It doesn’t get much discussion nowadays, but gaming as a whole has a lot to thank Konami’s Maze of Galious for. As one of the highlights of the MSX library, Maze of Galious offered an expansive, mystery-laden world to explore, full of enough danger to scare away all but the most intrepid of adventurers. It’s a challenging, obtuse game, but it rewarded players who persevered and it also helped codify the then-nascent “Metroidvania” genre. Not only did it influence notable games from major developers, such as Konami’s own Castlevania II, it also inspired several indie developers to make games in a similar vein, including the likes of La-Mulana and UnEpic.

Released in 2011 by Eiji Hashimoto (aka “Buster”, the same name as his debut 1995 Sharp X68000 title), a longtime Japanese indie developer, Hydra Castle Labyrinth (or Meikyuujou Hydra in Japanese) is another game inspired by Konami’s perplexing adventure that’s worthy of recognition despite its absence from modern storefronts. The game gained attention when Let’s Player Deceased Crab did videos on it, inspiring Reddit user Gary the Krampus to translate the game into English. Hydra Castle Labyrinth is unremarkable by today’s standards on a surface level – a Metroidvania with retro graphics and ideas similar to classic 8-bit video games like Castlevania and The Legend of Zelda? Sounds like something you can find by the truckload on Steam! Look past that, though, and you’ll find a game that accomplishes a specific mission with aplomb: taking the smart game design and exploratory thrills of Maze of Galious and making it all palpable to modern audiences through quality of life tweaks and fewer mechanics to disrupt the pacing.

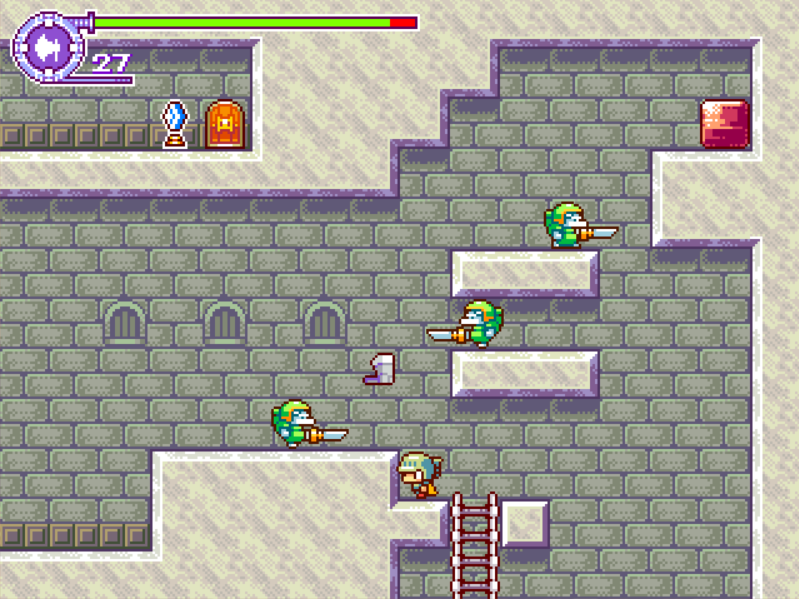

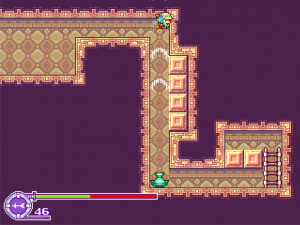

In Hydra Castle Labyrinth, the only story to be found is in the readme file included with the download; there’s zero exposition in the game whatsoever! Your goal can also be (mostly) extrapolated from the game’s title: navigate the Hydra’s labyrinthine castle, find the eight dungeons, and defeat their bosses to reclaim the crown. You’re dropped into the labyrinth without a map or any guidance on where to go, leaving only your tiny sword to protect you. All of this likely sounds eerily familiar to those who have played Maze of Galious, but as you get acquainted with the flow of the game, you’ll find that a lot of the rougher edges and eccentricities have been dialed back or removed entirely. You only have a single playable character, save points are placed in front of every dungeon, and you won’t have to type anything out or solve complicated puzzles to make progress. The Hydra’s castle is smaller than Konami’s beloved maze and dungeon keys after the first are doled out in linear fashion as you defeat each boss, meaning that players will never end up in over their heads. Serving as a smart example of guidance through environmental design, the castle is also structured in such a way that the early dungeons are located near the top of the castle, the later ones are located towards the bottom of the castle, and the Hydra’s lair appears right in the middle.

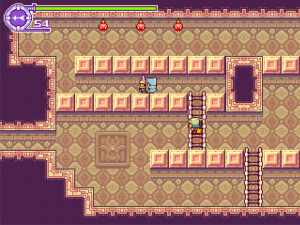

While the knight you control doesn’t start out with much, a bit of exploring will quickly inundate you with useful items. The first item most players will find is the pickaxe, which allows players to break blocks, leading the way to the first dungeon key and a whole lot of other secrets. Finding the shield lets the player block projectiles by standing still or by holding the shield upwards, something that’ll be immediately useful in dungeons two and three. From there, many of the game’s items are entirely optional, though some dungeons, namely the fifth and sixth ones, will be miserable without protection against the status effects found within them. Missing out on things like the double jump or the ability to charge your sword strikes would be painfully likely if not for the inclusion of a bell item, which rings whenever a hidden item is nearby. This item averts one of Maze of Galious’s most intimidating design choices by preventing players from getting stuck due to being unable to find an item that was hidden in the most sadistic way possible. Much like sequence breaks in Metroid games, savvy players can use knowledge acquired from previous runs to get the double jump earlier than expected, allowing them to trivialize all of the game’s platforming challenges and empower them in that special way only Metroidvanias can.

There are five subweapons to be found as well, which grant you additional attacks at the cost of ammunition, just like in Castlevania. Arrows can be shot in a straight line, axes are thrown upward on an arc (sound familiar?), boomerangs are self-explanatory but no less effective for it, fireballs roll along the ground and hit multiple times, and bombs deal big damage at the cost of being able to hurt the knight. Each subweapon is enormously helpful and complements the middling range of your sword in various ways, allowing you to attack from every angle you could want. Stocking up on ammunition is best done by slaying foes, providing incentive to fight what you encounter without having to force in a basic RPG-style experience system.

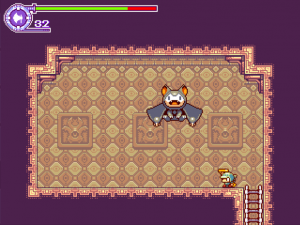

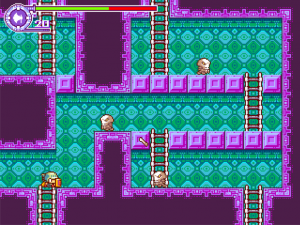

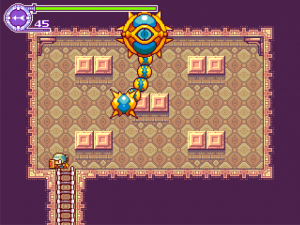

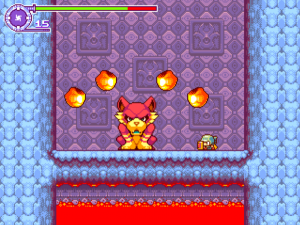

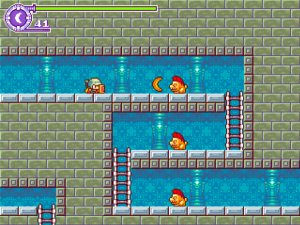

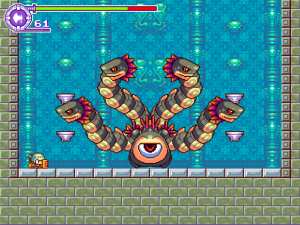

Dungeons are the meat of the game, containing sequences of connected rooms full of nasty foes and environmental hazards. Like Zelda, dungeons contain an item that’ll be useful for clearing the very place that hides it. The first few dungeons are brief and basic, but the ideas quickly ramp up from there, testing the player in different ways. The fourth dungeon is water-themed and the protagonist can’t breathe underwater by default, requiring the player to stay on the dungeon’s upper platforms to avoid falling into the deadly brink. To make things even more vexing, it’s the only case in the game where a required item is hidden outside of the dungeon! Dungeon five forces the player to wade through the darkness before they can find a candle to illuminate their path and dungeon six brings in the infamous disappearing blocks from Mega Man to give the platforming a bit of proper challenge. Bosses are simplistic, only having a few attacks at most, but said attacks are dangerous enough to wipe you out quickly while you learn their patterns. In contrast to the breeziness of the rest of the game, bosses are excessive battles of attrition, requiring what feels like dozens upon dozens of hits before they finally go down.

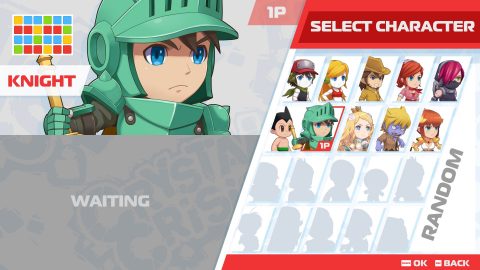

Hydra Castle Labyrinth is impressively lean; there are no NPCs, no instances of dialogue, no RPG mechanics, no instances of inventory management (item effects are always active), and healing can only be done at save points and via occasional drops. This leanness does come at a cost, however – Maze of Galious’ idiosyncrasies are part of what gives it a special kind of texture, a distinct sense of memorability through friction, and Hydra Castle Labyrinth is breezy enough that it can be finished in two or three hours, which may leave diehard fans of its inspiration seeking something more capable of leaving a lasting impression. In the context of Hashimoto’s portfolio, this game is among his biggest and most ambitious, eclipsing the scope of his works that came before it while also playing to his strengths of understanding what made the classics great and knowing how to present their ideas to an entirely different generation of gamers. Hydra Castle Labyrinth hasn’t received a follow-up despite being Hashimoto’s most widely recognized game, but the knight lives on through Nicalis’ 2019 puzzler Crystal Crisis where he’s a playable character with his own theme written by Hashimoto and Yann Van der Cruyssen.

In 2017, publisher Nicalis tweeted out an image teasing some of their upcoming Nintendo Switch ports, including a partially cut-off icon for Hydra Castle Labyrinth. Curiously, that particular Switch port never came to be, though a GBATemp user by the name of Rinnegatamante would go on to create a homebrew Switch port a year later. Other homebrew ports were created for Linux, Dreamcast, PSP, Vita, 3DS, and Wii. All versions have the same content, but each version includes additional options, such as the ability to enable an in-game timer and a fullscreen option for the PSP and Vita. The 3DS version goes even further and uses the bottom screen to display your inventory alongside 3D support that works rather well. The Wii version provides a 240p mode for use with CRTs and allows for multiple controller options. Considering that the PC version can be surprisingly taxing on a computer’s CPU usage (leading to frequent stuttering), the console ports come recommended for those who can get them up and running.

Links

- https://nintendoeverything.com/nicalis-also-seems-to-be-planning-hydra-castle-labyrinth-for-switch/ – Article regarding the Nicalis-published Switch version that never came to be

- http://hp.vector.co.jp/authors/VA025956/ – E. Hashimoto/Buster’s website

- http://www10.plala.or.jp/bb/zac/index_e.html – Debugger/Tester ZAC’s website

- http://www5c.biglobe.ne.jp/~mataz/index.htm – Composer “MATAJUUROU”’s website

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AYJnuets5t8 – The Knight’s theme in Crystal Crisis

- https://www.romhacking.net/translations/1700/ – Link to the translation patch

- https://www.reddit.com/r/IndieGaming/comments/hlwfc/i_wrote_an_english_translation_patch_for_hydra/ – Reddit thread where the translation patch was originally released