Pack-In Video was sort of like the Acclaim of Japanese publishers – much of their output was quick cash-ins outsourced to other developers, with results that were generally less than desirable. Hihou Densetsu: Chris no Bouken (“Secret Treasure Legend: The Adventure of Chris”) for the PC Engine CD is one of those titles, a painfully mediocre side-scroller with some anime cutscenes to take advantage of the technology. It was developed as one of the early titles by Arc Systems Works, who would later become internationally known for their Guilty Gear series of fighting games, but at the time mostly did outsourced development work for larger publishers.

Chris Steiner is a young woman, searching for her long-lost archaeologist father, who disappeared when investigating the Indio civilization in South America. Through the game’s eight levels, you fight against natives, monsters, and assorted spirits, until you end up awakening the spirits that lie deep underneath the surface, raising the long-forgotten city of Atlantis.

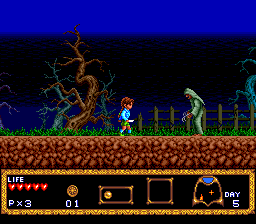

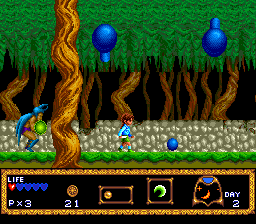

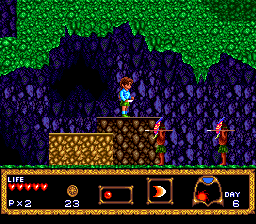

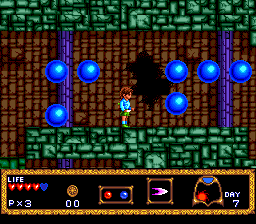

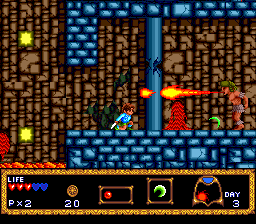

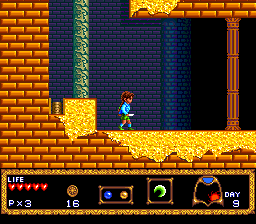

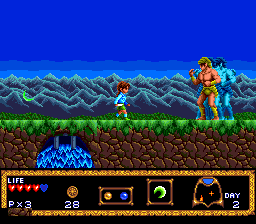

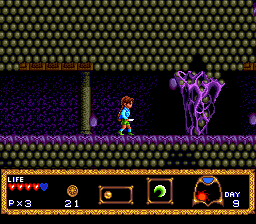

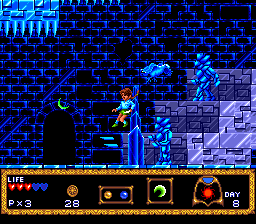

Chris’s default weapon is a dagger, which is pitifully useless. Thankfully, you can pick up and combine colored gems to create three different kind of projectile attacks – a standard shot, a “cutter” wave, and a boomerang. None of these are particularly thrilling, but they’re pretty much essential for dealing with almost any enemy. Rather oddly, the totems that drop power-up items tend to pop up behind you rather than being visible on the playing field, meaning you need to backtrack a few steps if you want to pick up anything.

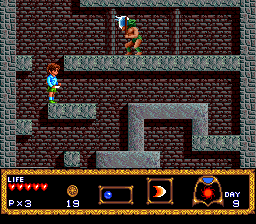

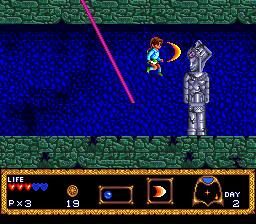

You can take five hits before dying, though since some enemies tend to leap out of nowhere, you either need to memorize their appearances or really take your time. The levels are broken up into halves, and while these areas aren’t long individually, you are sent to the beginning after dying. Strangely, one of the biggest foes in this game is the time limit, as you really need to keep up the pace to make it to the end. This proves to be the biggest issue when you need to scale areas full of disappearing/reappearing blocks a la Mega Man – technically you can miss a jump and fall to the ground without losing any health, but you have wasted precious seconds, which can spell the difference between success and failure.

The question is: why? Time limits were vestiges of the arcade era, and typically only made their way into console games as a way to provide scoring bonuses. Here, it seems like near the end of Chris no Bouken‘s development, someone played the game, realized it was kinda boring, and added the timer to add some tension, which is of course far easier than actually redesigning the game. The actual passage of time is also incredibly curious – at the beginning of each stage, you have a number of “days” to complete it, while day and night pass with a sun and moon in the status bar. It takes about 20 seconds to cycle a full day, so does that mean that you’re walking at the pace of two steps per hour, and you’re just watching and playing everything accelerated? Does the rotational orbit of the Earth work differently in this specific part of South America? It’s best not to think about it.

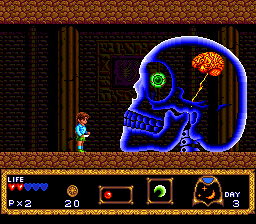

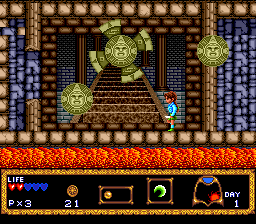

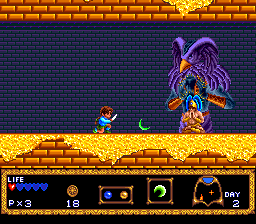

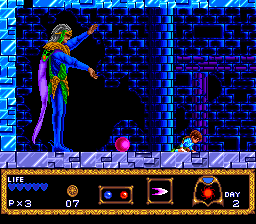

Outside of the many pop-up surprise enemies, the stages are pretty typical in design. A few of them have interesting gimmicks, some of which are obvious Indiana Jones references, like a section with a mine cart or an invisible bridge. One section has some kind of rival explorer who runs in and steals your power-ups, but the story doesn’t reference him so it’s unclear who it’s supposed to be. One area is a little more circuitous than others and requires solving extremely simple switch puzzles, which is nice just for variety’s sake. The first level boss – a giant transparent blue skull with a visible brain! – looks pretty darn cool, but most of the rest of the bosses are fairly boring. The final boss is just an evil guy approximately three times taller than Chris, and it looks more goofy than threatening.

The music is Katsuhiro Hayashi, a former composer for Sega who worked on games like Quartet, and also provided music for a couple of PC Engine games like Terraforming. Most of it is early 90s jazzy pop synth, typical of other CD games of the era – pleasant in its nostalgia, some of it good, some of it not. The exception is the seventh level tune, which uses pan flutes and an acoustic guitar as its primary instruments. It’s easily the best song of the soundtrack, though it can’t help but feel out of place, especially since it’s positioned so late in the game.

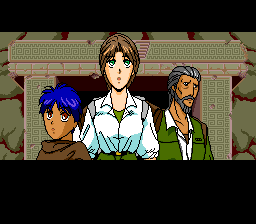

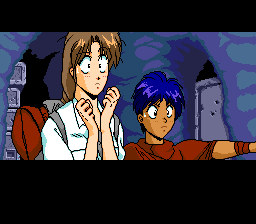

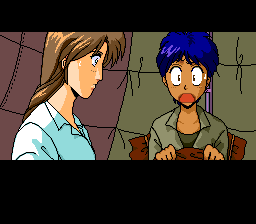

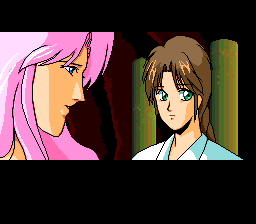

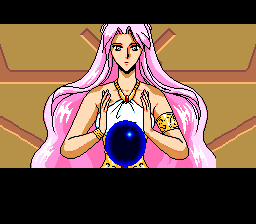

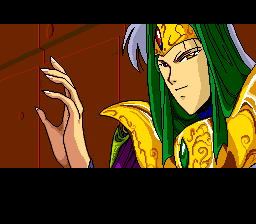

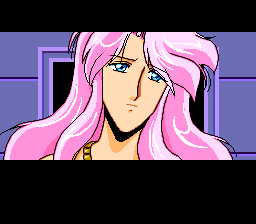

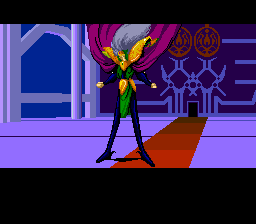

The character designs (or, at least, the cover illustration) sure look like they were provided Satoshi Urushihara, famous for his work on the Langrisser and Growlanser series. There’s no credit for it and it’s not just anywhere on his profiles, but if it’s not him, then it’s an incredible simile. In spite of the attractive designs, the artistry isn’t well reflected in the cutscenes, which are not only largely static but also inconsistent in quality.

The story itself is also not terribly good. At its release in 1991, it’s only two years removed from the NES Ninja Gaiden, itself a seminal point in video game storytelling. But the game worked so well because there was an underlying tension behind everything that not only provided purpose for each action but also context that weaved together the otherwise disparate levels. In Chris no Bouken, almost every level is just another deeper layer of the ruins, as Chris meets various characters, friend and foe. The first she keeps is a young Indio boy named Kachua who accompanies Chris on her journey. Next, she meets her father’s partner, Dr. Altmeier, who is, according to the manual, also a neo-Nazi. (Shockingly, he later makes a sinister betrayal and pays with his life.) Then you awaken the pink-haired woman Filia, who relates to you the story of Atlantis, before her evil brother Lagash awakens, who you then need to defeat. It’s all very whatever, though props to the production team for making a female Indiana Jones-type character and resisting the temptation to turn her into a sexpot.

Chris no Bouken isn’t unplayable, but it also stacks up poorly next to its peers. On the PC Engine CD front, there was Telenet and the Valis games, all of which were messy but at least somewhat fun. On the NES/Famicom, there were games like Vice: Project Doom and Totally Rad, again, not games that are all-time classics, but were reasonably well-put together. As such, it’s emblematic of the type of 16-bit CD game which attempted to use attractive art and voiced cutscenes to cover up a slapped together game.

Links:

http://www.chrismcovell.com/games_illustrated/arc-hihou_densetsu.html