It’s common to see games take on reputations more concerned with the idea the game represents than with its actual substance. Regardless of whether or not these reputations are correct, it’s easy to understand why that happens. People don’t have the time to play every game that’s out there, and many wouldn’t be interested even if they did.

For as much as this simplification benefits players, it’s hard to think of games that benefit from their negative reputation. Surprisingly, Hiza no Ue no Partner: Kitty on Your Lap, published by Kaneko, is one such game. In the West, the premise of a catgirl dating sim, combined with the lack of knowledge of/interest in anything beyond that premise, has given Kitty on your Lap a reputation of being perverted. Although there’s a small grain of truth to that sentiment, looking at the circumstances surrounding the game’s creation paints a more interesting picture. It was first sold for 5800 yen, signalling the game as by far the biggest and most notable release from a developer known for smaller budget releases. Notable seiyuu were brought on to voice the characters, and the game became something of a small franchise, with a radio drama and a bonus gaiden disc released shortly after the game itself.

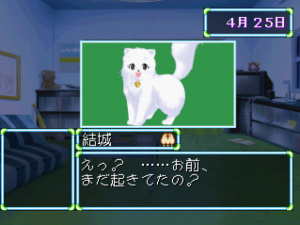

One needn’t play the game for very long to see the game somewhat lacks substance. After naming the protagonist, he goes on to relate his life story. A loner attending his first year at college, he lives by himself and doesn’t have many friends. This changes one April night when he finds three cats on the roadside and decides to adopt one. After a strange dream where an old man explains the task he has been entrusted with, the protagonist wakes up to find his cat transformed into an infant catgirl. From this point forward he must, on top of managing his classes and what little social life he has, spend the next year raising his feline daughter in the hopes that she’ll become a real human when she grows up.

Note: Although the protagonist is a cipher you’re encouraged to name from the start, his default name is Kouichi Murakami (村上 功一).

Characters

Yuki

Although described as an ojousama, Yuki is better described as a traditionally feminine imouto. She’s soft, demure, and often tends to duties around the house in an attempt to impress Kouichi. Because of this she also comes across as the most responsible of the three female protagonists. Voiced by Junko Iwao.

Mimi

Mimi is a kind of middle ground between Yuki and Lena, combining the former’s femininity with the latter’s energetic personality. The result is a somewhat more childish but also more active character than the others. Her speech (in both forms) is more forceful; she’s more likely to take part in physical activities; and she’s something of an otaku, spending her free time reading Shounen Jump or playing video games. Voiced by Yuko Miyamura.

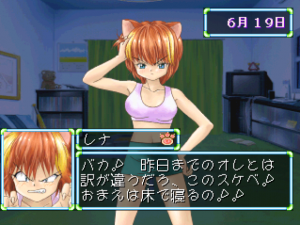

Lena

A tomboy through the lens of a tsundere, Lena’s relationship with Kouichi is prone to fluctuation. Although she genuinely cares for him like the others, she also doesn’t want him to know about those feelings, frequently putting herself on the defensive to deny them. Strangely, she’s also the only catgirl born with her own pair of clothes. Voiced by Yuka Imai.

Kobayashi

A college classmate and one of Kouichi’s only friends, the role Kobayashi serves is more important than his character. He wants to start a career making movies, but outside a student film festival, this point rarely comes up. He also has a crush on (and in some routes dates) Juri. And although it rarely comes up, he owns one of the other catgirls that neither Kouichi nor Tomoka do: Mimi if you chose Yuki, Lena if you chose Mimi, and Yuki if you chose Lena. For the most part, though, Kobayashi is there either to help the protagonist with his current problems or to get him into minor bits of trouble, especially romantically. Voiced by Nobutoshi Canna.

Tomoka

An old childhood friend Kouichi hasn’t seen until college. Outside the three catgirls, Tomoka is the only other character available to Kouichi romantically. Although tomboyish as a kid, in the present her personality is closer to Yuki’s, acting like a big sister especially around the catgirls. Voiced by Miki Nagasawa.

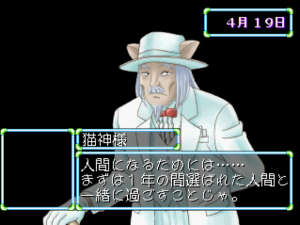

The Cat God

More or less the Blue Fairy equivalent in Kitty on your Lap’s Pinocchio-esque story. Although a considerably more capable parent than Kouichi – emotionally supportive, capable of approaching the girls as equals, but providing necessary guidance – he prefers to leave them in the protagonist’s care to better facilitate their becoming human. He also provides the narration for system messages like saving or confirming choices. Voiced by Kenichi Ogata.

Kaim

Kaim is the closest thing the game has to an antagonist. By day a black cat renowned for fending off evil spirits in town, he can become a human like the three catgirls. Unlike them, though, his opinions of humanity are far more negative. He believes the inequalities between cats and humans make any bonds between them false, and that humans will throw away or commit violence against cats once those bonds break down. Although he introduces conflict into each route by telling the catgirls his feelings, it’s all but stated that those feelings are genuine on his front. In fact, some of the bad/neutral endings (where Kouichi abandons his daughter) depict him as a genuinely caring boyfriend. Voiced by Hikaru Midorikawa.

Juri

If the Cat God is the game’s father equivalent, then Juri is its mother equivalent. A local veterinarian who knows the catgirls’ secret, she prefers to let Kouichi handle things how he sees fit. Meanwhile, she’ll reassure him and his daughter while encouraging both to do their best. Voiced by Emi Shinohara.

Kaoru Kotani

Although not the only friend the catgirls have (they mention a few cats here and there), Kaoru is the only one to be given any real characterization. A high school student who works at the local convenience store, she’s a friendly person willing to hang out with the catgirls or talk to Kouichi every now and then. Voiced by Hiroko Konishi.

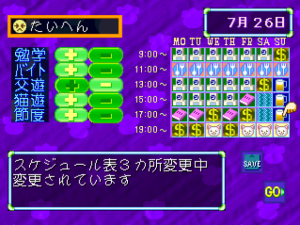

The first thing to note about this premise is how heavily constructed it is to achieve a certain effect. Each plot beat or character trait signals Kitty on your Lap as a game steeped in dating/raising sim convention, and play is more than willing to oblige. There are two sides to play, both of them very similar and reducing to directly managing statistics. One side, rooted in dating sims, sees you managing Kouichi’s numbers. You decide which activities he will perform in a given week in the hopes they will raise his stats and allow him to better provide for his daughter. The other side, stemming from raising sims, applies that same logic to his daughter. Here, the player chooses activities that will raise her humanity while reducing her feline characteristics.

A generous reading would see these structures as building on the genres they work with while articulating the game’s larger themes. Embedded in the narrative’s premises are ideas about self-betterment, whether it’s the protagonist’s need to become a more well rounded person or the catgirls’ quest to become human. Such a goal is portrayed as worthy of pursuit in its own right, but also as highly personal. Characters don’t advance toward a single ideal as much as they grow into the person they already are. By highly personalizing the tasks available to a given character and giving those tasks no goal outside that character’s well being, the two sides of Kitty on your Lap faithfully represent that point.

At the same time, by connecting those sides together in certain areas – how (much) the catgirl’s stats change seems to depend on Kouichi’s stats, and Kouichi can only raise his own by caring for and loving his daughter – the game better articulates its own narrative premise. One cannot become their ideal self on their own, it seems to argue. One always requires another person, both for emotional support and to challenge one’s self to be better than they already are.

Such a reading assumes a lot on the game’s part; mostly that its project is thematic in nature. However, one can easily repudiate that assumption. So far Kitty on your Lap’s accomplishments have more to do with the genre it inhabits than with its own efforts, and looking at the latter, one gets the impression that it doesn’t realize that video game mechanics can be used expressively. In spite of any ideals about self-betterment, most playthroughs see Kouichi absolutely miserable: he can spend weeks at a time sick from stress, either missing school/work/etc. or going through the motions. The narrative never seems to acknowledge his ailments, and the actual mechanics of play breeze right through the daily life they theoretically value. With a few exceptions, the player only sees that life as events on a calendar; as minor blips and as rolls of the dice, as though Kouichi has little control over his own life.

The truth of the matter is Kitty on your Lap is exactly what it appears to be at the surface. More specifically, the game directs all of its creative energy toward situating itself within the popular anime trends from that time. Each character, for example, exists less as an individual and more as a collection of appealing anime tropes. This is especially true of the catgirls, whose personality traits both align them within a given archetype and make them desirable romantic partners for the presumably male player. (This would explain why the catgirls are indistinguishable during play; Yuki will respond to watching TV the same as Mimi or Lena would.) And the larger narrative, lacking characters to explore and only possessing themes that dating sim convention has imposed on it, resigns itself to being a loose assortment of daily experiences for the player to participate in and not much else.

It’s difficult to deny that, on the narrow terms the game has given itself, Kitty on your Lap finds the success it was looking for. Still, one wonders if the sacrifices it had to make to achieve that are justified. The game’s methods are destructive in nature; they eliminate anything that might lend it substance without providing any substitutes. As far as Kitty on your Lap is concerned, that destruction is justified. Such a straightforward approach allows it more direct access to the anime conventions it wishes to pursue. Adding nuance would only complicate the process, the game reasons.

What it doesn’t seem to realize is that anime tropes and nuance can exist alongside each other, and that the latter can strengthen the former by elaborating on it or grounding it in something more substantial than itself. In practice, then, all Kitty on your Lap’s efforts accomplish is to deprive the game of anything that might lend it charisma, leaving behind only an eerie emptiness. The decision to limit the characters to what players see of them at the surface (more specifically, to how they relate to the immediate situation) may facilitate their performance of the anime archetype assigned to them, but it also results in their characters lacking depth. Yuki is completely exteriorized, and Kouichi completely lacks a presence.

Likewise, because the world is made specifically for the player’s enjoyment of it within the moment, the game will not allow those moments to build up to something more. When Kouichi’s landlady threatens him with eviction for violating her no pets policy, he proceeds with his studies/work/life just as smoothly as he did the day before. The same holds true when his cat runs away to spare him the possibility of ending up on the street. In the end, the conflict is resolved not through any change to the characters or their relationships, or to how they change their lives, but through magic: the Cat God appears to the landlady in her dreams and cures her of her allergies, the source of her policy.

Although this plot point occurs in the third act, it speaks to a format affecting the entire narrative. The plot deprives moments of any dramatic weight, and the world at large remains suspended in an eerie stasis; prevented from threatening the player with change. Kitty on your Lap’s cheerful facade betrays a nihilistic core, fueled by an embrace of pop culture tropes made to be shallow and an idealized vision of everyday life as lacking any greater meaning.

The closest Kitty on your Lap comes to having any substance, and the last possible defense one can muster in its favor, is the historical value it holds. One could read the game not as a straight embodiment of anime conventions, but as a parody of them; one meant to demonstrate how empty and absurd those conventions can be. A strained reading, but if true, it would make Kitty on your Lap an esoteric predecessor to later absurdist visual novels like PacaPlus, Creature Comforts, and especially Hatoful Boyfriend. Unfortunately, that reading doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. Bereft of the self-awareness and willingness to play with convention and form that would exemplify these later games, Kitty on your Lap becomes the exact sort of game it might lampoon.

While sales numbers for the game are impossible to come by, circumstantial evidence suggests it was among Kaneko’s more successful games. Even ignoring the supplementary material, the game sold enough to warrant a budget re-release a year after it originally came to market. Unfortunately, the success was short lived and the game was quickly forgotten. All that’s left of the game today is what people have made of it: the reputations, a scattering of videos, the small catgirl fandoms that have formed around it, and the use of “Kitty on your Lap” as a Hello World substitute, for some reason. In many ways, this is a logical conclusion to the game’s desires. What would be more appropriate for a game driven to capitalize on the zeitgeist than to melt away into the crowd?

Links

Kitty on your Lap Mixi community