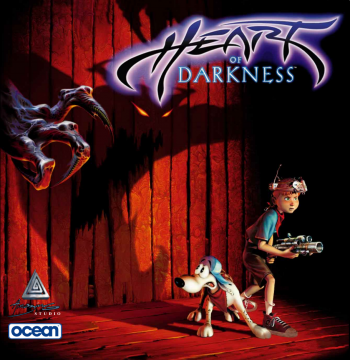

Éric Chahi is probably best known for his masterpiece Another World (or Out of This World, as it’s known in North America). Heavily inspired by Jordan Mechner’s Prince of Persia, they both helped define what’s known as the “cinematic platformer“: screen-flipping instead of scrolling, no life bar, no leaping thirty stories high, and no jumping on an enemy’s head. Made by the same Éric Chahi (among others), Heart of Darkness also ticks all of the appropriate tropes of the same genre, but is unfortunately not as widely known as its more famous predecessor. (It also has absolutely nothing to do with the Joseph Conrad novella of the same name.)

The game’s hero is Andy, a boy who seems to only have one friend: his dog Whisky. He’s a bit of a shut-in and lacking any real friends, but he’s also something of a genius, having fashioned a functioning “plasma rifle” out of an old flashlight, a colander, and random bits of scrap metal. He’s even built his own computer, complete with a custom OS, and constructed a flying machine made from God knows what.

The game begins with a cutscene with Andy stuck at school, daydreaming. His teacher, apparently an expert in psychological torture, decides to lock him in a dark closet, knowing perfectly well that Andy is mortified of the dark. But thankfully, the bell rings just before Andy is trapped inside, and he makes his escape. While fleeing, the teacher yells that pupils are required to observe the solar eclipse that will occur the same afternoon. So Andy, being a curious child, goes to the park with his dog to watch the eclipse. Then, somehow, in the dark, Whisky is taken away, leaving nothing behind but the baseball cap that he and Andy share. Andy then does what any child prodigy would do: he runs into his treehouse/fortress of solitude, where all his futuristic equipment is stashed, grabs his plasma rifle and zooms off in his flying machine to rescue his pet. He soars through the clouds, discovering a completely foreign world, where he soon collides with a black winged creature, which causes him to crash into a cliff. Andy now has to continue by foot, and that is where the game truly begins.

It’s interesting how there’s also a sort of similarity between the main elements of Another World and Heart of Darkness, apart from gameplay. In both games, the protagonist is the solitary type (Heart of Darkness’ hero does not seem to have any friends apart from his dog and the scientist in Another World works at night, alone), but is also apparently very knowledgeable about sciences, and is whisked away to another reality where he befriends an alien that helps him in his quest. Said reality is also filled with numerous nasty creatures which want nothing more to kill him.

In the first level of Heart of Darkness, you have to get used to the controls and the enemies’ behavior, but technically it’s not all that difficult. The game being mostly linear, you almost never have to wander around and very rarely have to backtrack. After a few screens you’ll encounter the most common enemies, in the form of shadow creatures. There are plenty of them, but your plasma rifle will allow you to dispatch them quickly. All they can do is run or fly towards you (by flapping their arms) and most of them will just harmlessly grab you. You can then shake them off by moving left and right with the right timing. Some of them will eat you in one bite, though. You also have to get acquainted with the controls and perform some double somersaults early on, the game’s only concession in terms of realistic moves for a young child. Failure to master said jumps will send you careening into a chasm, introducing you to one of the many, many deaths you will experience throughout the game.

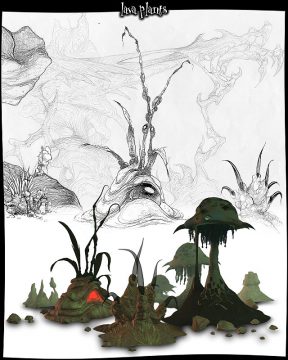

At the end of this first stage, you are confronted with an enormous monster that snatches your rifle from your hands and swallows it whole. There’s nothing you can do about it and there is no way to fight the monster, so if you don’t run away quickly, you’ll be treated to another rather nasty death scene. You are therefore left defenseless against your enemies, thus allowing them to eat you, disembowel you, or snap your spine in two, among other ways you can die. Indeed, and despite the apparent cheerfulness of the ensemble, the deaths will always come as a harsh reminder of the fragility of a schoolboy’s body, be it thanks to the enemies or the environment: water is often off-limits, filled with carnivorous animals, plants will try to chomp on you, lava will fry you, boulders crush you, and so forth. Without your weapon, your only means of defeating the shadows is, of course, the light. But light is also a very rare occurrence in this world of darkness.

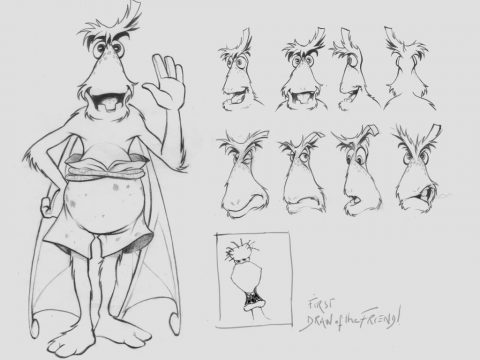

After a while spent at escaping death, you encounter a winged creature which turns out to be a kind of gentle idiot, called the “amigo”, and wants to take you to its village. But before the two of you can get to safety, you are attacked by winged shadows (they have the ability to throw fireballs), and the amigo accidentally drops you into a lake. At the bottom of this lake is a green glowing meteorite. After you’ve touched it, you realise you can shoot green energy out of your hands. This provides you with a means of destroying shadows again, and also allows you to make seeds instantly grow into trees you can climb to reach higher places. The seeds can also be moved and can float on water, allowing you to create trees in hard-to-reach places in order to progress, adding a bit of puzzle-solving to the game.

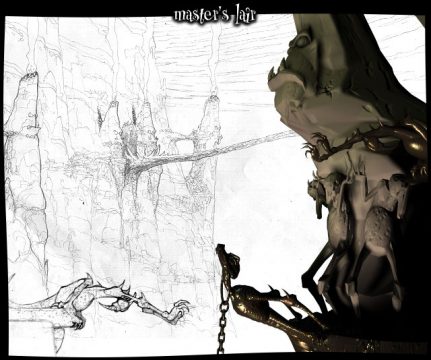

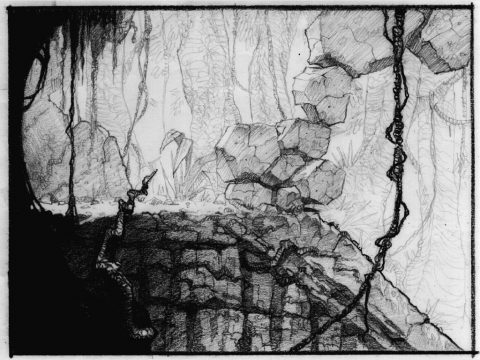

After all this, Andy has to make his way through lava-flooded caves and finally make it so the amigos can touch the magic stone themselves, allowing them to fight alongside you against the winged shadows when you lead them in a final assault on the master of darkness’ fortress. Inside the fortress you reunite with your dog, but also with your plasma-rifle after being swallowed whole by the same monster that stole it from you at the beginning of the game. You then use it to threaten the master’s pink slimy (in all senses of the word) servant into telling you of a way to defeat the master. He is quick to provide you with one – you must rebuild the meteorite and throw in the heart of darkness, the black hole-like thing that is apparently important. So you begin your search for the three missing pieces of the meteorite, battling a few monsters on the way, but mostly dealing with very light puzzles. Once you have brought what you and the servant think is the last bit, the servant realizes that one final piece is still sitting on the bridge above the heart of darkness, and you have to go retrieve it if you want to finally defeat the master. So down you go, and that is where you finally combat the main villain (whom, by the way, bears a striking resemblance to Andy’s teacher).

This battle, although it is the climax of your adventure, is rather underwhelming. You do not fight the master himself, but rather more of his minions, and you have to battle your way to the end of the bridge by cutting through a seemingly never-ending influx of enemies. Every now and then, the master of darkness will throw a couple of fireballs a you, which can only be avoided by timing your double jumps carefully, which shouldn’t be too much of a problem at this point in the game. You finally reach the final piece of the meteorite, and the amigos, who made their way into the fortress somehow, lower the meteorite next to the bridge, crushing the servant in the process. You jump onto the meteorite to place the last element, it then falls into the heart of darkness, followed by the master who does not fall before taking you with him.

While effectively defeating the end boss could mean the end of the game, there is still one “level”, of sorts, to beat. Here you won’t be able to fire your plasma rifle, you will be surrounded by complete darkness, and the only enemy will be something that must be either the disembodied master of darkness, or the very concept of darkness. All you can do to defeat “it” is to bludgeon it with your weapon and avoid its attacks. After a short time,a ray of light will appear, and it turns out that this ray of light comes from… the door to your tree house that your mother just opened. You were apparently in the dark, alone, fighting your own fear, and all of this was in your head. Your dog is there too, and seems as happy as ever to see you. Although this appears to be one of these rather uninspired “it was all just a dream” ending, it’s actually negated later in the same cutscene where we see the amigos playing with the remains of Andy’s flying machine and torturing the servant. So it was a dream, but it wasn’t. Confusing.

Each time you beat a level, you can watch the corresponding cutscene(s) again from the main menu, and the last one is no exception, but goes one step further. This one is available in 3D and the game was sold with a pair of blue/red glasses to allow you to fully enjoy it.

All in all, Heart of Darkness is a lot of fun to play. The controls are responsive and the gameplay is simple yet engaging. You do spend a lot of time restarting certain screens, trying to finally get over a particularly difficult part, but the automatic save system allows you to pick up just at the screen you died or in some cases just a few screens before. The levels are populated with just enough enemies and platforming elements (often both at the same time) to keep things interesting, although the game is quite short.

The sound design is also extremely well done. During actual gameplay, there is no music at all, only the noises Andy makes by walking, jumping, and other actions. You can hear him pant and puff as he runs, jumps, and grabs onto ledges, gasp as he falls down and prepares for the landing, plus all the enemies’ noises and cries, which all makes for a very lively experience. Plus, all the sound effects were recorded by a foley artist, using the same methods as in films. The actual music is only to be found in the cutscenes, and, while there are plenty of them, one can’t help but feel that it is a wasted potential, considering the quality of said music. Most of it is drowned out by dialogue or sound effects, which is a pity.

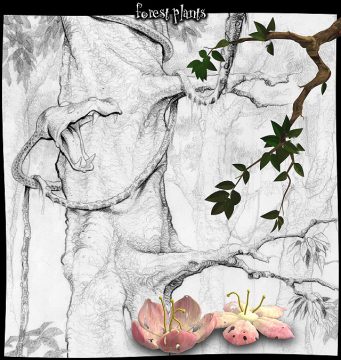

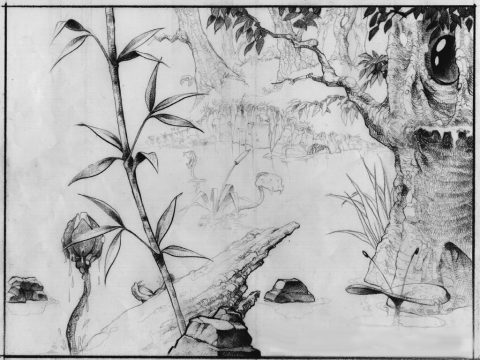

The animation is on par with the rest. Even though the sprites are very pixelated, and already were at the time of release, everything is bright and colorful, and not only are the hero and enemies carefully animated, but so are the backgrounds, full of innumerable details, like reeds under water, rocks falling, plants swaying in the wind, and red eyes blinking. This lends a particular feel to the game, and makes every screen look busy and feel alive. Being involved with textures, lighting and level design, Éric Chahi conceived each screen like a painting – the textures were drawn with the idea of how they would fit together on each screen, and the lights were used to emphasize or attenuate forms and shapes, creating specific moods.

Gameplay-wise there is one mechanic which should be used more often, and that is the use of shadows. In one instance, in order to push an unreachable boulder, you have to push its shadow with your own, thus pushing the boulder itself. There are also a few situations where an object’s shadow will come to life and maybe kill you if you’re not careful or don’t destroy the shadow’s source. This use of shadows is unfortunately very rare, when it could have been much better integrated, seeing how the whole endeavour takes place in a world of living shadows. The long and frequent cutscenes are also a problem. The game’s promotion material proudly claims that the game has “more than 30 minutes” of movies, but that may actually play against it more than in its favour. Despite the story’s weakness, the numerous cutscenes don’t really help the player understand what’s going on, and are more of an interference than a welcome interruption. As Éric Chahi himself said, he is not a fan of cutscenes. He praised those in Heart of Darkness for their beauty, but he thought they were too long and weakened interactivity, which should stay the main focus of video games, as opposed to cinema.

Heart of Darkness had an extremely protracted development cycle. After the international success of Another World, Éric Chahi was asked to join a new little development venture, “Amazing Studio”, to work on its first (and unfortunately only) production: Heart of Darkness. The initial team was composed of like-minded gentlemen who, like Chahi, had been working in the video-game industry for quite some time: Frédéric Savoir and Fabrice Visserot, who had previously worked on Flashback (often thought of as the spiritual successor to Another World); Daniel Morais, who had worked for “Chip”, the publisher of Chahi’s games prior to Another World, and had worked on the PC version of that very game; and finally Christian Robert, who did most of the 2D art of Heart of Darkness, including character design, backgrounds and animation sprites. (Robert unfortunately passed away in 2010, and all the artwork at the end of this article is from him.) Éric Chahi himself worked on the textures and lighting but did not participate in the programming as he had previously done in his solo projects. He later stated in different interviews that this may have been a mistake and that some problems existed within the creative team, though these were never elaborated on.

Development on the game proper started in 1992, and all the fans of Another World waited with bated breath for Chahi’s next game. But this took time. A long, long time. After several months, rumors began circulating about the game’s cancellation. Amazing Studio kept mostly silent throughout the development, thus fueling tons of crazy speculation. But finally, in 1995, the game was unveiled at the Los Angeles CES. It was just one pre-rendered teaser, but it made a very good impression. Famed movie director Steven Spielberg himself saw it and congratulated the designers. A film adaptation was also mentioned, but nothing came to fruition. The future creators of Oddworld also liked it, and two years later Abe was born, perhaps owing something to Heart of Darkness.

But the game was still far from complete, and it was back to the code mine for three years more years. The reason for this delay was that Amazing Studio had been much too ambitious in their conception of the game. They wanted it to feel and play like an animated film, they wanted the music to sound grand, the sound effects to be realistic, the voice actors to be perfect, the animations to be fluid and the gameplay to be as tight as possible. This made for an absolute gem of a game, but also for an incredibly drawn-out and difficult process which exhausted all of those participating. The soundtrack is particularly good, and is also the very first video game soundtrack specifically composed for and played by a symphonic orchestra (the Sinfonia of London). Unfortunately, it was technically beaten to the post by other games that managed to get released before Heart of Darkness.

The game was finally released in 1998 for Windows and PlayStation, a full six years after development had started (a Game Boy Advance port was announced and cancelled in 2001). The two versions are similar, apart from the PlayStation one lacking black borders on the side, thus stretching the image a bit, and also sporting many more colours than its Windows counterpart. After contacting Virgin Interactive and Sega, the French publisher Infogrames was finally chosen to distribute the game in France, and Interplay elsewhere around the world.

When Heart of Darkness was finally released, video game critics loved it for its beautiful in-game graphics and cutscenes, fluid gameplay and great atmosphere. But it was also taxed of being archaic, seeing how the PlayStation had championed 3D as the new norm of video gaming. Also, the fact that the PC version only had 256 colours VGA graphics, as opposed to the 16 million colors of the PlayStation version somewhat angered the computer crowd. Truth be told, even if the PS1 version does offer a bit more nuance in the colors, it is not a real handicap to the Windows version. The fact that the Windows port of Final Fantasy VII was released the same month may have also played a part in the game’s relative obscurity (that and the fact that video game testers were busy watching the football world cup at the time, which France won).

Sadly, and although it actually sold very well (around 1.5 million copies), the game’s long development cycle meant the bankruptcy of Amazing Studio. The experience left a sour taste in Chahi’s mouth. He realized that the industry was changing – the advent of 3D, the many small studios closing or merging into larger ones, bigger teams working on bigger projects. This, added to the exhaustion resulting from Heart of Darkness‘ development, prompted him to abandon this walk of life for some time, until the 2011 of From Dust. He then explored other passions of his, like painting, travelling, and photography, especially that of volcanoes. He later stated in an interview that he is fascinated by arid and inhospitable landscapes, like those to be found on the slopes of a volcano or in the lands of Another World and Heart of Darkness.

Links:

Éric Chahi Interview on chronicart.com (in French)

Éric Chahi Interview on grospixels.com (in French)