As one of the oldest companies in virtual entertainment, Atari has been through all sorts of phases and changes in its tenure. From their humble beginnings in adapting Spacewar! to cabinet form as Computer Space and remodeling the Magnavox Odyssey’s Tennis into Pong, they would branch out into the home console market with the Atari 2600 while continuing to make arcade titles. They hit hard times in 1983 (which continued into 1984) when their quality control failed to detect a glut of poor 2600 titles and effectively incurred a crash that let Nintendo pick up the ball they dropped and promote the NES in America. Atari’s finances never quite recovered from this blow and they had to sell the rights of their console division to Jack Tramiel (formerly of Commodore) in order to stay afloat, but their arcade division remained as Atari Games. Just before this transitional period came a bizarre and relatively unknown Atari title that attempted to revolutionize the way games looked, but it never achieved adequate notice. Deriving its name from Isaac Asimov’s short story anthology on artificial intelligence, it was labeled I, Robot. While it looked amazing for an early eighties release, it just may have been the wrong game at the wrong time.

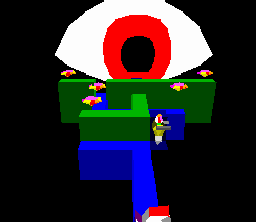

I, Robot is a milestone in video game history, as it was the first commercial video game to feature graphics made entirely out shaded 3D polygons. Instead of other 3D games which used vector graphics at the time (such as Tempest and Star Wars), I, Robot’s terrain and characters were all filled in with full color. To think that, before Star Fox used the Super FX chip and Quake popularized 3D models for first-person games, Atari beat them all to the punch a decade earlier. The game’s sound wasn’t any more advanced and is relatively sparse alongside the sound effects, but the graphics were marvelous for 1983. Its design is actually complimented by a small bit of story in which you essay the role of “Unhappy Interface Robot #1984,” a work droid in a futuristic regime watched by a giant floating blue head called “Big Brother.” As if Asimov’s influence wasn’t apparent, now we have a huge dose of Orwell in the mix! Whatever the case, UIR-1984 rebels against BB by… converting blue squares into red and destroying a giant floating eyeball that represents the evil overlord. It doesn’t make a lot of sense, but it doesn’t have to when it has those graphics.

Enough of how it looks; how it plays is relatively simple but can be a bit baffling at first. There are two distinct phases in each level: The platforming phase and the flying phase. The platforming levels involve you guiding the rebellious service droid over all of the blue terrain which becomes red as you move him over it. You must convert every blue square to red in order to get rid of the shield guarding Big Brother’s Eye. If you move off of the edge of a platform, you will automatically jump to the closest platform and instantly build a bridge between the two points. However, if the eye is open in the background while you are jumping, it instantaneously vaporizes you due to jumping being illegal and the punishment hence being death. You also have to deal with all sorts of obstacles, some of which can be destroyed (birds) and others which cannot (boulders). The vulnerable targets can be hit with your bullets, but they only fire north.

Get past all of the obstacles and hit the last red square to zap the eyeball, which prompts your transition into the flying phase. You simply have to dodge all of the space debris and land on the platform for the next level, but shooting rocks and tetrads out of your way helps clear the path and earn you points. You can even bag one of the seven characters from the game’s title (including the comma!) and grabbing all seven nets you a bonus life. The game carries on like this for twenty-six levels (an impressive quantity of variety for the time) with increasingly difficult hazards until you get far enough to loop the stages over, where the color palette changes and repeats the maps anew. Sometimes, the ends of platform levels will throw you into a bizarre maze where you collect jewels and vaporize the eye before a buzzsaw shreds the maze apart. Some shooter levels also involve you taking on Big Brother itself, which spits spikes that you absolutely cannot avoid and must destroy before they loop behind you. These sort of “boss” levels tend to be the most aggravating stages in what’s already quite a tough game, but if you run out of lives, you can enter a teleporter to warp you ahead to the last stage you were at as a sort of continue feature, although you can only use it so many times before it disappears and you have to start fresh.

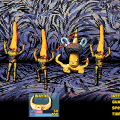

Despite the game’s overall psychedelic techno design, it features something even wackier than the main game. On the menu, you get the option to pick either the actual game or “Doodle City: The Ungame.” This little slice of Dadaist programming is essentially a very prototypical version of Kid Pix, Mario Paint, or whatever computer art application you favor. It enables you to cycle through all of the game’s character models and draw patterns with them, not unlike the Stamp feature from Mario Paint. You can spin the models and clear the board at will, and you even get an options menu that, among other things, allows you to return to the main game of I, Robot, although each minute you take in Doodle City consumes one life of the main game. It’s a strange yet fun distraction that’s amusing to play if the main game gets too frustrating.

I, Robot was certainly a game far ahead of its time, perhaps a bit too far for its own good. It was a critical and financial failure, perhaps due to its esoteric design and unorthodox gameplay, not to mention the high production costs of its special hardware of the time. Considering Atari’s aforementioned financial problems around its time of release, their bleeding funds and general disinterest in I, Robot only caused approximately 1,500 overall machines to have ever been made. If not the best game Atari ever made, it does stand out as one of their strangest and most unique releases which has achieved more notability in retrospect than it did back when it was new.

There were apparently plans to bring the game to the 2600 at the time, making it play akin to the arcade but with a more straightforward overhead 2D perspective. This idea was junked, likely due to the low popularity of the arcade parent. Atari Age actually featured a “ROM” of a long-lost beta for the 2600 version, only to have the ROM in question read a colorful graphic of “APRIL FOOLS” when booted.