The protagonist of Home is a nameless guy who wakes up in an unknown house with a wounded leg. Just in the next room lies the mutilated corpse of a man. Trying to find his way out of the property, he soon stumbles over details about the house and its inhabitants, but also more gruesome discoveries and unsettling connections to his own life.

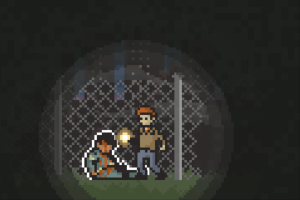

Home borrows many common horror tropes: The first person door animations are known from classic Resident Evil, and the whole world is covered in darkness, save for the dim light of a lamp, found all too conveniently just where the hero woke up. There are also some well-applied shock moments, like a cat that quickly jumps away as one walks toward it, but the most essential element of horror, a sense of immediate threat, is missing. It’s clear early on that there’s no actual danger lurking in the shadows.

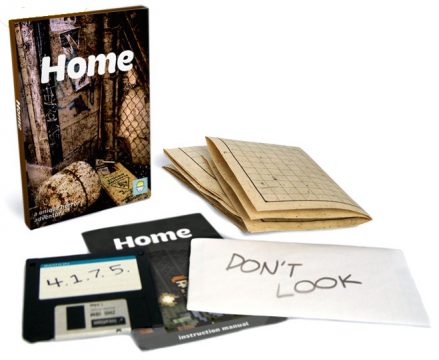

While Home can be completed within an hour, the game’s appeal is to do things differently upon replay and see what changes. Often that just means taking or leaving items, examining or missing clues. But some obstacles can also be passed in several ways. So in the beginning it’s possible to jump down a broken ladder at the cost of the hero’s hurt leg, while finding another means to descend saves him the pain.

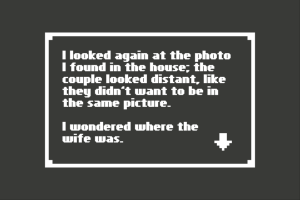

There are no “wrong” decisions, though. The changes are merely nuances in the narrative, and ultimately what the player learns about what happened. Piecing together the clues (aided by post-chapter summaries) is what Home is all about. The alternative narratives are cleverly crafted, but with neither failure nor success it becomes a matter of just limping through with whatever choices and then maybe get some other results by doing the opposite the next time. At the end awaits an optional twist that doesn’t really work out, as it renders earlier scenes meaningless.

It’s also questionable if the low-detail pixel graphics were the right choice for a horror game. The hero cannot but keep the same dopey look throughout the story, no matter what happens to him. Sure, it has been that way in countless great classics, but Home never gets all that disturbing due to the lack of visual nuances. The flashback-like narration in silent movie style cut-away text panels is neat, though.

Nonetheless Home is a fine exercise in interactive storytelling and other developers should look at it for inspiration. It is, however, not much of a game. Praised as “King’s Quest meets Heavy Rain,” all it got from the former are the blocky graphics. Puzzles never go beyond holding the lamp aloft to reveal items or pulling a lever more than once. Benjamin Rivers wants “evolution in the adventure genre,” to engage players on “that unique mental level.” Traditional adventure puzzles might not be the optimal way to tell an interactive story, but here there’s nothing “gamey” to replace them. Home‘s intriguing narrative is stunning, but offers no solution to the old problem of combining gameplay and story for the benefit of both.