Content Warning: This article discusses poverty, suicide, depression, rape, and other heavy subjects. Discretion is advised.

How do you follow up something like Actual Sunlight? That game was so uncomfortably human partly because it was based on the life of the game’s creator, Will O’Neill, and his real near suicide attempt. His second release, Little Red Lie, is a work of complete fiction and shouldn’t have the same power, and yet it does. It fact, it may be even more powerful. Actual Sunlight was a very personal story, but Little Red Lie is a universal one that hits at quite possibly the most sore of all subject matters – poverty and the wealth gap.

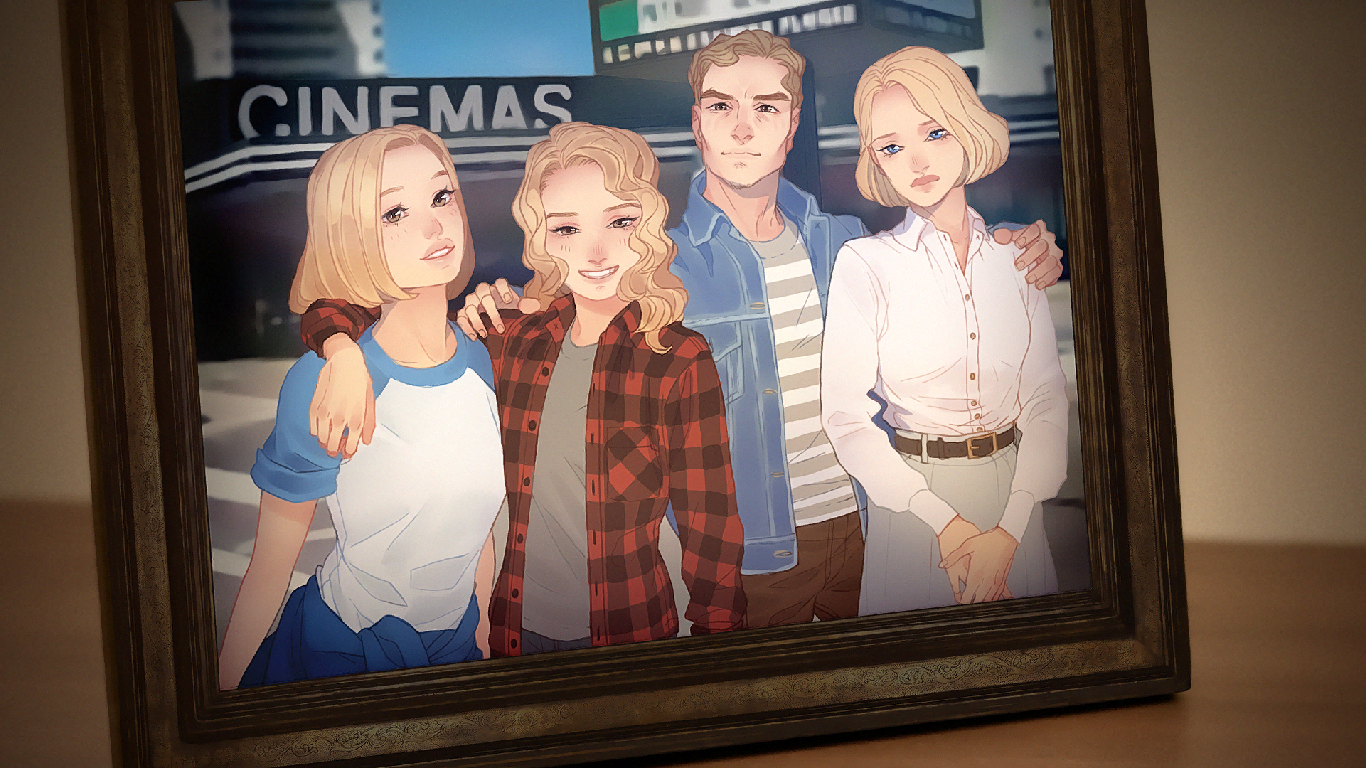

The game follows two different stories, one of failed adult Sarah Stone and one of rich financial speaker Arthur Fox. Sarah is living with her family after her life dissolved around her and she was devoured by debt, trying to rebuild and at least support her parents with a job she’s just recently lost. All the while, she has to put up with her sister, whom has depression and once attempted suicide, yet has become a financial load on the struggling family and stays in her room at almost all hours, draining funds with unnecessary purchases. Fox, on the other hand, is incredibly successful, but his hedonistic lifestyle may finally be catching up to him, and when it comes crashing down, it comes down hard.

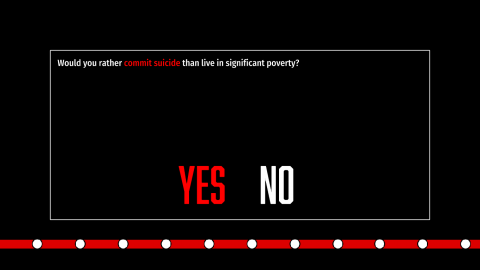

Like Actual Sunlight, there is very little in the way of what one would describe “play,” but the story is enhanced by being interactive. If Actual Sunlight is about the possibilities of life, then Little Red Lie is about the inevitability of reality. To this end, the game gives you the illusion of choice, with moments where you can select some options that almost look like choices until you read carefully and realize you’re just reading the character’s inner thoughts. It’s a subtle way to push the themes of the game, to remind you of how powerless you ultimately are in a situation like this. Sarah’s life is controlled by forces that don’t even know she exists, and Fox’s life is controlled entirely by his selfish nature and inability to emphasize with other people. One can’t move no matter how they choose, and one is unable to make any choice besides the worst one. Both of their situations are born from the same source: Money.

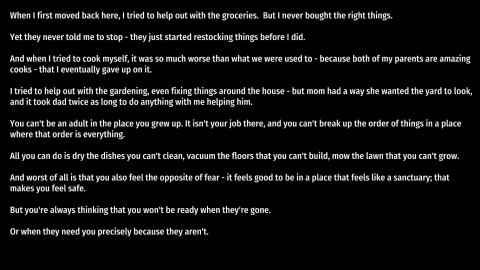

It’s all about the money. Taking place in an economically weak Canada (aka the actual, real modern day Canada), Little Red Lie is interested in examining just how much money impacts all our lives and the lives of others by showing two different scenarios. Sarah’s has no money, where doing the right thing has left her family with nothing. Her father worked the beat all his life and the collapsing invisible giant called the economy drained his savings. One of his daughters is paralyzed with fear of leaving the only comfort she knows, and his wife needs more and more medications and treatments every year. No matter what the family does, they can never get enough money in order to truly survive. We see how Sarah and the Stones live and how they try to hide their shame and desperation, despite most everyone around them suffering the same fates at some point or acting as vultures and prey on what little they have.

The impressive thing about all of this is that O’Neill remembers to keep the cast grounded and sympathetic in some ways, while also making many of them equally despicable. Sarah’s sister Melissa is a great example of this, as she remains nothing but a weight slowly crushing all of her family, but you get an idea of how she ended up like that and see glimpses that a caring human being is still buried under her messy, numb persona. She’s tragic, but there are limits to how much one can sympathize with her because we see how her choices and actions hurt everyone else. The ultimate antagonist of Sarah’s story also isn’t exactly an antagonist either. In fact, they’re even more tragic and sympathetic than the entire Stone family, a reminder that many, many others are suffering the same or in worse ways than you.

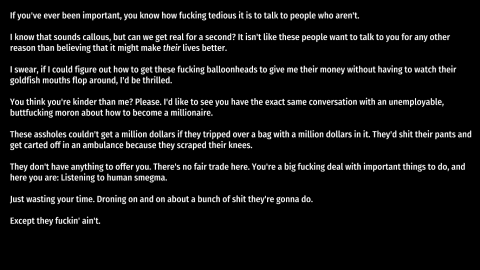

Fox’s story is the fun-house mirror version of the Stones’ story, a man who has ungodly amounts of funds and never has to stress about his position in the world, with exception to his idiotic, poorly defined beliefs in being a “strong” man. As a result, nothing ties him to his family and he indulges in whatever he wishes. The irony is that Fox is just as miserable as the Stones, but he has so much money that he can by quick highs whenever he wishes. He never needs to learn or grow, so he acts as selfishly as Sarah’s depressed sister, and he destroys lives in the process. The interesting thing is that he comes off as a possibly sympathetic figure for half of his story, a complex person with his reasons for the way he is.

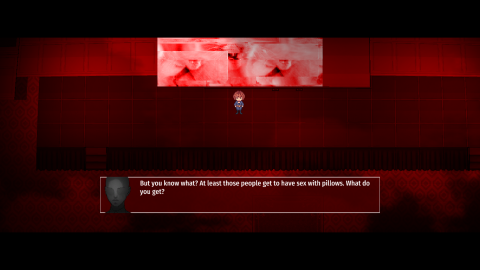

That makes it the more shocking when Will O’Neill inserts himself in the narrative simply to inform the player that Fox, despite his reasons, is a genuinely horrid human being, and that in writing him, he he decided to go against the myth of popular fiction that the rich are somehow inherently better or more interesting than us, deciding not to make fiction that we can live vicariously through. We can humanize and even see ourselves as our abusers, in other words, and he decided not to allow that for the remaining half. From there on, Fox becomes increasingly monstrous, becoming the worst aspects of toxic masculinity in every way imaginable, including a disturbing sequence where he forces himself onto someone else. The brilliance of Fox’s story is that it ends in the exact opposite way as Sarah’s and the two never really intersect, outside one or two minor parts that don’t seem to affect one another at all. It’s not satisfying or cathartic – which is entirely the point. It’s the sort of story that makes you angry because of how vile and true it really is.

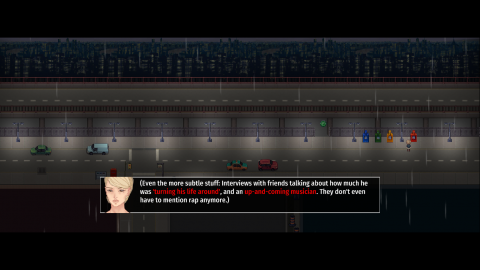

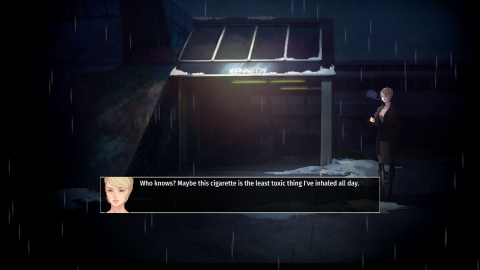

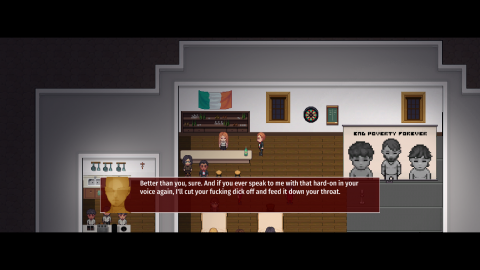

Little Red Lie benefits from a move from RPG Maker to Unity. It still uses the same sort of graphical style, but there are a mess of new affects added that completely transform the game. The game swerves into stories with short, first person narrations highlighted with huge text carefully placed on the screen to highlight points of interest, and instructions are told with massive text that covers the screen and inject a bit of dark humor to the proceedings (“BLAME INTERNET”). Fox’s story also benefits massively from distortion and strange effects used when he’s intoxicated or after particularly grim sequences. The sound design tosses in quite a few curve ball moments as well, while we get a fitting, subdued soundtrack alongside. These touches all greatly enhance the mood of the writing and even fit with the theme of lies, easily the most important element of the game.

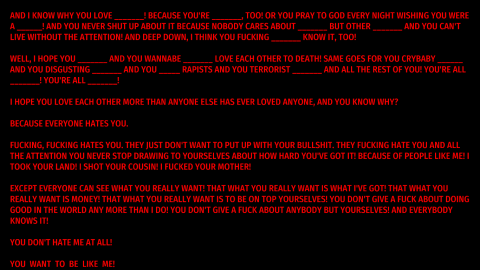

Sometimes words are highlighted red. Outside big instruction text, this always highlights a lie. Characters don’t just lie to each other, but to themselves, particularly in moments of stress or instability. It’s a clever way to give every well written and nearly poetic dialog sequence far more weight by showing us little bits that suggest at some greater truth the characters are ignoring. Perhaps the strongest moment is the entire game is an unhinged, idiotic monologue Fox gives himself, at the end of his rope and unable to accept fault for his actions. Every word is drenched in that violent red, eventually reaching the point where he just starts repeating nonsense that doesn’t have any basis in any reality. The worst events of the game come from a piling of these lies to both others and ourselves. The avoidance of the ugliness in us all can only lead to worse outcomes if not addressed and dealt with in some way. It must be confronted, or it devours us and those around us.

What makes Little Red Lie so memorable, though, is not how uncomfortably real it is, but just how real it is, period. We see highs and lows, hope and sorrow, and even moments where even the worst human beings show signs of being better than they are. I all makes for fantastic tragedy by the end, but also reminds the audience that life is more than suffering, struggling, and fear. The characters, and probably many of you, are living in a mundane sort of dystopia, as Sarah describes in her opening monologue, but life continues on and joy can still be found. Hope still exists, and even if the odds are so small, those small moments can’t be taken from us. Like Actual Sunlight, Little Red Lie is both ugly and beautiful, a game so imperfectly human. The more impressive part this time is that O’Neill isn’t basing this off just his own experiences. This is the product of both empathy and disgust, something real and truly unforgettable.