Horror was once a rare gaming genre, with little variety, typified by the gameplay styles of Resident Evil and Silent Hill. With the rise of the indie scene, we suddenly saw a massive increase in horror games, such as Five Nights at Freddy’s, Choo Choo Charles, and Poppy Playtime, which took the gameplay and themes in different directions. While horror was seen primarily as an adult-oriented genre, some of these indie horror games became popular with kids.

In 2019, Tequila Works, the Spanish developer of such games as Deadlight and Rime, released a horror game that was not only more accessible to families but actually stars a kid, has a Pixar-esque art style and is focused on psychological horror more along the lines of Silent Hill, rather than focusing on jump scares. And they released it… as an exclusive on Google Stadia, Google’s failed experiment of a game-streaming service. (Google even had a deal where people who paid for Stadia Pro could get Gylt as a pack-in game.) In 2023, after the fall of Stadia, Gylt managed to break out and make its way to PlayStation, Xbox and the PC, followed by a Switch release in 2024.

So, what is Gylt? Besides a respelling of the word “guilt?” Or, according to some websites, an acronym for “get your life together?”

The game opens with a disclaimer, saying that it contains depictions of bullying, and if you need help, to contact a professional. Other games that use horror as metaphor for real world issues, such as The Missing: J. J. Macfield and the Island of Memories, have disclaimers as well, but a warning about depictions of bullying is pretty new.

The story opens in the fictional town of Bethelwood, Maine, where a young girl named Sally Kauffman is putting up missing posters for her seven-year-old cousin, Emily. Sally narrates that after Emily disappeared, the town gave up looking for her after a few weeks. Soon after, Sally is accosted by bullies, who taunt her and chase her up a snowy mountain far away from her town.

She meets an old man who runs a cable car, who soon disappears. She takes the cable car through some kind of apparent dimensional shift, and ends up in a very ruined, broken-down and twisted looking version of her town. People are nowhere to be seen, and it isn’t long before Sally discovers the town is crawling with monsters.

Sally starts out defenseless against the monsters, but eventually gains ways of fighting back, such as firing a powerful beam from her flashlight to destroy bulbous pustules on the monsters’ bodies. They can also be distracted by throwing soda cans that can be obtained infinitely from vending machines. You can one-shot them with a behind-the-back stealth kill with your flashlight, though it eats up one-third of your flashlight battery and if overused, can leave you in real danger. Naturally, there are batteries lying around to refill your flashlight. There are also inhalers to restore your health, indicating that perhaps Sally has asthma, which might also explain why she can only run for about three seconds before having to recover.

As is often the case in games like this, avoiding combat is often the best idea, though more skilled players can defeat enemies easily. The game is designed to encourage stealth. Many enemies are much faster than you are, with such abilities as very fast lunging attacks, shooting out goop from a distance, teleporting, firing off screams which cause headaches that disable your defenses, or even trying to suck out your soul. Enemies can easily swarm you in groups and make quick work of you if a bunch of them are triggered at one time. Fighting one at a time isn’t so bad if you can figure out how to target their pustules and dodge their quick charges, but there are situations where groups of three or four enemies show up, and you really don’t want them to be all alert at once.

Stealth very much is the name of the game here. The controls are built around making stealthy movement quick and easy to control. Sally controls very smoothly for a horror protagonist, almost like controlling a platformer protagonist who just happens to be unable to jump. The camera can be freely moved, and there’s even a button toggle for shifting Sally’s onscreen position to the left or right of the camera, to make it easier to see around corners.

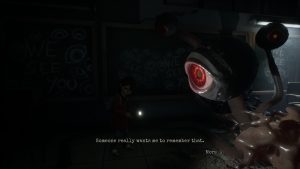

The enemies themselves come in a few varieties which force you to change up tactics for dealing with them. One particularly nasty enemy is invisible, can only be seen via its footprints and occasional slight blinking into visible existence, always knows where you are even if you’re hiding, can open doors, and repeatedly returns to life when killed. Another enemy can’t be killed at all, but can be frozen with the fire extinguisher for only a few seconds.

There are also moments where the game mixes things up a few ways. There are puzzles of the usual sort expected in this genre, of the ladder-pushing, valve-turning, etc. variety, some of which involve the use of your flashlight or fire extinguisher. There are sequences where an enemy will suddenly burst into the room right after you collected something important. There are scripted scares. And of course, there are boss fights.

Now, with this being a horror game, let’s take a closer look at the story and presentation. As the game’s disclaimer hints, much of it has to do with bullying, but there’s also many other aspects to the story as well, including supernatural elements and lore. But let’s start with the bullying, because it’s a major part of the story, and no discussion of Gylt would be complete without talking about it.

As you explore the school in the twisted town, it’s not long before you see a group of mannequins arranged to act out a scene in which one is wearing a bucket on its head labeled “PATHETIC” while three others are standing around and pointing. Not exactly subtle. There are walls, bathroom stalls, and other things marked with elementary school insults, such as “Loser,” “Smelly,” “Poop head,” “We’ll be happy when you’re gone,” “You’ll never be one of us,” “Stop trying to be our friend,” and many more.

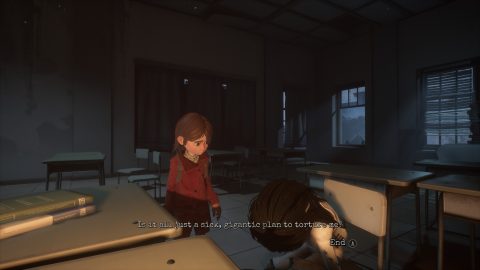

But the bullying imagery really ramps up when you arrive at a theater, and you hear Emily’s harrowing crying and wailing, “Make it stop!” “Leave me alone!” acted out with impressively good and emotive voice acting. This is made even more disturbing by the fact that her cries of sadness and pain continue while you try to figure out how to reach her. And when you do reach the auditorium, what you see is even worse.

Emily is in the middle of the theater, strung up against her will, while multiple spotlights shine on her, as a movie plays on the screen, showing various sad moments from her life. Such as the apparent death of her grandfather. And what appears to be Emily reaching out to Sally for support while Sally gets annoyed as other kids, portrayed in a monstrous fashion, mock her. This torment, along with Emily’s loud crying and screaming, continues the whole time while you have to disable the spotlights shining on Emily while dodging another spotlight that can drain you of health. This is actually one of the game’s boss fights.

Figuring out what’s going on in the main story isn’t too hard, as the backstory behind Sally and Emily is told through a combination of symbolism, journal entries, and spoken dialog. Emily was being bullied severely shortly after starting school, and would run to Sally for help, but Sally, preferring to spend time with her own friends, would push Emily away rather than serve as a source of support. Teachers did nothing to help, and the bullying even got physical during gym class, with the gym teacher ignoring it. You could say Sally is feeling, well, guilt over her unwillingness to help.

While it does seem like the town has it out for Sally and Emily, they aren’t the only ones suffering.

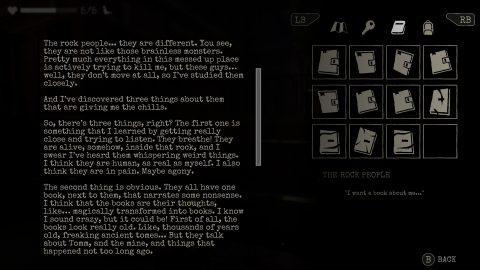

Throughout the game, you encounter journal entries, as well as people who’ve been turned to stone, all of whom appear to have worked for the corrupt mining company, Tomm. While journal entries are a super common cliche in horror games (Tormented Souls in particular relied heavily on them to tell its backstory, which raised questions about why some of these characters even bothered to keep such meticulous and erudite journals), here, not only are they actually written at the education level one might expect from each person, there’s also an explanation provided by one of the journals. They appear to be the crystallized thoughts of various people, having been changed into journal form without the person having actually written anything. Some of them being the person’s thoughts shortly before whatever happened to them.

The statues sound like they’re breathing or whispering. Using a magic red stone known as a blood quartz breaks the statues and seemingly frees whoever is inside, possibly to the afterlife, as they simply dissolve away.

Oh, and when Sally dies in this game? She turns to stone herself. The same horrifying fate that has already befallen many other townspeople. Another journal entry indicates that the game’s monsters are also transformed townspeople.

The bullying imagery is meant to hit players on an emotional, gut-punch level, but the rest of the story is horror meant to hit on a disturbing and scary level. People being turned to stone while still being seemingly alive or conscious is a fate worse than death, but a lot of media is loath to portray a child being killed, so Sally experiences something arguably more horrible.

The journal entries also provide a lot of backstory on the town, on the company that practically owns it, and on the people who’ve been turned to stone. Some things are explained, while other mysteries are left unanswered. We see the thoughts of soldiers, mental health professionals, random citizens, and even Emily herself, all in these magic journal entries that provide physical form to what was in these people’s heads, while also either hinting at or spelling out backstory. Some of the entries even show people speculating on the nature of the town itself and its mines, the nature of the journal entries, and more. There’s a lot more going on in this town than just Emily and Sally’s story, as the town itself, and its old mine, hide many secrets.

There are also a handful of completely black paintings that change into paintings showing scenes from Emily’s life if you shine your light at them, providing a bit more backstory.

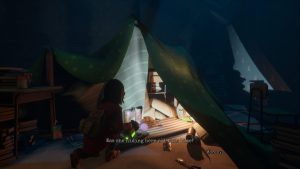

The game’s story is ultimately told through a combination of spoken dialog, journal entries, and environmental storytelling. Visual clues can hint at what was going on, such as the juice boxes, boxes of cookies and chocolate-bar wrappers found in the vents. Do they mean Emily was hiding there in terror, storing junk food for sustenance? That would explain why her fingers and clothes have what appears to be mud or maybe chocolate on them. A tent with magazines and food in one of the school’s rooms leads Sally to speculate that this might have been a place where Emily hid out to escape her tormentors, or the monsters.

Sally has a lot of personality. She has several nervous idle animations such as tapping on her flashlight. And she has a lot to say. She speaks out loud and gives her thoughts and opinions on things that she sees, both important things happening in the story, or even environmental details. She wonders why her school has a canary for a sports mascot, thinks that having to learn about her town’s mining history in school is stupid, and even speculates if someone is using Emily to bait her into a trap. Sally even sometimes says out loud what the player might be thinking, like complaining, “Come on! Stay down already!” during a boss fight or getting frustrated at the mere existence of invisible monsters.

She acts very much like the kid that she is. Which is notable, considering there are other games that fail to portray kids who act their age at all – a particularly egregious example being Alba: A Wildlife Adventure, which implies its protagonist is eleven or ten, but has her act more like she’s four. Sally comes across as more believably her age of eleven, not wise beyond her years but not excessively childish either, speculating on what some of the things she sees could possibly mean, and understandably being a bit distrustful of adults despite knowing she might need to rely on their help.

Indeed, Sally’s emotional maturity level plays a big role in the game’s three endings. Because depending on what ending you choose, she does one of the most horrible things a desperate, scared child can possibly do, or one of the most selfless things a terrified child with an overpowering guilty conscience can do, and pays the ultimate price. Is there a third ending which is actually happy? Yes, and you need to work to earn it, by freeing all the people who’ve been turned to stone. Then, a new choice becomes available which allows you to sidestep the need for a sacrifice and receive a true happy ending.

The ending, like most of the game’s cutscenes with spoken dialog, is told through a series of drawings, possibly to save on budget and avoid the complication of lip-syncing dialog across the five spoken languages the game was dubbed into. Indeed, this is a mid-budget game. The production values are otherwise pretty good, with quality voice acting from a small number of actors who show a range of emotions, movie-like music, smooth animation and a lot of environmental detail.

The difficulty is easily on the low side for survival horror and stealth game veterans. Enemies can be brutal in groups but are pretty easy to sneak past when patrolling. While conserving ammo is a must in many horror games, if you can individually stealth-kill enemies that patrol in groups and take out the rest with your flashlight, you can remove nearly every killable enemy in the game. You can turn off auto-aim for the flashlight beam, but there’s no other way to raise or lower difficulty. Some of the collectibles are pretty tricky to find.

Gylt might be a kid-friendly horror game, but it is still a horror game with a creepy atmosphere, lore with unanswered questions, its share of scripted scares, and it’s more of an all-ages experience that adult gamers could be able to appreciate. It even arguably takes inspiration from Stephen King, with its Maine setting, use of bullies, missing posters and an alternate world, while containing a shout-out in the form of Bachman School referencing King’s former pen name.

It might not overtly show death, but it opts to show fates far worse than death. It’s not afraid to really pound home how bad bullying is, the moral cowardice of bystanders who do nothing, and how people can be in denial about how bad their own behavior was. While another horror game, Rule of Rose, featured elementary school bullying as a major story theme, it treated it as largely window dressing without delving into it in any serious way. Gylt actually tackles it in a mature, real world way, and did so before Silent Hill: The Short Message tried its hand at tackling teen issues. And the game’s bad endings pull no punches.

The only other thing parents might want to know about before deciding if this is something they’d buy for their kid, is the use of occasional profanity – “damn,” “hell,” and “goddamn” are all used in a few journal entries, but no profanity is spoken aloud by any character. There’s also what appears to be faint blood dripping from certain things in two scares.

At a time in which the indie scene is giving us many horror games, and many games that have something to say, Gylt is both at once, while also being family-friendly-ish. It might be worth checking out for someone who is interested in seeing how these two things come together, or someone who’d like to see one of the rare kid protagonists in horror, or just wants something a little different from the horror genre. Or, it could be a good gift for a kid who’s interested in experiencing a different kind of horror game. They might even learn a valuable lesson from the main narrative. Some have criticized it for being unsubtle, but that also means it’s crystal-clear, and that could be a very good thing, especially for kids.