To what extent is the term “surreal” applied to video games? Not often. Which is odd, because in a medium that allows you to take screwing with your audience to another level, you’d think more would take advantage of it. Somewhere in their interactivity is potential to reach the oft-debated status of “art” they’re capable of being. That isn’t to say some haven’t tried, but they’re mostly swept under the rug as amusing oddities (LSD Dream Emulator) or go unrecognized entirely (Bad Day on the Midway, Chu-Teng). Hylics is a step forward in this sense, but mostly for being just another cautionary tale.

It’s impossible to talk about Hylics without immediately addressing its visuals. On their basis alone the game can well be assumed as some kind of premiere subverter, a definitive example given when one proclaims “yes, games areart!”. It’s hard not to be amazed – they’re gorgeous, with a psychedelic style that ranges from rotoscope, to claymation, to digital, all of which blend together seamlessly to make something utterly unique to Hylics and Hylics only.

They’re all the lush brainchild of Mason Lindroth, somewhat of a new age Yves Tanguy or Max Ernst, taking the absurdity of today’s world and churning it into a squishy, fever-dreamed fantasy. The malleable characters and environments within are no far cry from his other work and Hylics can be viewed as the ultimate culmination or portfolio of what he has produced thus far. His previous efforts have been some small game jam titles, all sharing a similar trademark surreal spectacle that’s shocking on first viewing; no other games have looked like this.

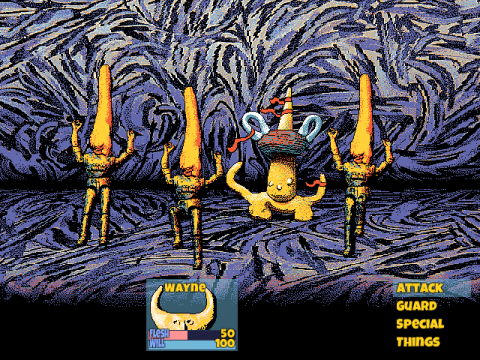

But admittedly aside from being a sheer visual opus there isn’t much else going on in Hylics. The “plot” is fabulously simple: your name is Wayne, you are a crescent-moon man thing and you live in a strange clay-like world where strange, but rather uninteresting things happen. After an introductory cutscene you begin the game in your home, where you have a cat, a bathtub, and a curiously intractable tele-set. That’s about the extent of the story, and though the game tries to sprinkle in some nonsensical bits and pieces of narrative through its course, it’s never nearly enough of a foundation to stand on its own.

The issue, of course, is not that the story is simple but that it lacks one entirely. There’s no attempt to make any kind of narrative, even an absurd or incoherent one. Each time there appears to be an overarching plot it turns out to be a banal red-herring, including a so-called tyrannical king and a caped man who sets off “acts”, both of which do exist, but exist only.

In these sections and throughout the rest of the game strange, pseudo-poetic verses are often spoken, and carry no meaning. They’re most comparable to the work of a stripped-down and incredibly juvenile E.E. Cummings, though in this case it doesn’t just appear to be random gibberish, it is. NPCs populate this world and exist, too, and don’t serve any other purpose. Many speak in the same bizarre word salad nonsense, but others talk entirely casually, normally, like people would. When not mildly amusing, it mostly just takes you out of the experience because the two extremes end up totally clashing.

The atmosphere emanates a pervasive yet modest laziness. Advertised as “a recreational game with light JRPG elements”, Hylics is just that. During the span of your playthrough, you recruit several party members who tag along in fairly standard yet engaging combat. The protagonists (especially Wayne) have an aesthetically compelling design but are memorable only for their design alone. Personalities are absent: if every line of dialogue they spoke was taken and presented at-random, there’d be no way to tell them apart. This is why there’s plentiful fanart of them, and virtually no other fan media for Hylics.

The battles you partake in with them are surprisingly balanced, hitting a nice groove – being rather challenging without being ridiculously difficult. They’re fun and varied, as are the enemies and attacks you perform. It’s nothing special, nothing more or less than traditional RPG-Maker Earthbound-esque bouts. But as more and more pile up, they quickly become repetitive. Exploration isn’t very enjoyable either, as you end up backtracking constantly to get all the content out of the game. To aid this, dying/losing is used as a mechanic of sorts, serving as a lite quick-travel feature, but it still takes a good amount of time to get from one place to another.

The adventure starts to feel rather tacked-on. It’s as if everything but the visuals were a contrived mechanism or tool that existed just because for it to be a “game”, they needed to. As far as unforeseen and unusual events, everything that happens is incredibly predictable from a standard RPG game-perspective. The game is much too-quick to let up on its oddity, and stops delivering almost immediately on everything but its visuals. The intrigue of the world, characters, and story all fade away when you realize there really is none. You fight, you explore, and eventually, you beat the game. Nowhere are the conventions of the game tested. And while it doesn’t necessarily need to, Hylics’ ever-present potential begs for it.

Wasted potential becomes tangibly part of Hylics, and is as much a component of the game as the rest of it is. Take, for example, the fade to black before a fight with a particularly grotesque enemy (of which the game has many). A hundred things can happen – another room, a strange and inexplicable landscape, genuine intrigue of some kind. The game doesn’t even consider the possibility. But hey, at least you can use a frozen burrito as a projectile, or microwave and eat it to revive yourself.

Without a world to get lost in, or characters to care about or be invested in, your motivation for playing becomes the art. The issue, however, is that they steadily begin to wear off on the player. The first twenty to thirty minutes are awe-inspiring, but the effect is short-lived because the game fails to deliver on its other aspects. Even the music, which at first is curiously quirky, becomes grating at a certain point. Everything sours at once. The world becomes no longer weird and instead contrived and boring and normal. And it almost feels wrong that a game so strange can turn out to be extremely standard. The very, very worst thing a weird game can be is normal.

Like Hylics’ JRPG predecessors (OFF, Space Funeral, Earthbound), it contains just as much of the absurdity and oddities, but it struggles to retain the cleverness, or lasting impact. The surreal world found within is abound with a limitless imagination, the notion that anything of the absurd can happen. The problem, of course, is that it doesn’t. While the unorthodox creative visuals undergo constant unbelievable mutation, the substance never has a chance to form. Much of the text in the game is randomly generated, which ironically becomes a metaphor for Mason Lindroth’s work – chaos without purpose. There is no method to its madness. But the art is so regardlessly fantastic, it can’t help but instill profound inspiration. The medium of the video game is used to induce a greater layer of interactivity, but it ends up backfiring, as player interaction only further exposes the lack of any real material underneath.

Below a brilliant surreal exterior, Hylics is really just a generic RPGMaker game with nothing else special to it. Yet it remains so unassumingly odd in a sea of stale and tame video games that it’s somewhat able to pull together on its ridiculous and highly original vision alone. The art does shine through in the end, and makes the three-dollar admission price worthwhile. It lacks the material and spirit to be anything more but never gives off the impression that it aspires to be anything more. Hylics is not art, but its art is still a beautifully interesting diversion. Through the clutter occasionally true bits of fervor will rear their head. Potential is ever-present, and even when it’s not realized, Mason Lindroth still manages to capture the vivid beauty of pulp. It’s just frustrating that even when Hylics valiantly fails, it feels like a success.

Links:

Mason Lindroth’s Games

Mason Lindroth’s Art