You might think that the best time to examine a trendsetting video game would be at the height of its relevance and popularity, but sometimes it’s just as interesting to look at works whose moment has, for the most part, passed. I Wanna Be the Guy may be known today mainly for the legions of fangames – of wildly varying quality – that it spawned, the Retsupurae memes regarding how clichéd it became as a subject of Let’s Plays, and for potentially popularizing the kind of trial-and-error – or more accurately, trial-and-death – gameplay that has impressed and infuriated players in equal measure (well, possibly just a tad more infuriated) for the last few decades. But behind all of the jokes, the rage-filled videos of people falling for the game’s traps, and its memetic status as the intentionally unfairly difficult video game, it could be argued that I Wanna Be the Guy is legitimately one of the most influential games of the 21st Century.

For freeware games, it brought attention and legitimacy to an entire subset of work that had previously been written off as unprofessional, or not worth the same level of recognition as ‘official’ games. For mainstream games, it was a sadistic love letter to older consoles and franchises that a generation of programmers had been brought up on. And for indie games, I Wanna Be the Guy was one of the first titles to implement a challenge that was based not on conventional difficulty, but by predicting which paths a player would take, which patterns they would recognize, and how they would react to spur-of-the-moment threats, all so that they could be manipulated into losing in the most unexpectedly comedic fashion again, and again, and again.

Released for free in October 2007 by Michael “Kayin” O’Reilly, the hardest part of describing I Wanna Be the Guy– or to say its name in full, I Wanna Be the Guy: The Movie: The Game – is not just cribbing entirely from Kayin’s own webpage, which accurately describes it as “a sardonic loveletter to the halcyon days of early American videogaming, packaged as a nail-rippingly difficult platform adventure”. While the game has many recognizable influences from the most notoriously-hard old-school titles of the time, the one particular game that inspired Kayin the most was a Japanese Flash game titled “Jinsei Owata no Daibouken”, which translates to English as “The Big Adventure of Owata’s Life”. Much like I Wanna Be the Guy, this game was a combination of overtly difficult platforming and unexpected traps that would be impossible to dodge without prior knowledge, but Kayin believed that this concept could be improved upon. Ironically, Jinsei Owata no Daibouken was unfinished when Kayin had first played it, and it wouldn’t be finished until I Wanna Be the Guy was already released, and as such, the final area of the Flash game that had motivated Kayin to create I Wanna Be the Guy ended up being a parody of I Wanna Be the Guy itself, the very game it had inspired.

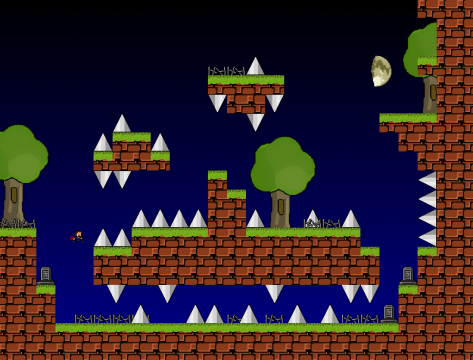

A good way to outline the kind of challenge you will be facing in I Wanna Be the Guy is to simply describe the first trap you are likely to encounter. When taking the upper path, The Kid walks under some trees bearing delicious fruit, and when you step underneath a fruit, it plummets down at faster speeds that you can probably react to and kills you in one hit. Having learned your lesson, you reload your save and try again, this time making your way carefully through the deluge of falling fruit by tentatively getting close enough to trigger them to fall and then safely retreating. Not all of the apples fall, which makes it harder to judge when you need to move, but it’s not the most challenging task in the world. Satisfied to have beaten the first obstacle in your path, you double-jump up to the higher platform that is clearly the way forwards. The apple beneath the platform falls up and kills you.

… The apple falls up, and kills you. Well, they’re more like giant cherries.

This is frustrating, unfair, a little bit funny, and genuinely excellent game design. I Wanna Be the Guy takes advantage of common video game tropes, or any patterns you might pick up from recurring traps, and then subverts them in order to kill you again. To some, this understandably feels like trolling, but it can also feel like a joke that the creator is sharing with you; taking famous, established concepts from familiar video game series, such as not being able to die in a cutscene before a boss fight, not placing an initially unavoidable trap at the end of a particularly challenging section, or not being hurt by items that are clearly part of the background, and turning all of these ideas on their head to highlight how comically unfair it would be if these rules no longer applied.

Not every trap you encounter will be this manipulative or intelligent, but behind every single one of them was the accurate prediction that you would likely be caught off-guard, and more often than not, Kayin was correct. It would certainly be a stretch to say for sure that this kind of predictive design was unique to the game, or that it was the sole inspiration for other indie games that put similar tricks to good use, but this also isn’t that far away from the fourth wall breaking tricks seen in Pony Island or Undertale, or introducing you to a trap by first having it kill you, as seen many times in the Dark Souls series.

What helps I Wanna Be the Guy to remain playable in defiance of this mockingly unfair difficulty, is the frequency of save points. The game has four difficulty settings; Hard, the default which provides save points roughly every two rooms, Very Hard, which reduces them considerably, Medium, which provides several more but labels them ‘WUSS’ and adds a pretty pink bow to The Kid’s sprites (Kayin has stated that while there was no ill intent, they regret the implications of this decision), and Impossible, which removes every single save point in the game. Kayin’s initial reaction to someone beating the game on Impossible difficulty – that is, a completely deathless run through the entire game – was understandably “holy crap your [sic] not serious are you”.

The inclusion of save points and the omission of any kind of lives system are why I Wanna Be the Guy remains so fun to play. Compared to many of the games it parodies – Castlevania,Mega Man,Ghosts ‘n Goblins – I Wanna Be the Guy is undeniably much easier and more forgiving than the titles it pays homage to. Once you’ve learned where all of the traps are – presumably by falling for them – then the timing and reflexes required to survive are no more difficult than the majority of other games. The most difficult parts of the game by far are the sections where traps take a back seat to more traditionally challenging platforming gameplay, which Kayin also excelled at designing.

Once you’ve gotten past the difficulty, Kayin’s creativity truly begins to shine.The game plays like a tribute borne out of sincere appreciation and nostalgia for the NES/SNES era of video games, and while the majority of the gameplay is fairly standard platforming with a double-jump, there are standout moments in the game where you’re traversing through the first screen of The Legend of Zelda, using Link as a platform while trying not to get stabbed by him, hopping into the Vic Viper from Gradius for a brief unexpected shoot ‘em-up section, or my personal favourite, falling into a game of Tetris and having to survive amongst the falling blocks whilst making your way to the top quickly enough to escape before you run out of time, and are promptly crushed by a giant Dr. Mario pill. It’s brilliant.

The creativity continues into the boss fights, featuring encounters with Mother Brain from Metroid, a kaiju-sized Mike Tyson from Punch-Out, and Dracula as he appeared in Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, complete with the opening speech redubbed in the Kid’s squeaky high-pitched voice, and the wine glass that Dracula contemptuously tosses aside actually killing you unless you move out of the way.It’s clear that Kayin has a lot of love for retro video games, and it shows. Despite the bosses, enemies and source material frequently being made the subject of mockery – upon defeat, Dracula screams “Behold my true form, and despair!” and anti-climactically turns into a Waddle Doo from Kirby, which is killed in one hit – it’s never as crude as you might expect from a mid-2000s freeware game.

The soundtrack for the game mainly consists of recognizable tunes from Mega Man, Metroid, Mario, Castlevania, Zelda and the like, but Kayin also threw in a few curveballs. The boss fight against a giant robotic Birdo from Super Mario Bros 2 is backed by one of the boss themes from Ikaruga of all places, the Castle of the Guy uses the work of legendary composer Rob Hubbard, in particular the theme to the Commodore 64 game Monty on the Run, and if you look up the soundtrack to Guilty Gear Isuka, most of the comments will be about I Wanna Be the Guy, as it’s where the game’s menu theme and the background music of the first area come from, as well as the memorable eight-second guitar riff that plays every time you die. Ironically, this memetically-frustrating music is actually a victory theme from the game it comes from.

It’s hard to gauge the reception to I Wanna Be the Guy with no sales figures or review scores, but its influence was clearly felt far and wide. The Kid appears as an unlockable character in the similarly hard-as-nails indie platformer Super Meat Boy, and the homebrew NES game Battle Kid: Fortress of Peril and its sequel – both excellent in their own right, and even more difficult – were directly inspired by the title. Kayin released two other titles in the series; I Wanna Save the Kids, a Lemmings-esque game based on guiding several defenseless ‘the kids’ safely home, and I Wanna Be the Guy: Gaiden, an official three-level sequel that gives The Kid a grappling hook à la Bionic Commando.

This just barely scratches the surface of I Wanna Be the Guy follow-ups though; there are thousands of fangames made by developers who wanted to put their own spin on the formula, or pay tribute to the games that were most nostalgic to them. I Wanna Be the Boshy is a frequent feature at Games Done Quick events, I Wanna Be the Fangame was developed by ‘Tijitdamijit’, one of the first players to beat I Wanna Be the Guy on Impossible difficulty, I Wanna Run the Marathon was designed to be unveiled for the first time at a marathon that specifically only features I Wanna Be the Guy fangames, and this is just the tip of the iceberg. In other fangames, you can encounter boss battles against Phoenix Wright, Pac-Man, Missingno, Giygas from Earthbound, the Dopefish from Commander Keen, and even a gigantic John Madden who pelts you with footballs.

If you’re worried that you’ve missed the boat on trying the game, a Kayin-endorsed fan-remaster, I Wanna Be the Guy Remastered was released in December 2020, for free, just like the original. Remastered fixed the unintended crashes that the original sometimes suffered, as well as making a few quality-of-life improvements and even adding in a few extra traps to keep familiar players on their toes. As a result, if you’re curious about I Wanna Be the Guy, there has never been a better time to try it for yourself and see exactly how it irritated the hell out of so many players, and why so many of them kept playing. I Wanna Be the Guy doesn’t earn a recommendation for sheer novelty, or for landing its jokes well, but because it remains a uniquely entertaining experience whose influence on indie gaming is still felt to this day.