- King’s Quest: Quest for the Crown

- King’s Quest II: Romancing the Throne

- King’s Quest III: To Heir is Human

- King’s Quest IV: The Perils of Rosella

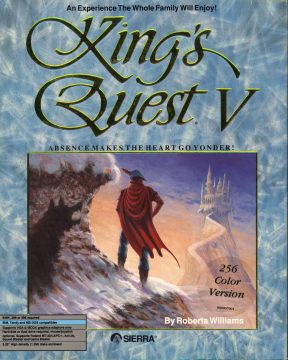

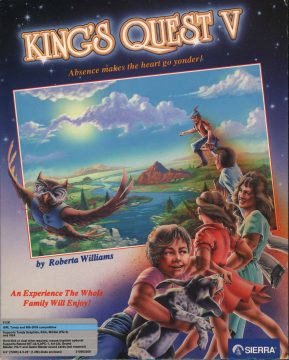

- King’s Quest V: Absence Makes the Heart Go Yonder!

- King’s Quest VI: Heir Today, Gone Tomorrow

- King’s Quest VII: The Princeless Bride

- King’s Quest: Mask of Eternity

- Silver Lining, The

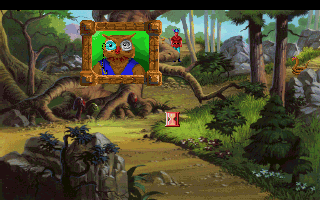

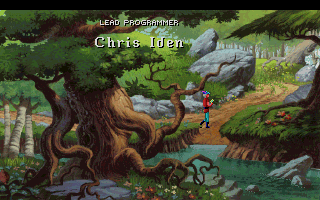

The fifth King’s Quest proved to be a turning point in the development of Sierra adventure games. It’s the first to use their newly developed SCI1 interpreter, which ditches the text input in favor of a fully icon based interface, and utilizes fully painted and scanned 256 color backgrounds. It’s also the first to appear on CD, with fully voice acted dialogue. It also features more cutscenes, in an attempt to further more effective storytelling. But for all of the aesthetic improvements King’s Quest V brings forth, it’s filled to the brim with impossibly frustrating dead ends and illogical puzzles, largely nullifying any of its advancements. The subtitle is a play on the saying “Absence makes the heart grow fonder.”

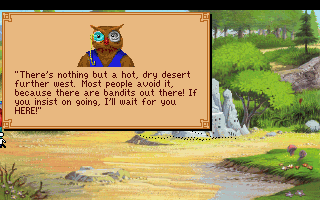

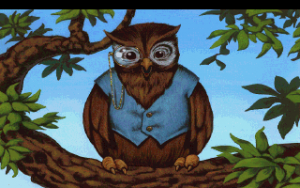

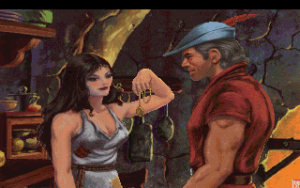

In the introduction, a maniacal wizard appears in front of the Daventry castle and whisks it away in a whirlwind. King Graham, out for a leisurely stroll, is the only one spared and is stunned to find not only his house but his family entirely missing. A friendly owl, the familiar of an elderly wizard named Crispin, relates the tale. He then brings Graham to the kingdom of Serenia (the same land, at least in name, as in Wizard and The Princess) to begin his quest. Eventually Graham learns that the culprit is the evil magician Mordack, who just happens to be the brother of Manannan, the wizard who had imprisoned Alexander in his youth, and was turned into a cat back in King’s Quest III. Neither wizard is pleased with the situation, and seeing how Alexander can’t reverse the spell, they seek vengeance on the Graham clan instead.

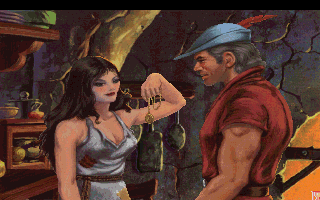

King’s Quest V is structured a bit differently from its predecessors. The land of Serena is still relatively non-linear, featuring a town center, an enchanted forest, and a desert. There are more people to talk to and interact with, all of whom need aid in some way or another. There’s a colony of ants under attack by a dog, a hive of bees under attack by a bear, a moping prince looking for his love, and a group of bandits out in the desert who open the door to their stash, predictably, with a good old fashioned “Open Sesame”. Except for the frustrating desert maze, where too many steps in the wrong direction without a source of water results in death, each screen has a purpose, and there’s much less aimless wandering, as the land no longer loops infinitely. Combined with its enhanced interface, it seems to have left behind some of its old school conventions in favor of something more modern.

The only path out of Serenia is guarded by a poisonous snake – perhaps a reference to the first task in Wizard and the Princess – so much of the first segment consists of running tasks that eventually lead to the item you need to get past. This in itself feels rather artificial – hours of exploration just to eliminate a mere reptile? – but that’s really the least of the game’s concerns. King’s Quest V is absolutely filled with situations where you can get yourself impossibly stuck. These have always existed up until this point in Sierra’s library, but rarely are they so unrelenting as this.

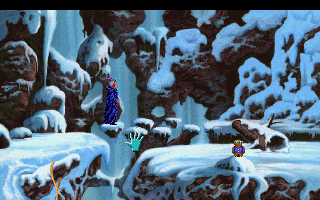

Shortly into your quest you’ll find a rat being chased by a cat. In the span of a couple of seconds, you need to toss a boot at them, thereby saving the rat from becoming a meal. This might not seem like an important event, but you’ll pay for it a little while later, when you’re kidnapped and stuck in a basement. If you saved the rat he’ll untie your bonds, but if not… Oh well! When you enter a temple, you’re only given a few seconds to get in, grab the stuff you need and get out before the door closes, trapping you inside. One item is obvious, the other is a mere pixel in size. You can only open that door once, so if you leave without grabbing it, it’s gone for good. After you leave Serenia, you must climb through a series of snowy mountains and cross a small lake until you get to Mordack’s castle. This section is far more linear than the first part of the game, but it also requires that you’ve picked up everything from earlier on. If you’ve missed a single one… well, after a certain point you can’t go back to retrieve any of them.

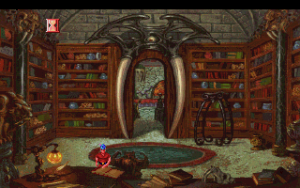

Perhaps the most aggravating instance involves a pie you get from a baker. If you eat it, it’s gone forever. When crossing the mountains, you’re told that Graham is hungry, so eating the pie seems logical, right? Or when you find a starving eagle, the pie might seem like a good choice? The game lets you take both of these courses of action, but they both make the game unwinnable. You’re meant to munch on a leg of lamb which you hopefully stole from the inn while being kidnapped earlier on. Instead, you’re supposed to save the pie in order to (get this) throw it in the face of a ferocious yeti, besting him Three Stooges-style. Solving this particular puzzle is rather comical, but the multiple ways the game sets you up to fail is just remarkably cruel. Walking around Mordack’s castle is hair-pulling, because he can randomly transport around and kill you, without recourse. There’s the usual maze sequence, made more frustrating because the viewpoint changes when Graham walks in a different direction, making it more disorienting than it needs to be.

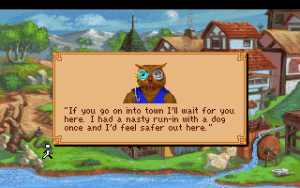

And then there’s Cedric the owl. He accompanies you through most of the game, and was probably meant to act as a foil for Graham, providing some accompaniment or at the very least some comic relief, but he only succeeds in being both incredibly useless and astoundingly annoying. He abstains from following you into dangerous situations, excusing himself for his wussiness. He doesn’t offer any useful advice, outside of warning Graham to “look out!” when it’s entirely too late to prevent anything. The absolute best – or worst, attitude depending – is when you get into a boat and sail out into a lake. A short way into your journey, Cedric remarks “Watch out, there’s a hole in the boat”, wherein you both immediately sink and die. You were supposed to have realized there was a hole, even though the game never tells you this until you sink, and patch it up before you set off. (This might also be another reference to Wizard and the Princess, where you need to make a similar journey and patch up a boat with a blanket, although at least that game was kind enough to let you know beforehand!) Cedric also manages to get in trouble no less than twice, and while it’s mandatory to save him the first time, you can leave him for dead the second time around. However tempting this may be, it also prevents you from winning the game, because the finale is the only – ONLY – time he does anything useful, and even then it’s unintentional.

Cedric’s pointless interjections aren’t a huge issue in the disk version, where the text boxes can be clicked away without much thought. They are maddening in the CD version though, since Cedric’s voice is spoken by a man in an extraordinarily high pitched voice with some horrifyingly unidentifiable accent. His constant scolding, meaningless warnings, perpetual whining and more-obnoxious-than-usual puns are just about enough to earn him the honor as being one of the worst characters in all of adventure gaming. But to be fair, it’s not like the rest of the voice acting is much better. With all of the money Sierra sunk into the artwork and CD-ROM technology, they neglected to allocate any funds for actual voice acting, instead relying entirely on regular staff members around the office. Not all of them are terrible – writer Josh Mandel takes on the role of Graham and does an alright job – but even at their best moments most of it sounds quite amateurish. All of the recording seems to have happened in a bathroom, with each voice sample possessing a distinguishable echo, which is further exacerbated by the extreme audio downsampling. And then there are all of the talking animal characters (Beetrice the Queen Bee, King Antony the Ant) whose voices are run through modulations, making them almost impossible to understand. There’s not even an option to disable voice acting in favor of text in the CD-ROM version, forcing all of the pain on you.

You could play the disk version, but even that has issues. At various points throughout the adventure you’re given copy protection quizzes, proclaiming that Graham has become weak and needs magic to be recharged. These are sudden, persistent, and annoying. Its interface is also overly busy, containing two different walk icons. The standard “Walk” action is much like the one in the older SCI games – that is, you’ll walk in a straight line, but if there’s anything that gets in the way, you’ll stop. The “Travel” icon features actual pathfinding, so you’ll walk around any obstacles to your destination, rendering the other one almost completely obsolete. The “Save” and “Quit” options are also present on the main item bar. In the CD-ROM version, the first “Walk” was removed, and all of the game management functions were condensed into a single secondary screen, which Sierra used for all of its successive SCI games. The CD version also changes some of the death quips, for some reason or another.

There’s no doubt that King’s Quest V brings a lot to the table, as the background artwork is really quite excellent, and the full screen cutscenes were leagues ahead of anything else released in 1990. The interface is substantially more user-friendly, and areas that probably would’ve been arcade sequences if done in the older games – navigating the mountain paths, for one – barely require any effort here, and the game’s much better off for it. But, like KQIV, for all of the effort put into storytelling, the actual plot is only passable, and the characters only exist briefly to present puzzles, give you new items and move on. Combined with the overtly frustrating design, King’s Quest V is a game that, despite its popularity at the time, has aged quite poorly.

King’s Quest V was released for the PC, Macintosh, Amiga and FM Towns computers. The PC version supports EGA graphics, although it dithers the backgrounds so much to almost totally ruin their impact. Other than some differences in color palette, most of these versions are the same, although the CD-ROM version is only available on the PC.

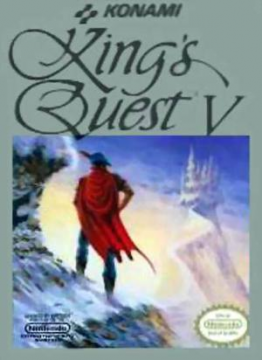

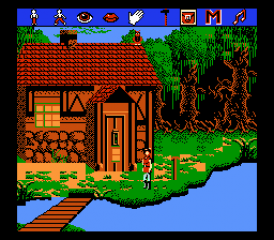

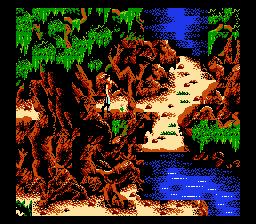

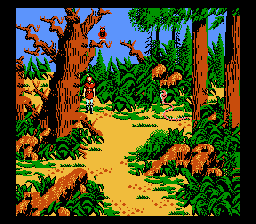

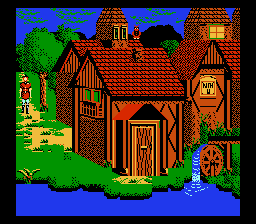

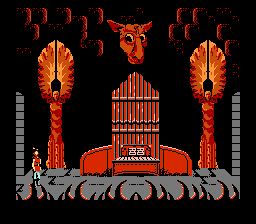

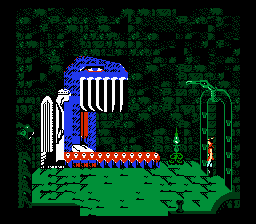

Beyond the computer version, it was also ported to the Nintendo Entertainment System. The development duties were handled by Novotrade, and the game was published in North America by Konami. The NES saw successful ports on a few adventure games, like LucasArts’ Maniac Mansion and ICOM’s Shadowgate, but those were both fairly old games at the time, and the NES could easily handle them. On the other hand, King’s Quest V is substantially more advanced and a lot needed to be cut back, both in order to fit the system’s visual limitations and its ROM size. The disk version is nearly 9 megabytes – the NES version is almost 5% of that, with a mere 512k (or 0.5 megabytes) of space.

The size and color depth of the backgrounds were simply not going to work on the NES at all, so they were completely redrawn. They all look horrendous. Each is constructed out of several small tiles, per most 8-bit console games, rather than single bitmaps, and nearly every one looks like a terribly glitchy mess. The color choices are also poor, reducing what was previously a gorgeous game to a total artistic disaster, sometimes almost comically so. In some areas, the clouds are actually green! The full screen cinemas are gone, reduced entirely to text, rendered in the old system font that the AGI-era Sierra games used. Most of the important text remains, although some flavor text is gone, and certain parts are abridged slightly. The two movement options serve a point here – the first “Walk” icon will allow you control Graham directly, while the second will allow you to point-and-click. Looking at or interacting with items is also handled through the cursor, but it’s extremely slow, and almost painful to use. There’s almost no music at all either, barring some bits of incidental music. It’s a painful game to play, not counting all of the other design issues it inherits from the PC version, and exists only to be mocked or feared.