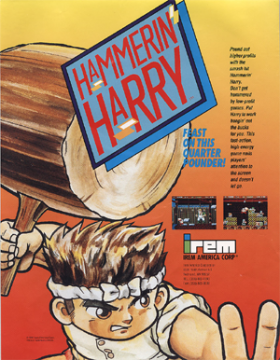

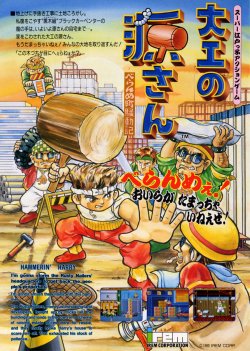

Ah, the days of mascot platformers. Hammerin’ Harry – known in its Japanese homeland as Daiku no Gen-san, or” Gen the Carpenter” – begin as an arcade game by Irem that soon spun off into several different incarnations. The real star of the game, of course, is the hero’s gigantic hammer, which, in addition to pounding enemies into submission, also has a number of various uses, which different from game to game.

In many ways, Hammerin’ Harry is sort of like a modern day version of Mystical Ninja / Goemon – both involve slightly absurd renditions of Japanese society, although Harry has a bit less mysticism. It’s no wonder that the series rarely saw light in the USA, perhaps coming off as “too foreign”. Although the first games in the series keep to fairly realistic settings, later games go all crazy and have Harry fighting ghosts or sending him into outer space. After retiring from the world of video games, he began starring in a number of pachinko games, before leading to his resurgence as the star of a 2008 PSP game.

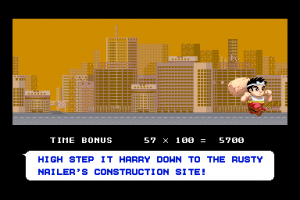

Hammerin’ Harry begins with the Rusty Nail Construction Company demolishing Harry’s home. (Why, exactly? Well… hmmm.) He sets off to exact retribution with his sole remaining possession – a gigantic hammer. In addition to whacking things, you can use the hammer as a shield by ducking, or smash the ground with it, causing a minor earthquake which can stun most enemies on the screen. Each stage is usually littered with objects – boxes, bricks, etc – which can be whacked and sent flying across the screen, damaging enemies in the process. There’s one part where you can hit a mountain of pipes, which then roll across the screen, fall in the water, and act as platforms to continue. None of this is scripted either – it’s a very cool early implementation of physics.

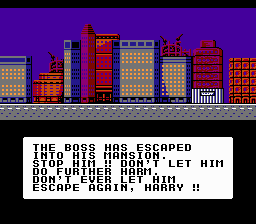

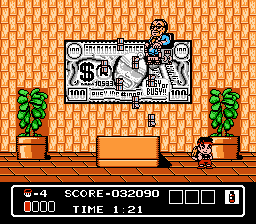

Like many arcade games of old, particularly ones from Irem, Harry can only take a single hit before dying, sending him back to the most recent checkpoint. It’s tough, but not as tough as earlier Irem titles like Ninja Spirit or Legend of Hero Tonma. And thankfully, unlike, say, R-Type, the checkpoints are reasonably close together, so you’re rarely sent back more than a few screens. You’ll occasionally find power-ups, like helmets, which can absorb a single hit; chili peppers, which allow you to swing your hammer in a circle; and POW icons, which grant you an extra big ass hammer. The game’s only six stages long, and while there are plenty of cheap hits, it manages to be challenging without being extraordinary frustrating. The final boss is against a greedy little business who flies around in a hovering wheelchair and attacks by throwing deadly dollar bills. There’s some kind of message about the evils of greed in here somewhere, but damned if anyone can figure it out.

The graphics are vintage Irem, with excellent spritework, large, expressive characters, and detailed environments. The theme song is catchy, if not particularly classic. It features a number of voice samples which are simultaneously hilarious and annoying. At the beginning of each new life, a disembodied voice yells “IKUZE!” in Japanese, or “LET’S GET BUSY!” in English. Harry yells “Teyandei!” whenever he gets hit, or, more simply, “OUCH!” in English. There’s even a “Hammer Time!” voice sample of suspicious legality. This goofy little yells have since become a trademark of the series. Each stage also have silly names, like “Needless Markup Maul”, and some of the cinema text is equally as goofy.

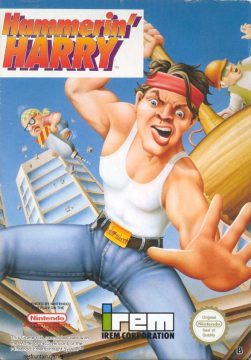

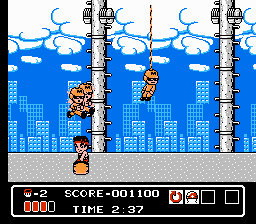

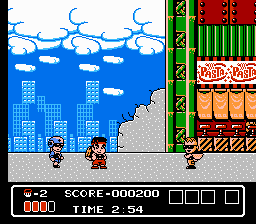

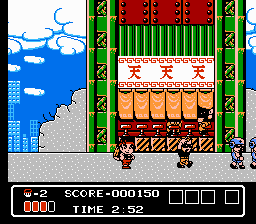

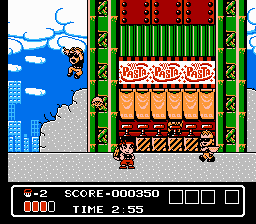

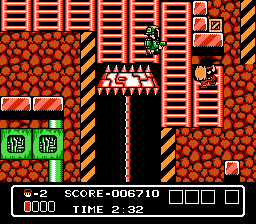

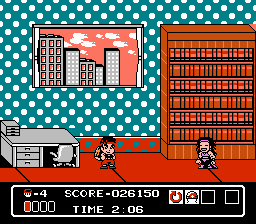

Hammerin’ Harry was also released for the Famicom, and for the NES in Europe. On the surface, it’s a pretty good translation – the action is fast, the controls are right, the graphics are decent, and it even manages to keep the voice samples. You can also take three hits before getting killed, making it significantly easier. However, apparently the old 8-bit system couldn’t handle the simple physics of the arcade game – there are still a few boxes lying around, which hold power-ups, but you can’t fling them across the screen anymore. As a result, the stages seem a little bit barren in comparison. Many of the levels have been changed around too, as have most of the boss fights. You can still hit enemy projectiles back at the bosses, at least. There are also whack-a-mole style bonus games after each level.

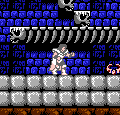

There are only five levels rather than six, and many segments from the arcade game have been cut out, replaced or rearranged. The second construction site stage and underground stage (forth and fifth in the arcade) have been entirely removed, but there’s a brand new level at the end that takes place in a mansion, and an additional segment where you’re on a boat out at sea. There’s also a cool segment added where you’re about to confront the final boss, and the seemingly innocuous secretary jumps into the room, transforms herself into some kind of 80s music video star, and proceeds to karate kick your sorry butt.

The European NES version is best remember for the cover, where the artist seemingly tried to draw the hero with an exaggerated angry face but instead ended up with something that looked like Sloth from The Goonies. This version also removes some of the Japanese symbols and replaces them with other logos. Like many of these Euro-exclusive NES games, it’s become quite expensive on the aftermarket, though the Famicom version is not all that pricey.

Screenshot Comparisons