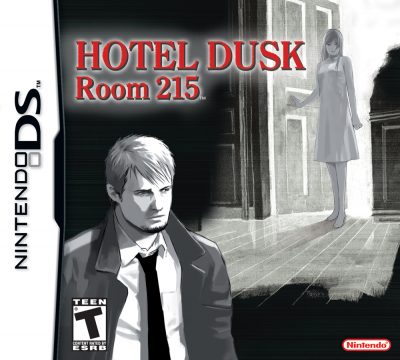

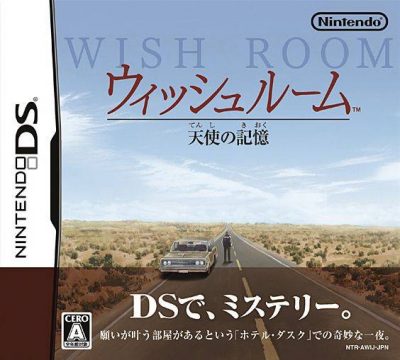

Relatively hard to find upon its initial release, Hotel Dusk: Room 215 was eventually re-released by Nintendo under their “Touch Generations” label, with a giant orange banner plastered on the cover unambiguously labeling it “A MYSTERY NOVEL”. It’s a fair enough description, and not only in the sense that it is one of the rare DS games played with the console held sideways, book-style. Hotel Dusk walks a very fine line between being an adventure game and being a straight-out read-through of a story. Fortunately, the story is sufficiently good, and so brilliantly presented, that it is hard to object to being led through it all by the nose.

There’s no denying that Hotel Dusk is a very, very linear game. The story takes place over the course of ten chapters, each occurring over either a one-hour or half-hour period on an evening in December 1979. As you might expect from similar games, such as the Laura Bow mysteries, Cruise for a Corpse, or The Last Express, the clock automatically advances after key events. However, there is almost always only one thing going on in the hotel at any given time: one place where anything is happening, and one place where you need to be. On the one hand, this structure allows for the construction of a tidy, straightforward narrative, with each chapter ending in a dramatic confrontation of one of the characters; on the other hand, the replay value is rather diminished, except for maybe exploring the various means of failing. (There is a “second quest” available if you start the game over after finishing it once, but the only changes are very, very minor and you have to get through most of the game before anything different happens. It was good of the developers to try, at least.)

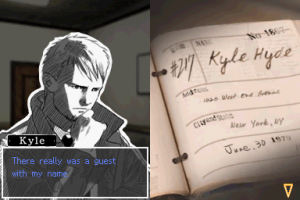

The story is concerned with one Kyle Hyde, a former officer of the NYPD who resigned following an incident which resulted in the shooting of his partner, Brian Bradley. As the story opens, Kyle is ostensibly employed as a traveling salesman, but all is not as it appears: Red Crown, the company he works for, also has a side business of discretely “finding things” for people. It is another such assignment that leads Kyle to Hotel Dusk in the Nevada desert – but naturally things don’t quite go as planned. In short order you are introduced to the hotel staff and Kyle’s fellow guests.

Characters

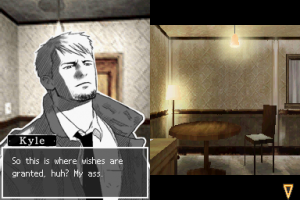

Kyle Hyde

Characters occasionally comment that Kyle’s brusque manner doesn’t seem to be particularly fitting for a salesman. Fortunately, some people also regard him as having the ineffable quality of a person to whom they can readily confess their various secrets.

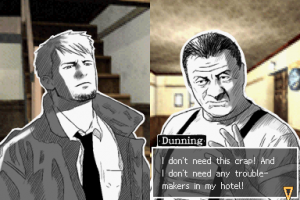

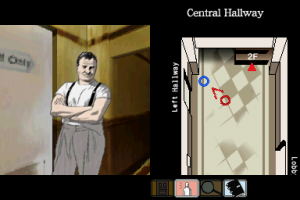

Dunning Smith

The owner of Hotel Dusk, and definitely not a people person. Dunning seems to be lurking around every corner just waiting to kick Kyle out, ending the game, as soon as you make the slightest wrong move. Is it just because he doesn’t like cops, or is there something more?

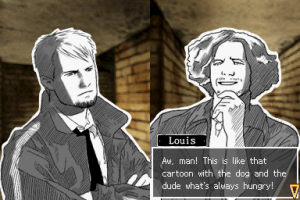

Louis DeNonno

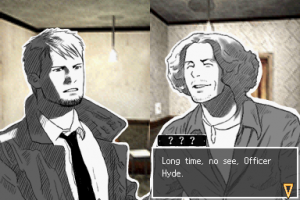

Surprise, surprise, there’s someone at the hotel who recognizes Kyle from his NYPD days. Louie is something of a slacker-hippie type who doesn’t work very hard at his various jobs at the hotel, but he’s ever-present and all too willing to help Kyle out over the course of his investigations.

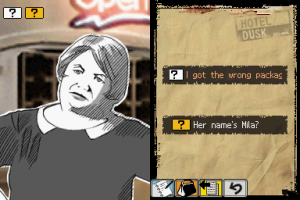

Rosa Fox

The hotel employee who seems to get the real work done, Rosa works as the cook and otherwise is busy keeping the hotel spotlessly clean when she’s not yelling at Louis. On more than one occasion, she dragoons Kyle into helping her out with various tasks.

Helen Parker

An old woman with an eyepatch, Helen checks in at the front desk just after Kyle arrives. She’s a little annoyed that Kyle is assigned Room 215, which, according to Dunning, has a reputation for granting the wishes of whoever stays there. It seems she’s after something.

Martin Summers

Martin is a novelist by trade and has a vocabulary that shows it. But why would a famous writer be at a hotel in the middle of nowhere?

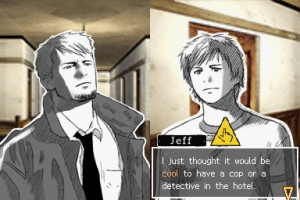

Jeff Angel

A rather obnoxious and rude young man, Angel succeeds in stirring up trouble for Kyle during the first half of the game, though he stays out of sight afterwards.

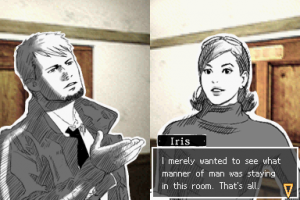

Iris

Yes, just Iris. Mysterious enough? A minor character, she doesn’t do much for most of the game except act very ticked-off about something. You find out what that is eventually.

Melissa Woodward

An innocent but somewhat cranky child, all Melissa really wants is to see her mom again.

Kevin Woodward

Melissa’s father. It may suffice to say that he is not out to win any parenting awards.

Mila

A real mystery, Kyle first spots Mila walking alone on the highway towards the hotel. Even more mysteriously, she doesn’t seem to be able to speak.

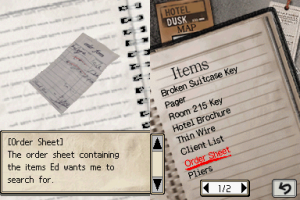

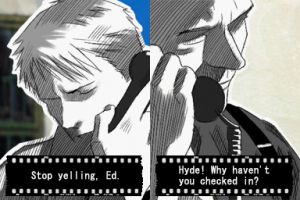

Ed Vincent

Kyle’s boss at Red Crown, still well-connected with the police, is just a phone call away to provide further information on what Kyle uncovers during his investigations.

Rachel

Ed’s secretary, with whom Kyle probably converses just about as much as he does with Ed. The game ever so subtly hints that she might have a thing for Kyle.

Brian Bradley

Absent but central to the plot, the discovery that Bradley was on the take during Kyle’s time at the NYPD continues to constantly haunt Kyle. Considering Kyle personally shot Bradley, it’s very odd indeed that Mila happens to be wearing a bracelet just like the one Bradley used to wear.

In sharp contrast to a lot of adventure games, Hotel Dusk is pretty serious. There’s hardly anything but dry humor to be found, and aside from some very, very brief references to the wish-granting properties of Room 215, everything is kept wholly realistic. Arguably the most contrived thing about the game is that there could be such a collection of characters assembling all at once, each with their own convenient little secret. That said, the game’s “T” rating from the ESRB almost seems a little harsh. Drugs are strictly limited to a relatively small amount of alcohol, at least in comparison to a lot of other mystery stories. Sex and romance, those other mainstays of detective fiction, are limited to the appearance of a “men’s magazine” that factors into the story just enough to suggest that there was some subplot tossed away during development. Aside from Bradley’s oft-mentioned untimely demise, death and murder are largely not even hinted at. A recurring element throughout the game is a crime syndicate known as Nile that seems to be entangled in some art thefts, and that’s about as bad as it gets. Look at it from the right angle, and you might see the game as a whole as a thematic morality tale about people with wishes of their own, and the lies they’re willing to tell and facades they’re willing to wear in order to get what they want.

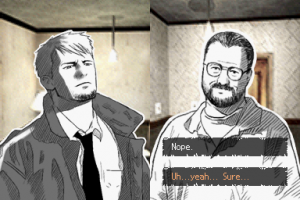

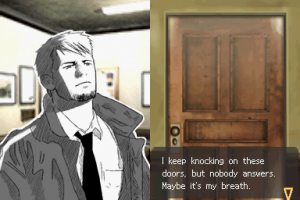

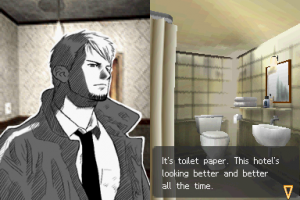

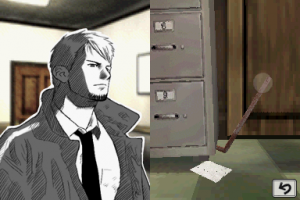

Probably the most striking feature of Hotel Dusk is its unique visual style. Readily compared to the music video for “Take On Me” by A-ha, each character appears only as a cut-out pencil sketch, with the sketches changing subtly from moment to moment. The characters consequently have a kind of lifelike quality that static portraits could never manage. While the portraits are all realistically done, there’s just enough detail left out that one’s imagination can readily fill in the details. Each character also has a considerable range of emotional responses – exhaustively animated through live-action rotoscoping – that they’ll go through over the course of a dialogue, and while some of them are obviously re-used, they remain remarkably expressive. (The one exception might be this weird kissy-face that Louie gets when he smiles, of which you see a good deal, considering how much you deal with Louie.) Combined with a top-notch script, in which each character speaks with his or her own distinctive mannerisms, it’s easy to get caught up in the story.

Further enhancing the presentation is a quality soundtrack worth raving about – an important attribute to have, as the game otherwise only has ambient sound effects. Generally consisting of smooth lounge-style jazz, it’s very fitting for the game’s noir mood and is perhaps only slightly marred by the synthesizer quality of the instruments. Particularly nifty is a track near the end of the game that seems to riff appropriately on Hotel California. There’s a jukebox in the game that will let you sample all the different tracks as they become available, though unfortunately it is only available during particular chapters.

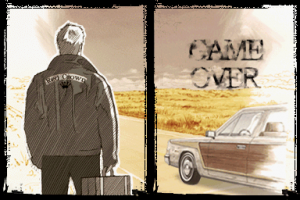

It is good that the music and character portraits work so well, as playing Hotel Dusk involves reading a tremendous amount of dialogue. A veneer of interactivity is spread over it to keep things engaging: you can typically ask questions of a character from a list in any order you choose, and occasionally, you’ll be given a choice of two dialogue options to choose from, or prompted with a flashing triangle indicating that someone can be pressed for more information. But most of the time, it’s all paper-thin: responses to questions are generally the same regardless of the order they’re asked in, choosing the wrong dialogue option will often just cause the dialogue to loop over so you can choose the right one, and even if you miss a flashing-triangle prompt, the question it would have brought up will just spontaneously occur to Kyle after the conversation is done. It’s possible to mess up the big end-of-chapter interrogations badly enough that Kyle gets discouraged and retires to his room (resulting in a Game Over), but you really have to go out of your way to make it happen. At least you have some incentive to pay attention, since at the very end of every chapter Kyle will pause to gather his thoughts, meaning there’s a multiple-choice mini-quiz about the events that transpired.

One of the game’s nods to non-linearity comes in the form of the hotel vending machine, which seems a bit poorly thought-out. There’s exactly one time period that you’re allowed to get the quarters you need in order to use the machine, which can dispense exactly four different food items, as well as a fifth item whose code has to be deciphered from clues scattered around the hotel. While none of them have any effect on the story, each guest reacts to each item differently – unfortunately, some will also take the item from you without warning and without any tangible benefit, which means you’re stuck re-loading if you want to hang on to the item to see if someone else has something to say about it. Again, it’s nice that the developers tried, but after doing so much to earn the player’s trust, these one-shots stand in sharp contrast.

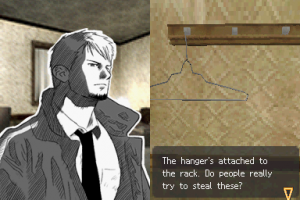

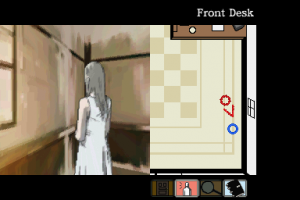

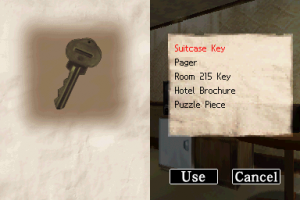

When you’re not chatting with someone, the main interface of the game features a simple 2D floor plan on the touch screen, and a first-person view on the other screen. Moving about often involves stopping to open doors, a feature that, like the controls, readily draws comparison to Resident Evil. The choice of textures in the first-person view sometimes seems a little weird, but given that the hotel is supposed to be somewhat dingy and run-down, it’s entirely forgivable. Approaching an area of interest causes a magnifying-glass icon to flash on the touch screen, which in turn allows the area to be more closely investigated in a zoomed-in perspective that can be rotated with a one-dimensional slider. This being the DS, every object is rendered in relatively simplistic low-poly models that stand out neatly from the background, though some objects provide a digitized photo if you examine them further.

What this all boils down to is a very reasonable alternative to the obnoxious pixel-hunts from the 2D adventure games of yore: you have to do just enough hunting around to present a little bit of a challenge. The game could probably function just as well if you just jumped from location to location via a menu, as in the Phoenix Wright games, but being able to wander around freely does wonders for immersion, even if it’s largely unnecessary. It’s also worth pointing out how remarkably detailed everything is. For example: as you might expect, every room in the hotel has a bathroom, and every bathroom pretty much has the same fixtures, and yet each time you examine a different stack of towels or gleaming toilet, you’ll actually get a unique description from Kyle. Someone actually came up with around a dozen different ways to comment on a roll of toilet paper!

Puzzles are also neatly streamlined. Kyle occasionally remarks that he should write something down in his notebook (which is your cue to do so), but most of the time anything you should have written down just comes up again naturally. Abilities such as hiding objects in Kyle’s suitcase are neatly but discretely spelled out, and the game does a very careful job of making sure you never have unnecessary items on hand. A good example comes early on in the game, when you have to pick a lock. Another game might let you hold on to your improvised lockpick for the rest of the game, and let you futilely struggle with every locked door in the hotel, but once Kyle is done with it, he just decides to put it away, and that’s the end of it. You’ll also never have to combine two items in your inventory directly, saving you from trying to use everything on everything else: at most, you’ll be able to use an item on some object in the room, and then use another item on the same object. Typically, such a use will bring up a simple little touchscreen minigame: unfolding a paperclip, shaking a box, and so on, all neatly enhanced with realistic sound effects. Once again in stark contrast to many other adventure games, pretty much every such minigame would function perfectly well in real life. Often criticized is a twenty-piece jigsaw picture puzzle belonging to Melissa that you’ll have to deal with two or three times, but given that it’s only twenty pieces, it is hardly worth getting worked up about. Puzzles really only start to unravel a bit towards the end of the game, but even then you don’t have to deal with anything like the bizarre mechanical contraptions of, say, Syberia or Sanitarium.

Despite the game’s earnest efforts to keep you anchored firmly to the rails, the ease with which you can bring the wrath of Dunning down on Kyle’s head is almost reminiscent of Sierra at its worst. Ask the wrong question, or get caught with the wrong item at the wrong time, and he’ll kick Kyle right out. Nonetheless, on those rare occasions when it isn’t perfectly clear what you shouldn’t have done, you’re never left wondering exactly what happened, and the game is generous about letting you continue from where you messed up. There’s a bonus scene at the end of the game if you stick to reloading saved games rather than letting the game give you a do-over.

Getting kicked out is still slightly preferable to getting completely lost, of course. Fortunately, the hotel slowly opens up as the game progresses, and even once everything is unlocked it’s still a relatively small place. You can usually figure out where you’re supposed to be at any given time, especially if you pay attention. The only particularly unforgivable puzzle comes relatively early on, when you’re supposed to knock on a character’s door. Inexplicably, the dialogue will only proceed properly if Kyle is carrying certain items, and they’re items that would have gotten Kyle booted if they were in the inventory moments earlier.

Hotel Dusk: Room 215 is unquestionably a solid piece of work, with the kind of finely-polished script that makes it hard to tell it was ever a Japanese game to begin with. The developers even included extensive support for left-handed controls and even the DS Rumble Pak, of all things. In the end, your enjoyment of the game comes down to how willing you are to sit back and enjoy the unique presentation of the tale of Kyle Hyde’s investigation. If you’re looking for a game in which you’re going to have to think even a little about your choices and their implications, you’d best look elsewhere.