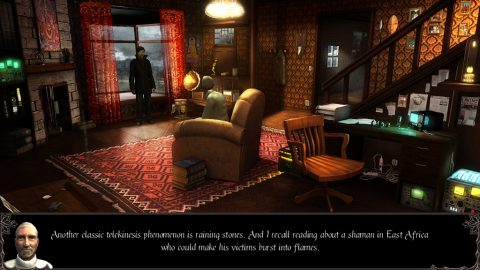

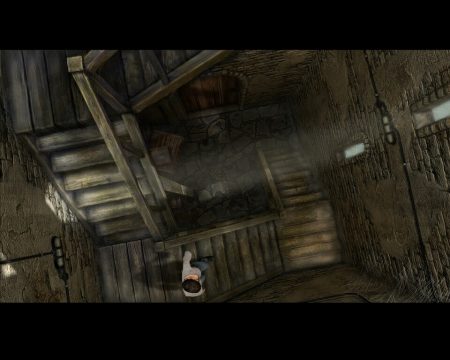

Polygonal characters in front of mostly static bitmap backgrounds have become kind of a standard for the adventure genre, and Gray Matter makes no exception here. Elaborate lighting techniques do a great job to set the mood and create a rather convincing illusion that both layers belong to the same world; only on a few screens does it become visible that the characters are hovering in front of a flat plane. Despite the whole game taking place in and around Oxford, Sam and David visit many locations with very different scenery and atmosphere. Some bathe in grandeur like the stunning view in Headley’s office or the top of Carfax Tower, while others feel deserted and claustrophobic. In the endgame it gets all crazy and surreal, too. The game also conveys a strong sense of authenticity. One can hold photographs next to the more famous locations in Oxford and try to spot the differences.

On the downside, there are a few obviously unfinished animations. At times there are also clipping errors when characters directly interact with the 2D background. All of these are few and far between, but constitute the most disturbing failures in the visuals. The cinematic direction outside of cutscenes also feels dated – it’s grating when screens constantly fade in and out because doors are immovable. There isn’t much to see in terms of facial expressions, either.

The controls take the inevitable streamlined single-button approach, complete with all comforts the genre has developed over the past decade. A double click causes the protagonists to hurry to their destinations, while inventory items are readied with a right click and then used automatically when interacting with the right object. Sam and David also each maintain a notebook, but it just documents all the dialogue lines. Gray Matter also makes use of the space key as a toggle to show all hotspots on screen.

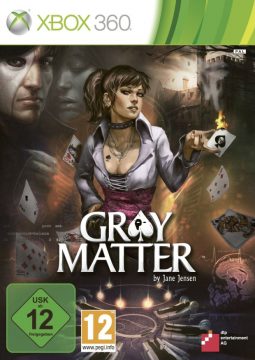

Nowadays even adventure game publishers have to take consoles into account to grant their games commercial viability, but instead of going for the obvious Wii port in addition to a Windows version, Gray Matter was co-developed for Xbox 360. This was only available in Europe and dtp lamented the lack of publisher interest in releasing the Xbox 360 port stateside.

The inferior lighting effects for the console version are criticized much, but while the game looks better with the highest settings on PC, the differences are marginal. The real problem of the console port lies with the controls; the designers really went out of their way to create the most stupid control scheme imaginable. Characters are controlled directly with the left analog stick, which only works as long as one never changes direction, otherwise they get caught on nothing but thin air. In order to interact with hotspots, a radial menu for the nearest hotspot is opened by holding the right trigger. The game tries to arrange the allocation so that it corresponds with the actual hotspot’s location, but given that there are only 16 slots available at fixed angles, more often than not it doesn’t work out at all. All this is made even more ridiculous by the many close-up screens for things like drawings and letters, which use perfectly functional point-and-click controls that are of course unavailable for the core gameplay. When given the choice between the two platforms, the PC is strongly recommended.

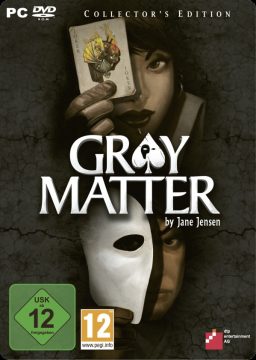

Unlike the Xbox 360, the PC was also graced with a special Collector’s Edition, containing the excellent soundtrack on an extra CD, a poster which is unfortunately folded in a way that makes it useless, a deck of 55 Gray Matter-themed playing cards and a few postcards with motives from the game and concept art. Not the most bombastic special edition ever, even less so as the manual is ugly black and white, but the soundtrack alone is enough to make the package worthwhile. Granted, it’s also available separately via digital distribution for less than the price difference of the CE. Unfortunately, the special package was only published in Germany, but the disc contains full English text and voiceover, so there’s always importing.

Contrary to what some may have secretly wished for, Gray Matter is not a Gabriel Knight 4 in disguise. Its story sets a different tone, and the puzzles take a more accessible approach than those from the golden age of graphic adventures. Those who dared hope for the perfect adventure game will also be disappointed, as the title is not without its fair share of rough edges. Although more driven through its fascinating plot and vivid writing than by genius puzzles, Gray Matter is nonetheless above far among its contemporaries in either discipline. While there have been quite a few adventure games with decent puzzles over the last couple of years, what the genre was really starving for was a new excellently written game, and that’s exactly what is delivered here. Everyone who’s into adventure games is finally in for a real treat.

What’s left is to hope is that we won’t have to wait another 11 years for the next full-blown adventure by Jane Jensen. The ending of Gray Matter does indeed hint at a possible sequel and leaves enough open ends to follow up on the story. The author herself has proclaimed interest in making this the start of a new series. If what this game achieves is any indication of the things to come, and its commercial success secures more follow-ups, the future of the genre might look a little brighter than it did in the past dozen years.