“With bony hands I hold my partner

On soulless feet we cross the floor

The music stops as if to answer

An empty knocking at the door

It seems his skin was sweet as mango

When last I held him to my breast

But now we dance this grim fandango

And will four years before we rest.”

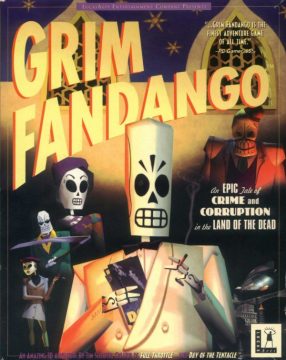

According to Aztec mythology, most departed souls are not easily admitted into the afterlife. Instead, they are subjected to a four year journey fraught with perils. LucasArts’ Grim Fandango takes this concept and runs with it, by introducing a karmic twist – people who led good lives can take a ridiculously expedient train that boils the travel time down from four years to four minutes. Lesser folks are handed walking sticks and told to be on their way. The division in charge of these decisions is the Department of Death, who employs a series of grim reapers – or, as they prefer to be called, travel agents – to provide the proper passage.

Manuel “Manny” Calavera is one such travel agent. He, along with everyone in the department, are lost souls, unable to proceed to the afterlife until they have paid off an unnamed debt. Unfortunately, he works on commission, and all of his clients are low-lifes unable to afford the better modes of transportation. As Manny quickly learns, it’s not for lack of trying, as his co-worker Domino seems to be getting all of good clients. Feeling that something is suspicious, Manny intercepts one of Domino’s potential clients, an altruistic young woman named Mercedes “Menche” Colomar. She should theoretically qualify for the express train, but the department’s computer system says otherwise. This begins a chain of events that separates the duo and sends Manny through the underworld, as he attempts to piece together the mystery, escort Menche to her proper destination… and just maybe find redemption for himself. The story takes place over the course of four years, essentially breaking the game into four acts. It begins in the city of El Marrow, before moving to the forlorn city of Rubacava, to a factory at the edge of the world, and finally back to the big city.

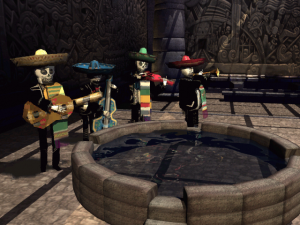

Beyond its take on metaphysical concepts, Grim Fandango also has a uniquely appealing visual style. It’s patterned after the film noir stylings of the ’50s, with art deco architecture and a classy jazz soundtrack. Since the characters are all dead, technically, they are designed to look like Mexican calaca figures, skeletons used in the Day of the Dead festival. The land of living is only briefly visited, but is represented by a Richard Hamilton-style collage. The underworld denizens cannot be killed by most regular means, but the most popular method of murder is known as “sprouting”, wherein a victim is shot with a special dart that causes flowers to grow out of their bones. It also gives new meaning to the term “pushing up daisies”, a fact which does not go unmissed by Manny.

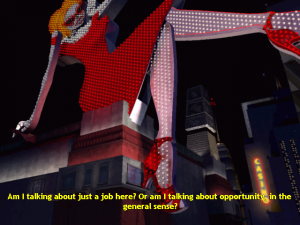

Grim Fandango is also the first LucasArts adventure game to utilize 3D. The backgrounds are all static prerendered bitmaps, with the characters consisting of polygons. While technology was quite limited back in the late ’90s, the stylized look of the character designs are geometrically simple enough to be rendered effectively, making it much more appealing than similar games of the era (including its own successor, Escape from Monkey Island, which uses the same engine). While the software graphics mode uses some pixellated textures, the hardware accelerated options clean them up, as long as your video card doesn’t choke on it.

While the transition to 3D is handled smoothly, the new interface, at least in the initial 2000 release, proves something of an issue. The familiar point-and-click interface is completely gone, and instead you control Manny directly, with either the keyboard or a gamepad. You can choose from character relative controls (similar to Resident Evil, also known as “tank controls”), where you turn by pressing left or right and press up to move forward, or camera relative, where up is always up. Neither really works though, because Manny is way too slippery around corners. Each of the three commands (“Look”, “Use/Talk”, “Take”) are mapped to various keys. If something catches Manny’s eyes, he’ll turn his head, but it’s not always clear which bit of scenery he’s looking at until you inspect it. It makes finding hotspots extremely difficult, requiring that you comb every edge of every screen to look for stuff. The puzzles themselves, save for one bit where you need to decode some abstract clues to forge a betting ticket, aren’t really more difficult than standard LucasArts’ fare, but this set up makes it extremely easy to miss vital items, and thus impede progress.

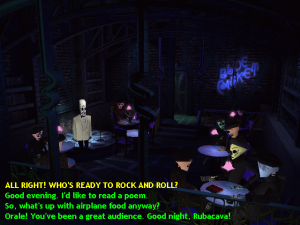

In a lesser title, these issues would almost be game breaking, but the rest of Grim Fandango more than makes up for it. At the core of it is, of course, Manny. Like many other LucasArts’ heroes, Manny is something of a wisecracker, offering wry observations while being able to handle his dire situation with admirable aplomb. Most of the best lines from his commentary – try picking up something in the gigantic box of cat litter, and he’ll just laugh at you. “Ah, my bread and butter,” he says of his casino patrons. “Thrill-seeking rich folk with a poor grasp of statistics and probability.” At open mic night at a beatnik club, you can get in front of the crowd and form some pretentious nonsense poetry from a series of randomly generated phrases.

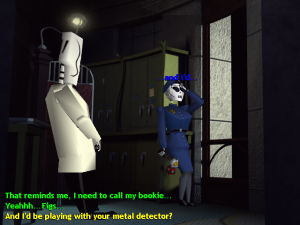

One halfway brilliant scene involves Manny trying to obtain a metal detector from Carla, a security guard. She begins a long and rambling sob story about her time as the living, and Manny’s dialogue responses constantly change as the tale of woe progresses. The first two options are ineffectual, although they grow amusing as the situation becomes awkward. The third option involves asking about the metal detector, and the responses slowly grow less subtle as Manny begins to lose his patience. (“I like short-haired cats.” “You know what I like? METAL DETECTORS!” or “People think I’m stuck up sometimes, believe it or not.” “Why? Because you wouldn’t let them touch your metal detector?”)

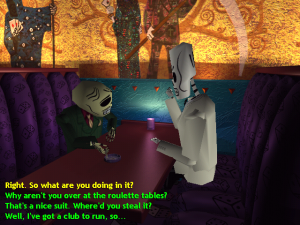

However, while Guybrush Threepwood and Sam & Max rarely go beyond the roles of amusing cartoon caricatures, there’s something, ironically, more human about Manny. He has astounding ambitions – in the transition between the first and second chapter, he takes a crappy little diner and transforms it into a swinging nightclub. Between the second and third chapter, he sneaks himself onboard a ship and works his way all the way up to captain. Like any good film noir hero, though, he’s something of an underdog – he’s outpaced by Domino at his salesman job, his casino plays second fiddle to the big-time mobsters in Rubacava, and his ship captain job is quickly ended when he’s attacked by corrupt customs officials.

He is nothing if not persistent. He’s not even sure why he’s embarked on this adventure. Does he just want the high commission for escorting Menche? Does he truly feel guilty for abandoning her? Or is he, as one character suggests, in love with her? Manny is practically batting off the women like flies in Rubacava, but none of them mean anything to him beyond some flirtatious banter. And like Rick Blaine in Casablanca, it’s never spelled out exactly what Manny did that got him stuck in his position – not many of them like to talk about the “fat days”, but it’s implied to have been pretty bad.

Through Manny’s many internal conflicts, he manages to keep his cool. His voice is provided by Tony Plana (who would later become known as Betty’s father in the American version of the sitcom Ugly Betty), and the dialogue is read with an appropriate world-weariness. And there are no dramatic monologues, nor ham-handed self-proclamations. It’s quite subtle compared to most video game writing, which again puts Grim Fandango in a class of its own.

Manny’s constant companion is Glottis, a demon. Demons are not human souls, but are rather manufactured by the rulers of the underworld to perform various menial tasks. Glottis’ job is to fix cars, although he also has a thing for turning them into ludicrously detailed hot rods. He looks like a monstrously oversized teddy bear, and would be scary if not for his goofy, expressive eyes, and tiny ears that flutter enthusiastically. Like Manny, he faces his own crisis of conscience when stuck in Rubacava – since there are no cars and therefore no need for a mechanic, he becomes a pianist for the club. But his penchant for booze overwhelms him, which would be depressing if his slurred one-liners weren’t so hilarious. It’s tragic, then – he was made for the sole purpose of fixing stuff, but he can’t, and it makes him miserable.

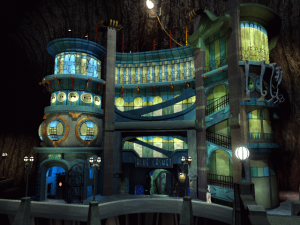

While it’s really the characters that drive Grim Fandango, the world design deserves a special commendation. Like Tim Schafer’s other games, it’s filled with random bits of silliness, like the flaming beavers that guard the Petrified Forest, or Glottis’ vehicle, the Bonewagon, which is eventually given ridiculous hydraulic lifts. The underworld isn’t always the happiest of places, obviously, but it does contain one of the most entrancing locales ever seen in a computer game – the city of Rubacava, which is the center of the game’s second act.

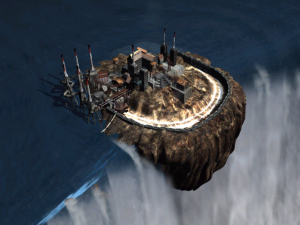

Apparently most of the lesser souls aren’t able to fully complete the journey to the underworld, and instead start a new life for themselves. Rubacava is filled with such drifters, those who have given up on their goals and are instead content to drink and gamble their troubles away for the rest of eternity. Like Las Vegas in the night, the neon lights brighten the darkness, and the place would be gorgeous if it weren’t run by shifty mobsters and crooked cops. Manny fits in right along with these denizens, having opened up a casino to whittle away the days while he waits for Menche. Alas, Rubacava is such an amazing locale that the rest of the game really just can’t measure up to it. The third chapter sees Manny stuck in an island prison solving a bunch of boring mechanical puzzles. And while the forth chapter provides a satisfying conclusion, it never quite replicates neither the humor nor the despair of the earlier acts.

There are dozens of ways you can praise Grim Fandango, from its unforgettable locales to its vulnerable cast of characters to its spot-on dialogue. But the biggest compliment you can pay it is that there’s nothing else fully like it, especially compared to other adventure games. Gabriel Knight may have a fantastic story, but when placed against dozens of other supernatural murder mysteries, it doesn’t really differentiate. The same can be said about The Longest Journey – also extremely well written, but it blends in together with numerous other works of fantasy fiction. If Grim Fandango was a book, or a comic, or a movie, it would still stand out as being entirely unlike anything else in the medium. It would probably still go underappreciated, of course – it’s hard to adequately describe its intricacies in a way that’s easily understood, which may have contributed to its disappointing retail performance. While not technically LucasArts’ last adventure game, it’s the point where it seemed like the adventure game genre had died. If viewed from that perspective, then Grim Fandango is the most beautiful swan song imaginable.

Grim Fandango was developed primarily for Windows 98 PCs, so trying to run it out of the box might prove to be troublesome. It is, however, easily playable on modern platforms using ResidualVM, an interpreter similar to SCUMMVM.

Preferable to the original release is Grim Fandango Remastered, released in 2015 on digital download platforms. It was ported and published by Double Fine, and like many of the other LucasArts games that involved Tim Schafer that received similar updates. In addition to making it compatibility with modern computers (and porting it to the PlayStation 4, Vita, and mobile platforms), it has a number of small tweaks and additions.

It’s not a complete remake, since it still relies on most of the assets from the original game. As such, the gameplay window is still displayed in 4:3, with an option to stretch to widescreen. The backgrounds are no longer confined to the 256 color limit of display cards at the time, but since they were originally designed for 640×480 resolution, there’s only so good it can look. There’s an option for improved character models though, along with enhanced lighting that shades the characters based on where they’re standing in a given room. It might not seem like much but it subtly enhances the look of the game. Also included are higher quality music and voices, better looking (less compressed) video, and a director’s commentary mode.

But the most welcome improvement is the addition of a proper point-and-click interface, using the same verb coin found in Full Throttle and Secret of Monkey Island. Inventory management is still a little clunky but it still makes navigating around the world much, much easier than before. There’s still an option for the old interface (and old graphics) if you’d prefer to play it like that – there’s even a trophy/achievement for doing so – but it also works to fix the only one big flaw the original game had.