Japanese Arcade Flyer

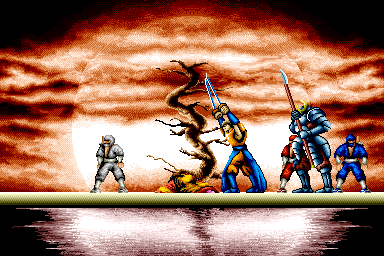

In the intro to Ken-Go (no connection to the later Lightweight-developed series), a fleeing woman collapses in front of a lone, dead tree, before men with swords and pikes catch up and cut her down. The hero, Blue Dragon, arrives just in time to deflect a few shuriken coming his way, before the killers flee in turn. He kneels briefly before the woman – Princess Orchid, according to the flyer – and gives chase.

It’s like a more violent take on Double Dragon’s iconic intro.

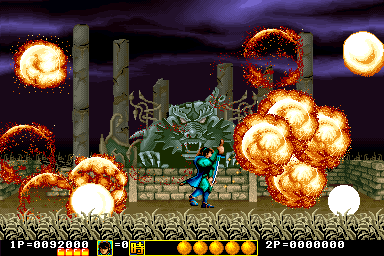

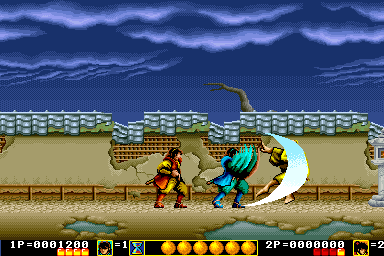

The story, then, is not about rescuing a princess, but about avenging her. As with any other arcade title, it mostly exists to justify the setting; in this case, a dark, slightly fantastic Japan, in the year 1600. What the game is really about, though, is holding the action button to both block enemy attacks and charge up your own, before releasing them at the right moment. The longer you do, the further they go, and the more damage they do. That is the central mechanic around which the game is built.

The right moment.

It is one of a few games bearing the Irem name that can be attributed to Nanao’s internal software development team, rather than Irem itself. That story is a complicated one, but it can be summarized as such: in the late ’70s, when Irem decided to get into game development, it partnered up with a company called Nanao Denki, which specialized in manufacturing CRT screens. The partnership was both financial and practical, as Nanao would build the screens used in Irem’s arcade cabinets. After a few years, however, Nanao took over Irem, eventually ousting its founder, Kenzo Tsujimoto, who’d go on to find much greater success with his next company, Capcom.

An artist’s representation of Tsujimoto’s treatment at Irem.

From that point in the early ’80s up until about a decade later, Nanao owned three game studios: Irem proper, which specialized in arcade games, particularly shoot-’em-ups; Tamtex, which developed most of their NES and Game Boy games; and their own internal software team, which also made arcade games, though at a far less prolific rate. All games were published and marketed by Irem, and while the Tamtex name managed to get out a bit, Nanao’s only ever did in a select few interviews with game magazines. We know from the pseudonyms they used in ending credits and score entry screens that they were responsible for games like Kickle Cubicle, Ken-Go, and, more famously, R-Type Leo.

The developers snuck in their nicknames and company’s name in the high score table.

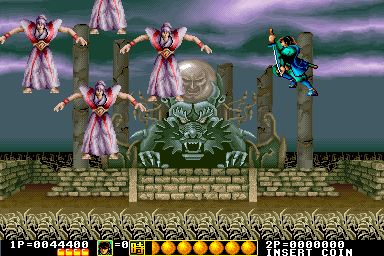

Their games were noticeably more colorful than Irem’s, though not necessarily lighthearted or cute. Ken-Go is probably the darkest thing they’ve done, but the rich reds and blues of its color palette are entire aesthetics away from the gritty, rusty grays and browns of Irem’s R-Type, In The Hunt or GunForce II. Most impressive are their skies, which layer clouds and sun rays to set various moods, while making use of dithering to create a foggy effect when filtered through the scanlines of CRT screens.

Their design philosophy was also much more forgiving and player-friendly. Ken-Go‘s controls may need a period of adaptation, but it’s no quarter-muncher. You can take four standard hits before you die, and there are power-ups that increase your maximum health (though just for that one life). Some parts are tricky, especially in single-player, but the game can be beaten with just a few credits with a bit of practice. It’s got a two-player mode, too, and as is often the case, two reasonably skilled players can really dominate the game.

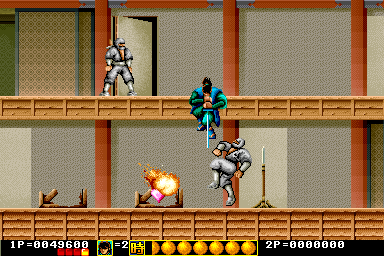

Red Dragon joins his brother Blue Dragon for a two-player run.

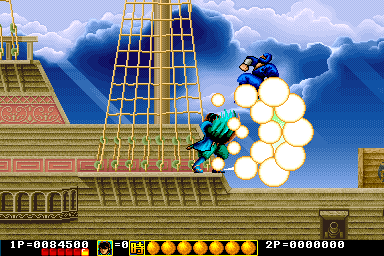

Because you ordinarily move around while holding the block/charge button, jumping is done by pressing Up, like in fighting games. This is awkward, but luckily the game doesn’t really involve much platforming, apart from the ledges you can get on and off of to get at enemies or win a bit of time to charge up a more powerful attack. There is a very clumsy moment later on where the game expects you to hop on a galloping horse to get past a section of burning ground, but thankfully, that’s about it for the really bad parts. Most of the time, jumping is used in combat, both as an evasive move and to throw projectiles high up into some boss’s face. You can also bounce off the left side of the screen for a super jump, but it’s pretty difficult to pull off, and hardly necessary. Finally, you can press Down while airborne for a landing attack, which does come in handy.

Standard sword strikes are possible, too, but here they serve a secondary function – clearing the screen of a few weaker foes, or getting a few quick hits in.

Standard sword strikes are possible, too, but here they serve a secondary function – clearing the screen of a few weaker foes, or getting a few quick hits in.

While the flow of the gameplay is more defensive and methodical than in the usual arcade side-scroller, this is still a quick game, as the levels are short, and there are only five. Thematically, they stick to creepy landscapes and Japanese castles, with the exception of one level where you briefly board a ship before going through a cave. The enemies are mostly human, but most of the bosses use some kind of magic. Those battles are typically straightforward, revolving around finding the right timing to release a blast in between blocking or dodging everything they throw at you. Mid-bosses usually drop sword power-ups that increase your attack power; there are also healing items, and others that increase your score or the time limit for the current level. Said limits are not so tight that you need to rush, but tight enough that you should keep it moving.

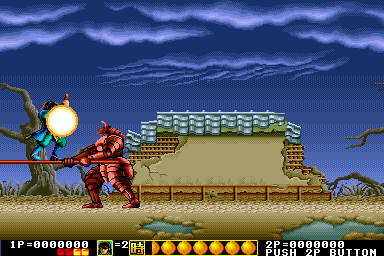

There is a slightly unpolished feel that comes up during certain moments of the game. Bumping into another sprite only produces a knockback effect when you’re blocking, and things can get a little messy when you’re not. Likewise, there are two mid-bosses that are hard to get through without taking some cheap damage. Nonetheless, it remains quite playable overall.

Outside of its original Japanese arcade release, the game’s history is quite obscure. There exists an overseas version labeled as Lightning Swords, for which the ROM and operator’s manual have been archived. It seems that it was released in the UK, where at least two quick reviews appeared in magazines at the time, but there is no evidence of any North American release. The writer – it seems to be the same for both reviews – didn’t realize you were supposed to charge your attacks, and quickly dismissed the game as boring. The game’s text was already in English in the original, so the only difference is the title screen.

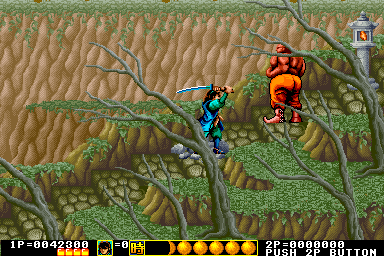

These big guys kind of look like Data East’s Karnov, and even spit fire.

Most of the arcade games Irem released in the ’90s never got a home port, and this is no exception; it also never appeared on a compilation or saw any kind of modern re-release. The only way to play it at home, as of this writing, is through emulation. And it deserves to be played; it’s a fun, short, no-nonsense game that aims to do its own thing and does pretty well at it.

In 1994, the original Irem Corp left the video game business. A new company called Irem Software Engineering was formed around ’97, regrouping former employees from both the old Irem and Nanao. Hiroya Kita (better known as Hirogon), the main game designer behind the known Nanao titles, would go on to direct the PSX-exclusive R-Type Delta there, before moving on to a producer position.

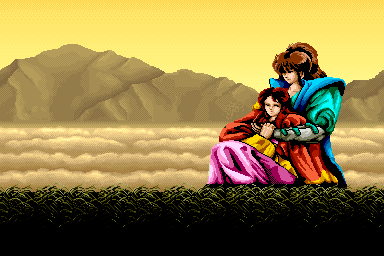

The ending seems to show the same woman who was presumably killed in the opening. Is this only a memory?

Links/References:

The Arcade Flyer Archive has the original flyers, including one with instructions on how to play the game.

Information about Irem and Nanao from this shmuplations interview about Battle Bird, this archived 1up.com interview with former Irem and Capcom game designer Takashi Nishiyama, the GDRI page on Tamtex, various game credits on mobygames.com, and the English and Japanese Wikipedia pages for both Irem and Nanao (now Eizo).