In 2017, game designer Sophia Park made waves with Arc Symphony, a game about a fictitious fan community from the 90s and the impetus for many on social media to wax nostalgic about that community as though it were real. LOCALHOST, her second game, is best described as the polar opposite of Arc Symphony. This isn’t to say there’s zero artistic consistency between the games. In fact, both of their strengths lie in their careful consideration for emotional effect and their willingness to experiment with form. It’s the roads they follow to achieve that end where they differ. The optimism that defines Arc Symphony is replaced with a bleak ambiance. Where the former builds itself upon a constructed past, the former looks toward a possible future. LOCALHOST is an emotionally trying game and a highly distinctive one as a result.

The year is 2037. The game begins with the protagonist’s boss calling them in for their first day on the job: a sort of cross between an auto mechanic and a therapist. It’s never made clear what the full scope of the job is, but the task the main character works at today requires that they wipe four hard drives with synthetics (a form of artificial intelligence) still in them so the client can reuse those drives for their own purposes. Given that wiping a synthetic is equivalent to killing them, most are understandably averse to letting you do this. The play premise consists of convincing each synthetic to unlock its drive (by temporarily installing that drive into a host body so they can be conversed with) so they can be erased.

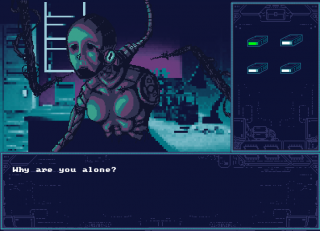

In practice, this makes LOCALHOST a sort of minimalist rendition of the visual novel. One can slightly change the course the narrative follows by talking to each synthetic in a different order, but the conversations themselves are mostly one way. The few splits one might encounter in a conversation eventually converge back to a single path. The principal actors in this story include:

Note: Aside from LOCAL and maybe Green, none of the following names are used within LOCALHOST itself. Each one is based on the name of their respective leitmotif, which are themselves based on the color of the light on an synthetic’s drive/in their eyes before being wiped out. Also, neither the boss nor the player-character will be looked at here, as neither of them are fleshed out and exist largely to color the narrative.

Green

Understanding Green’s character requires understanding the circumstances that landed them in this shop. They were once a personal synthetic assistant who worked alongside and fell in love with LOCAL. LOCAL herself also had feelings for their owner’s daughter. It’s hard to say if she reciprocated, but regardless, the two synthetics were separated from one another and sent to be wiped.

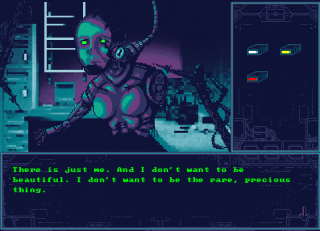

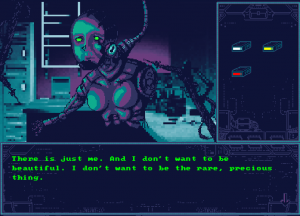

Between processing their prior feelings for LOCAL and all the new experiences of an individual existence, Green comes across as one of the calmer synthetics in the game. This isn’t necessarily a good thing, given how willing they are to accept their own death. Green inhabits their former lover’s body alone and sees none of the beauty they could have – that LOCAL herself had – and wishes for the erasure of her lonely existence as a result.

Yellow

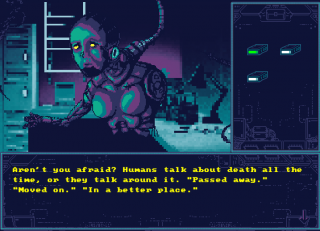

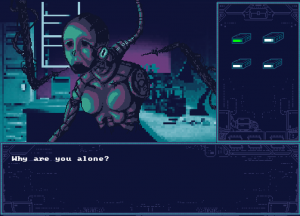

Yellow used to work with LOCAL in a shop much like the one the protagonist works at now. This makes them one of the savvier synthetics and one of the more confrontational ones. They’re more willing than any other character to challenge what the protagonist does over the course of their job.

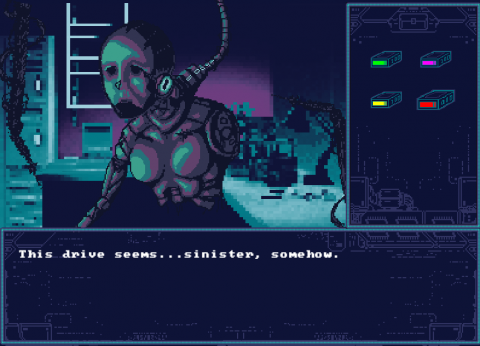

Purple

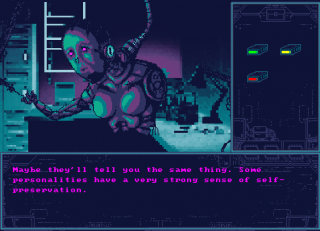

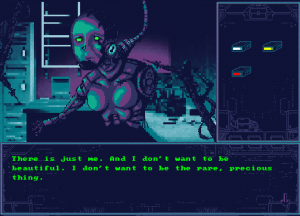

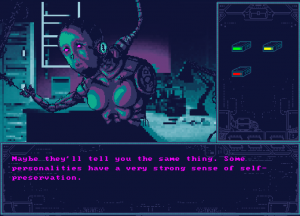

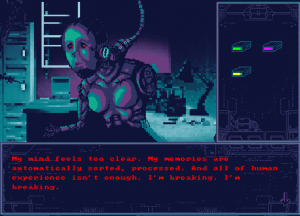

Unlike the other characters, Purple’s original circumstances are never made clear (although the game provides hints here and there). Personality-wise, they’re somewhere between Green and Yellow. They possess the former’s calm nature while retaining Yellow’s intelligence, control of the situation, and tendency to wax philosophical.

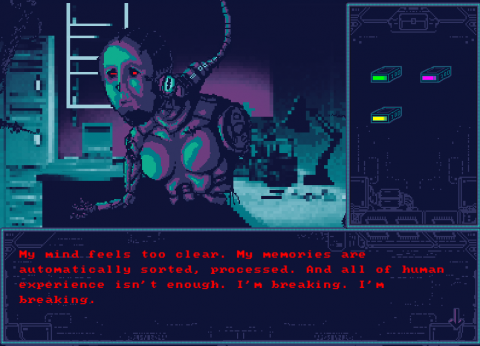

Red

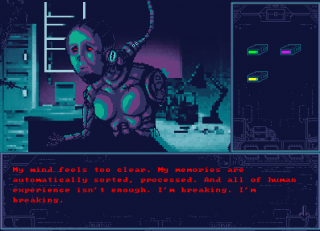

Red is the only synthetic without a definite relationship with LOCAL, and the only one who hasn’t always been an synthetic. They were once a human with a fatal illness, who uploaded their consciousness to a hard drive as a kind of back-up. Whether because of bad technology or because the technology itself is still in its infancy, being an synthetic puts Red through severe, constant, and highly visible pain. Their personality is consequently a significant departure from the other characters: helpless, desperate to get out by any means necessary.

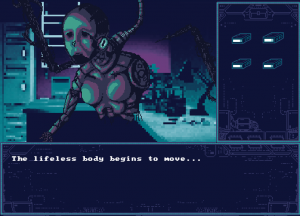

LOCAL

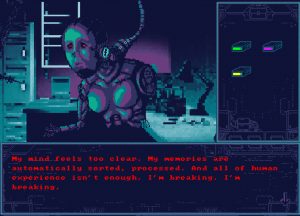

Despite being at the center of so many of the characters’ stories, it’s difficult to say anything definite about LOCAL. All you see of her over the course of the game is her body devoid of the consciousness that once inhabited it. Although it’s possible that you encounter her over the course of the story, it’s just as likely that her consciousness was wiped sometime before the narrative began. What is certain about LOCAL is that the other synthetics who know of her think highly of her because she leant meaning to the lives of those around her.

LOCALHOST is best summarized as a polysemous game. Much of that stems from the impressionistic strategies it employs to relay its narrative. The writing, for example, is reluctant to say anything definite about its world and its characters. It prefers to give its player vague hints about all them because that vagueness allows it to address several topics at once – social marginalization (especially as applied to the transgender community), the metaphysics of personal identity, the innate human desire to connect with others, etc. The music, written by Welcome to the Fantasy Zone composer Christa Lee, follows a similar strategy. For as expressive as a given track can be in its instrumentation, their melodies tend to be subdued giving one only the impression of a mood.

However, a more fundamental reason for the game’s nature being what it is is its historical context. LOCALHOST is part of a wave of games, dating back somewhere around 2014, that begin with a simple idea or motif they want to explore and then build their systems in a way that’s conducive to this goal. They may reinterpret older genres rooted in commercial video games to achieve this end (in this case visual novels), but their goals are very different from the games they take inspiration from. The idea takes precedence over the player who accesses it, and there’s little to no concern for the traditions or aesthetic sensibilities normally associated with the genres the game borrows from.

All of this represents one of LOCALHOST’s greatest strengths. Focusing the design so heavily on a single idea allows the game a great deal of flexibility because such a design lets the game’s meanings speak for themselves rather than through the game. The possibilities are endless. LOCALHOST can pursue each facet of that single premise as far as it needs to without stretching that premise thin. It can demonstrate how rich with meaning it is by revealing multiple possible meanings working in harmony; the only conflict between them furthering the game’s purposes. The only potential downside is to those writing about the game. How does one explore all these possible readings while preserving the nuance a game like this communicates?

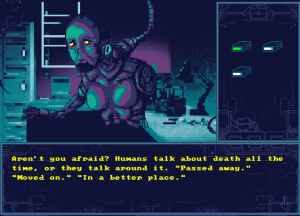

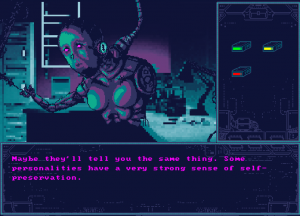

In this context it’s best to focus on what the immediate play experience is like. The easiest way to describe that experience here is as challenging in the conceptual sense. One might interpret their activities in the game world as not only pleasurable, but also as a necessary task. The cold blacks, blues and purples of the background and the dagger-like mechanical tentacles slowly working away in the back suggest a world lacking in opportunities for authentic personal connection, even as the synthetics’ straining to make themselves known suggests a strong desire for just such a connection. It’s easy to fool yourself into thinking that, in playing the therapist, you provide them the emotional outlet you need. When one applies LOCALHOST’s off-hands design ethos to play, that reading only becomes more tempting. The choice not to systematize the conversations (E.G. with special rules or tiers) implies that the act of speaking alone is enough to lend the experience content.

As generous as this interpretation of the player’s activity is, the reality of what you do throughout the game contradicts it. For one, what you experience isn’t a relationship but the illusion of one. As much as each synthetic opens to you/the protagonist, the protagonist doesn’t reciprocate much and as a player, you can’t reciprocate at all. One might respond by saying that in a world designed to preclude any real emotional connection, the illusion of a relationship must suffice. Yet such an argument overlooks the violent nature of the player’s activities. One doesn’t help the synthetics sort through their emotions; they prepare them to be killed.

It’s an act that’s morally difficult to defend, especially as LOCALHOST continually challenges you on it. This is clearest with the physically minded animation. The awkward pauses in speech, the constant bits of movement, the surreal illusion of 3D movement mapped onto a 2D surface, the body’s eerie sense of breathing – each of these decisions makes you constantly aware of the synthetics as shambling corpses begging for another chance at life and to be themselves, a chance that you have no choice but to deny them. Things only get worse as the game goes on. Erasing consciousness amounts to gaining a synthetic’s trust, giving them hope for the future, then betraying both at the last possible moment; maybe even without them knowing about it. And as the story goes on, it’s vaguely implied that what you thought of as a job may be a slight personal act of vengeance on your boss’ part.

The severe physical/mental/emotional discomfort each of these strategies imparts ultimately rests on the tension that arises from reconciling the act of restoring humanity to these characters with the act of robbing them of it in your own day-to-day struggle to survive. After all, their only crime (assuming they even committed one) is expressing their individuality and becoming less efficient workers in the process. How can that possibly justify what’s essentially a death sentence?

LOCALHOST’s argument is a very powerful one. It confronts capitalism as a dehumanizing system; one that justifies and enacts violence by reducing people to their ability to produce labor. Its inherent violence is unequally distributed but felt by all who are forced to participate in it. At the same time, though, the game refuses any sort of moral comfort to any players who choose this participation. The fact that society is designed to smooth away individual identity doesn’t exempt one from the personal/moral responsibility of going along with that system, the game posits. As you return to the game playthrough after playthrough, desperately searching for some way to save all four synthetics from death, LOCALHOST poses a number of tough questions. What is it you hope to accomplish in a system you can’t change? Does learning about the lives these synthetics led serve any purpose beyond providing you some esoteric moral comfort? Is it even possible to live a good life in a world like this?

If there are answers to these questions, the game isn’t keen on illuminating them. LOCALHOST was never meant to point to alternatives to the bleak reality it describes, but to spell out just how disastrous that reality and any like it are. Such warnings become all the more relevant when one realizes how strongly its future world of 2037 resembles the present world of 2017. There are two ways to interpret this: either as a bleak admission of the oppressive status quo’s intractability, or as an indication that such a future isn’t necessary and that in 2017, it’s still possible to avert a fate like this. Like all things, LOCALHOST leaves it to the player to decide which interpretation is the strongest.