- Last Armageddon

- After Armageddon Gaiden

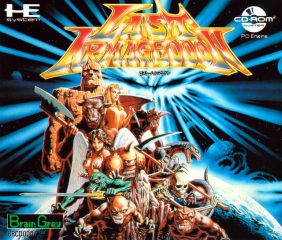

Last Armageddon is an infamously player-unfriendly RPG for Japanese PCs, released by a new developer trying to subvert the Dragon Quest template for JRPGs. Gone are towns and NPCs, gone are the virtuous heroes and their quests. You lead the heads of twelve tribes of unruly demons through a post-apocalyptic hellscape, battling against aliens and their army of bio-robots for dominion over the Earth. All the while, you explore the ruins of human civilization in search of clues about what caused the apocalypse. It’s hard to imagine a cooler concept, but the game is riddled with cruel design decisions, unclear directions, and hilariously uneven pacing that make it less than an ideal play experience.

Last Armageddon was the most ambitious release by Brain Grey, designed and written by Iijima Takiya. Iijima left after its release to become the head of developer Pandora Box, where he’d work on further RPGs like Burai and Alshark, and eventually another game in the Last Armageddon universe. Today Iijima is probably best known for his horror writing, from the Apathy visual novels to the paper novels he continues to write today.

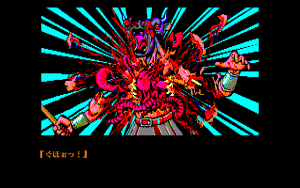

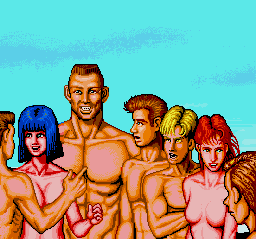

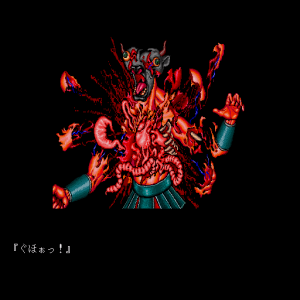

No one has any complaints about the way Last Armageddon introduces itself. A monster scout, the Minotaur, is brutally dismembered not a minute into the game’s opening cinematic, then the game’s 80’s hair metal logo pops up over an appropriately heavy synth riff. You’re then taken to a feast in hell of all the monsters in your party, who view the dismemberment of their comrade through the skeleton’s eye, which apparently functions as a projector. The Gargoyle becomes possessed by a tubular alien parasite which burrows from his chest into his brain, and delivers an ultimatum from the aliens, who claim dominion over the planet. The monsters respond by tearing out the parasite, spilling copious gore. As the monsters return immediately to their meal, they argue about the best course of action before setting out to the surface.

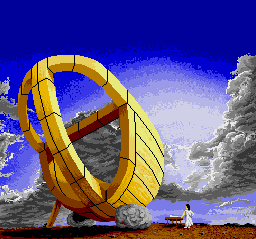

With an intro of that caliber, what follows is strange and disappointing. You’re dropped into a dull world of greys and browns, within a circle of lithographs scattered upon the ground around you, at the entrance to Hell. Each numbered lithograph offers a cryptic, laconic hint at the nature of the world and its inhabitants. As you venture beyond the circle, you find more lithographs, and you start to find random encounters as well, which will likely kill you in a round or two until you’ve leveled up a bit.

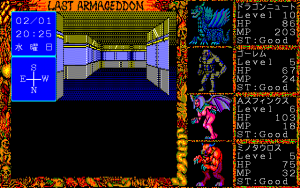

The game has a calendar and clock system, and moving or opening the menu advances the clock. During the day, you control the Day Party of monsters, and likewise for the Night Party. You control a third party, the “Salvan Day of Crushing” Party, on the so-named last day of each month, a extra-long day of killer sandstorms.

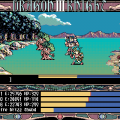

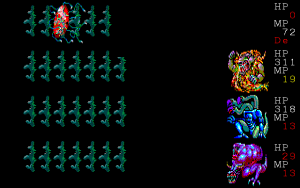

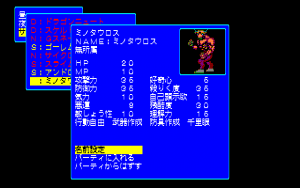

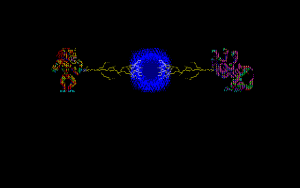

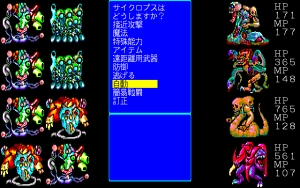

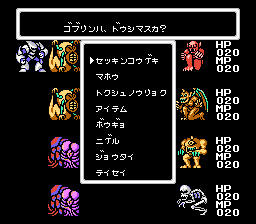

Battles are fairly standard JRPG fare, towards the bottom of the stack in terms of visual presentation. Each battle is unbearably slow by default, though there is an in-game speed setting that can make them marginally more tolerable. Each monster has a variety of actions to take, at least: in addition to normal attacks and the usual kinds of spells, your monsters usually have a set of Special Abilities, which are often either near-useless or game-breakingly-powerful, and cost no MP. One infamous quirk is that when a monster defends, they nullify all damage rather than merely reduce it. As a result, if you defend with three monsters and attack with one, each enemy attack has a 75% chance of accomplishing nothing. It’s dreadfully boring, but it’s a legitimate strategy for survival.

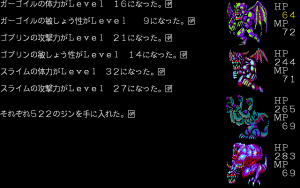

Leveling up has some complexity to it, if still quite grindy. Each of your monsters’ stats are leveled up individually through different actions in battle. You increase Defense by defending, Magical Strength by using spells, and so forth. Each spell also has its own individual level too, contributing to learning future spells. It is quite a bit like Final Fantasy II, but was released a few months earlier, and is even easier to exploit. Grinding Defense is very easy, since Defend nullifies all damage, so grinding it for a few tedious hours at the beginning of the game can mean never taking damage for the rest of the game.

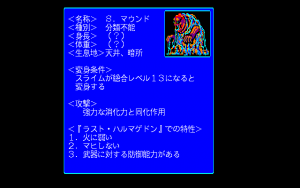

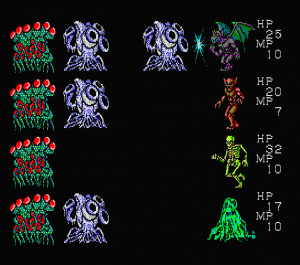

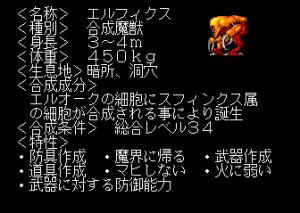

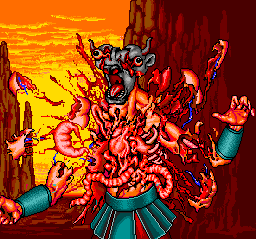

Once a monster reaches a certain level, they transform into a stronger and more terrifying form. They transform three times on their own, but for the last two transformations, things get interesting – you can combine their genes with another one of your monsters, out of 2-3 choices. Not only does the resulting creature usually look scarier, but it also possesses the abilities, skills, and spells of both creatures. With a bit of planning, you can distribute characteristics like the Slime’s physical resistance to weaker monsters who need it, or give the G-Snake the ability to equip weapons and armor, making it even more of a powerhouse.

While the rest of the game is top-down, the game’s dungeons are explored in first-person. The dungeons are completely featureless grid-based labyrinths, where the stairs and the crucial event triggers are invisible, and random encounters every few steps throw off your ability to navigate. Some of the monsters have an ability to display a map from what you’ve seen so far, so you won’t be completely lost, but the core experience of the dungeons is still just confused wandering in search of a magical invisible tile that triggers a cutscene. Later dungeons introduce such delightful new offerings as false walls and invisible teleportation tiles.

The barren world doesn’t feature any towns to shop in. Instead, some monsters have skills that allow them to create items, weapons, or armor. Defeating enemies earns a currency called Jin, which is spent on crafting items and equipment. So, the crafting interface is basically a shop menu, but you can access needed items in the middle of a dungeon, which removes the need to prepare yourself for dungeon crawls.

After a few dungeons, you’ll open the way to the Tower of No Return. But at the entrance, you’ll discover that you need to view all 108 lithographs in order to enter the tower. There’s no in-game checklist, so hopefully you’ve been keeping track of which ones you’ve seen this whole time! This is one of the only design decisions in the game deemed so regrettable that it was softened in a later release – the PCE CD version requires you to visit only 12 particular red lithographs, thankfully.

Once you’ve finally gained entry, the Tower of No Return is a long and tedious seven-floor maze, but it rewards your progress by beginning to reveal the story of humanity’s demise. Each floor gives a particularly dark interpretation of a religious or historical person’s story, and uses it to illustrate the birth of a new human vice. Greed came about when Noah, warned of the flood, keeps his ark secret from his neighbors and family to ensure he has enough wood to build one himself. He only begrudgingly lets his family aboard, and brings the animals solely for food.

The tower’s story reaches a conclusion that only leads to further questions. Humans were almost wiped out in 1999 by monsters, but some survived. They turned their minds to drama, dreaming up 12 tribes of monsters in order to watch them be destroyed by angels. Why would the humans create monsters just to destroy them? And does this mean humans are still alive? The monsters are filled with fear, a new emotion for them.

A less ambiguous revelation is that the top of the tower is actually an entrance to the Overworld, an entirely new map where the second half of the game takes place. This is the surface of the Earth, the human world, with dungeons like a Hospital and Police Station. After learning that humans are still alive in a place called the Fantasy Land, you must “awaken the seeds of humanity” in each monster so they may enter. The Fantasy Land has an “empathy sensor” at the entrance to enforce this requirement, which is pretty hilarious.

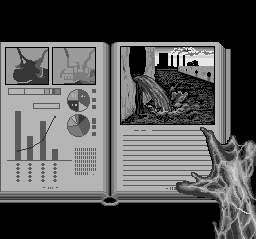

As you explore these remnants of the human world, you must find a specific artifact that helps each monster understand why humans would create monsters. The Golem finds a clay idol, evidence of humans trying to make humans with their own hands, and feels the despair at their learning they did not create themselves. He learns pity for the humans this way. The Slime finds a book warning of industrial waste, particularly sludge in the ocean, which he really identifies with. He recognizes with horror that the humans created something harmful in order to develop further.

It’s a particularly interesting and touching part of the game, but it also involves a lot of worrying about which monsters are in your party when you visit particular dungeons. Most egregiously, the artifacts of the default Salvan Day Party are spread across several dungeons, which means you’ll have to rush all over the map to try to do them all in one day, or otherwise need to kill significant amounts of time waiting for the next Salvan Day to begin.

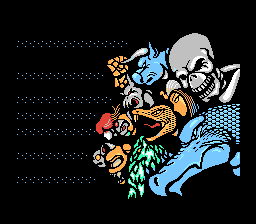

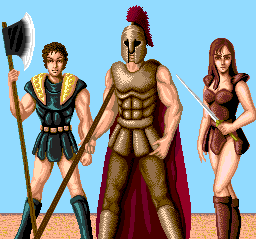

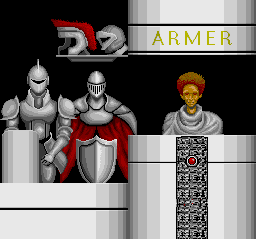

You finally enter the Fantasy Land, a parody of the traditional high fantasy RPG conventions rejected by the rest of the game. You battle against fighters, wizards, and clerics, and you can visit weapon and armor shops, though they don’t have anything to sell you. Once a monster in your party decapitates one of these humans (as they do to anything they don’t understand), you discover they’re all just robots, part of a LARPing simulation run by a computer for the amusement of the bygone humans. The Minotaur is flabbergasted that humans would enjoy such a thing as a fantasy RPG:

“Fantasy!? Is this the fantasy of the humans, to spend routine days repeating simple actions?”

After 20+ hours of wandering through dungeons and button-mashing through random battles, this is a pretty amusing and cruel line to read.

After decapitating the “King” of Fantasy Land who gives out quests, and defeating the computer running the simulation, the computer remarks that the monsters seem just like humans, and it sends them off to the final dungeon, the Control Tower. This dungeon is fairly short and more of the same, and upon reaching the end, the monsters enter a mysterious light. The alien from the opening sequence reveals that this was all a simulation designed to remind humans of the qualities they have lost during their evolution as a species, and to warn them against continuing on their current path. The monsters look in amazement at their restored human bodies, and the restored Earth, a green and blue Eden once again.

There’s a lot to complain about, but Last Armageddon clearly found an audience. Its sales on MSX2 and PC-88 far exceeded expectations, selling out its initial run on the release day. These sales funded the ports to all the other platforms. This probably isn’t that surprising – it seems like a very easy game to market. And while the game is generally trashed on English-language sites, it is remembered quite fondly on Japanese sites, called a “masterpiece” on a few of them. Clearly understanding the dialogue is key to the game’s appeal, and Japanese players may be more enthusiastic about dungeon crawling, as is clear from the Japanese popularity of Wizardry.

As mentioned, Last Armageddon saw quite a few releases. The original game, released across the MSX2, PC-88, X1, and later PC-98, plays identically across all platforms. There are some significant differences in load time and text clarity, as well as various changes to the screen frame and cutscene graphics.

The later X68000 and FM Towns releases offer higher resolution and more color, as well as remixed music and voice-acted cut scenes. Additionally, about 40 of the final-stage monsters were redesigned entirely, for the future releases as well. The new designs are almost all better, more varied, and more menacing, but they don’t show much resemblance to the original monsters that went into them.

The next release for the PC Engine CD is considered the best. Most noticeably, all the first-person dungeons are replaced with top-down ones and given more sensible layouts, with graphics to help distinguish different areas. The game also has bosses now, where the PC versions simply had random encounters or nothing, which helps the game’s pacing a bit more. And its music is the best, featuring the remixed soundtrack along with entirely new tracks, like the classical-inspired synth battle theme, previously highlighted on this site.

The final release for the Famicom was outsourced to Advance Communication Company, developers of the infamous Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. That said, it’s an extremely faithful port, keeping the full first-person dungeons from the PC versions and the bosses of the PCE CD version. But hardware limitations mean the dialogue is very concise, and more than half the monsters were cut from this version. And worst of all, battling and moving around are incredibly slow, making the game even more of a slog than before. Finally, the music is totally different and rather less appealing, sporting influences from surf rock and atonal bass drone.

Though it’s the worst version of the game, the Famicom one is the only one with a “fan translation.” A caveat: it’s clearly the product of a machine translation, and the results range from silly to maddeningly unreadable.

Version Comparison:

Monster Design Highlights:

Links:

The Brothers Duomazov – review and concise walkthrough.

Bogleech – review of monster designs.

Inconsolable – review and brief playthrough of the machine-translated Famicom version.

Romhacking.net – machine translation patch for the Famicom version.

Masaoki Satou’s Homepage (JP) – most of the MSX2 version’s text, illustrated with screenshots.

Tower of Retro Game (JP) – detailed playthrough with commentary of the PCE version.

4Gamer (JP) – Interview with Iijima Takiya, spanning most of his career.