- Lords of Midnight, The

- Doomdark’s Revenge

- Lords of Midnight: The Citadel

- Midnight/MU

- Legions of Ashworld

The name Mike Singleton might not be instantly recognizable to most gamers. While he did work on several highly successful projects, most recently Race Driver: GRID, he usually wasn’t the main designer responsible for the overall style of those games. Singleton’s most important creations are much older and made for a smaller audience – they were not the big budget console hits but creative, visionary computer games made in the 1980s at the height of the popularity of British microcomputers. The most important of Singleton’s games were Midwinter series of first person action-RPGs and Lords of Midnight, a unique blend of strategy, adventure and role-playing.

Lords of Midnight series consists of three games: The Lords of Midnight, Doomdark’s Revenge and Lords of Midnight: The Citadel. The first two titles have the players controlling characters from a first person perspective and in a turn-based fashion as they travel across the game world gathering armies, looking for allies and trying to confront an overwhelmingly powerful enemies. They also combine elements of strategy and adventure, trying to accommodate different possible playstyles. The Citadel kept the focus on alliances but experimented with real-time strategy, largely to its detriment. Another game, The Eye of the Moon, was planned but never developed. In addition to the official titles, fans of the game created a semi-unofficial (made by fans but hosted on Chris Wild’s Icemark severs) multiplayer variation known as Midnight/MU which in turn inspired Legions of Ashworld a first-person strategy game with a Middle-Eastern theme created by Jure Rogelj, the artist behind mobile remakse of the first two Lords of Midnight games.

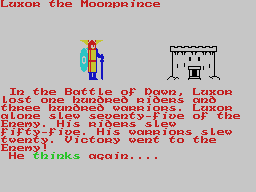

All the Lords of Midnight games are set in a high fantasy universe which bears more than a passing resemblance to Tolkien’s Middle-Earth. The central characters here are Luxor the Moonprince, rightful ruler of the Free (basically humans) and owner of a magical ring which allows him to see through the eyes of his allies and give them commands regardless of distance between them, his son Morkin, a ‘chosen one’ type of character destined to do great things despite not being the most competent warrior out there and Rorthron the Wise, a powerful wizard. In their journeys, they meet Fey (basically elves), skulkrin (orcs/goblins), trolls and dragons. They fight against evil rulers powered by dark magic and try to keep their lands safe, free and prosperous. While this is as standard as fantasy stories get, the world design and gameplay style turn Lords of Midnight into something much more than the fairly generic setting would suggest.

Night has fallen and the foul are abroad.

The backstory of Lords of Midnight is told through a short story placed in the game’s manual and by its end, Luxor, Morkin, Rorthron and a Fey warrior Corleth set out from Tower of the Moon to fight a war against Doomdark The Witchking of Midnight, an evil mage who killed the previous king and usurped the throne. As the game begins at the winter solstice and Doomdark’s power come from the Ice Crown, the villain is at his most powerful and orders his armies to attack strongholds of the Free. From this point, the player takes control of the characters and attempts to fulfill one of the two victory conditions: destroying the Ice Crown (which can be only done by Morkin as he’s immune to its power and thus able to safely touch it) or storming the fortress of Ushgarak and killing Doomdark. The game is lost if Morkin is killed and either Luxor dies or Doomdark takes Xajorkith, the southernmost fortress.

While the game’s story never strays too far from its main influence, the genius of the game’s design lies in how its mechanics connect to the plot without resorting to linear, scripted sequences. As Doomdark is able to sense Luxor’s Ring of the Moon, it is beneficial for him to be surrounded by large numbers of warriors, riders and allies. As the Ice Crown uses Ice Fear to defend itself from those wishing to destroy it, sending Morkin north to look for it is helpful as it means that Luxor’s soldiers won’t have to deal with too much Ice Fear – but as Morkin isn’t too good at recruiting and is pretty useless in combat, it’s best for him to avoid any confrontation with the enemy. The game naturally lends itself to the playstyle reminiscent of how events played out in Lord of the Rings: Luxor-Aragorn leading a military campaign against the forces of evil while Morkin-Frodo travels with a small group of companions, attempting to infiltrate the enemy’s lands and destroy the artifact that gives them power. In fact, The Lords of Midnight is a better Lord of the Rings than any officially licensed LoTR game. Of course, the player is still free to play the way he wants – if you know exactly what to do and don’t get surrounded by enemies, you can speedrun the game while completely disregarding the strategy elements.

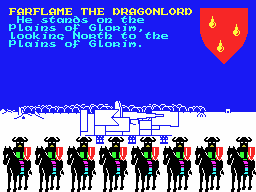

Unlike almost every strategy game ever made, The Lords of Midnight is played from a first person perspective. This, combined with grid-based movement, makes it slightly similar to dungeon crawlers like Wizardry – as none of the 8-bit versions contain an automap, this means that players will need to bring out the graphing paper and do a lot of cartography. Things to look out for include: terrain features (they all have an effect on movement speed, forests also give Fey forces an advantage in combat), locations of items, strongholds (allow recruiting soldiers and give an advantage to soldiers stationed there), towers (Wise living there give tips ranging from useless like ‘Lord of XYZ might be found in the land XYZ’ to essential advice on destroying the Ice Crown) and recruitable lords. Like many other game mechanics, the lack of in-game map combined with the panoramic first-person view and the need for spatial orientation serves a storytelling purpose: it makes the world seem bigger and the approaching enemy armies (with banners visible in the distance at first and then, as they draw closer, replaced with armed men standing in a line) more threatening than if they were seen from a zoomed-out top-down view. The player’s limited line of sight also plays part in this as if the enemy’s not immediately visible, it’s impossible to know where he is and how many soldiers he has left.

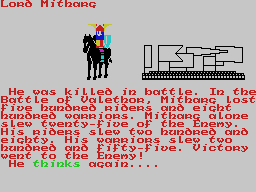

The Lords of Midnight is a turn-based game: the player moves during the day while the enemy travels at night, with potential battles resolved after both make their moves. Characters controlled by the player (four initial party members and everyone they manage to recruit) have a limit of how far they can go represented as a passage of time: each starts at dawn and uses up remaining time when moving (how much time is used is determined by terrain type and whether the player is on foot or on horseback). This may sometimes lead to amusing situations: if you recruit a character just before the night, he is available from the dawn of the same day, as if time flowed differently for everyone. Travelling makes lords and soldiers tired (both warriors and riders travel at the lord’s speed, although warriors get more tired) while the level of Ice Fear in the visited areas affects their morale (those effects can be counteracted by resting in towns and finding special items). Exhaustion, morale, army size and lords’ individual fighting skill (even the weakest ones can kill dozens of common soldiers) determine the outcome of the battles while encounters with wild animals and monsters annoyingly only take lords’ statistics into account, making it possible to lose a huge army because a leader was eaten by wolves. This is especially annoying if said leader is Luxor as if he dies, the player loses control of everyone other than Morkin (unless he travels to the place where his father died and retrieves the ring).

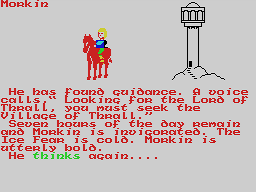

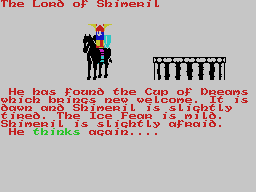

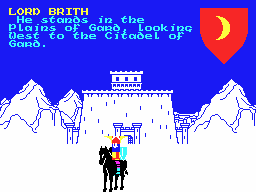

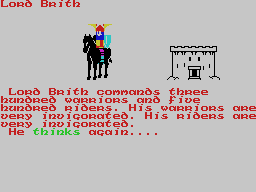

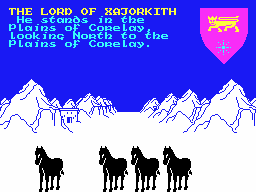

Graphics in The Lords of Midnight consist mostly of static images: character sprites, coats of arms and panoramic first-person views. The former two are simple yet stylized to look similar to medieval paintings – the end result is pretty great (especially given Spectrum’s limited graphical capabilities), although unfortunately Morkin is the only character to get a unique sprite (all the others use generic sprite for their race). The latter is created by a process Singleton referred to as landscaping: contents of each tile in the character’s line of sight are drawn, placed in a specific position on the screen and scaled appropriately, unless the view is blocked by larger sprites (e.g. mountains or forests). The method is not unlike a primitive form of raycasting, the process used in later games like Wolfenstein 3D, although none of the math is done in-game: the game’s strictly grid-based nature allowed Singleton to create lookup tables with all appropriate values so that the game doesn’t need to do resource-consuming calculations (even this way, it still isn’t instant – especially on Amstrad CPC).

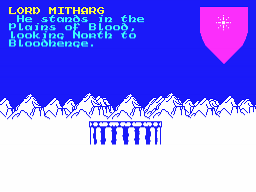

While the game has no music or sound effects, it does attempt to create atmosphere with in-game text. Instead of putting dry information about the player’s location, the descriptions are structured like sentences from a novel: ‘He stands in , looking to ‘. Statistics like exhaustion and morale are also described instead of showing players a number: characters can be ‘bold and invigorated’, ‘afraid and tired’ etc. While this does help immerse the players in the game’s world, the overall effect is slightly hampered by the fact that writing in the accompanying short story isn’t that great and by the fact that the characters have completely ridiculous names like ‘Lord Blood’, ‘Lord of Xajorkith’, ‘Lord of Dreams’ (those are based on the names of places they rule – Plains of Blood, Citadel of Xajorkith and Forest of Dreams) or ‘Doomdark the Witchking of Midnight’.

The game’s interface takes some time getting used to as it was designed with a keyboard overlay in mind. While most of the keyboard commands aren’t too difficult to learn for anyone used to playing old computer games, choosing direction with number keys can be frustrating as the directions don’t correspond to those on the numpad (something ZX Spectrum keyboard simply didn’t have), instead having one 1 represent north and every number after that (up to and including 8) being the direction you get when you rotate 45 degrees clockwise from the previous one. Also, the character select screen doesn’t indicate which characters can move and which don’t have remaining daytime, are too exhausted or have already been killed.

The Lords of Midnight was originally released on ZX Spectrum and then ported to other 8-bit microcomputers: Amstrad CPC and Commodore 64. Those versions play exactly the same (save for differences in performance due to hardware differences) but look different due to different color palettes used by those systems. C64 version is probably the best of the bunch as its colors are fairly easy on the eyes and performance isn’t bad either. In the early 1990s, a fan named Chris Wild reverse-engineered the original Spectrum game and ported it to IBM-comaptibles by directly translating most of machine code instructions and writing a graphics engine that made the PC game look like the original. In later updates, he improved the interface by allowing the optional nunpad-based navigation and giving indicators if the characters are able to move on the select screen, thus solving the biggest problem with the original game. It also works really fast on modern computers so you won’t have to wait too much for the game to move AI-controlled characters and resolve battles during the night. This put him in contact with Singleton and, from this point onwards, made him into an important figure in the future development of the series. This PC release is available as freeware and readily downloadable from Chris Wild’s website. It’s also included on Lords of Midnight: The Citadel CD, along with Doomdark’s Revenge port.

In the 1999, Chris Wild created yet another PC port: The Midnight Engine, a highly modular game with the original The Lords of Midnight included as a scenario. This version featured a mouse-based interface (although with an ability to use the original keyboard controls) and technically improved (but not as memorable) graphics by Jure Rogelj while retaining the original gameplay. In the early 2010s, Singleton, Wild and Rogelj teamed up once again to release The Lords of Midnight on mobile devices (unfortunately, Singleton didn’t live to see the release of the finished product as the iOS version was published about two weeks after his death). This version has the graphics stylistically similar to the original but remade using vector graphics and the interface appropriate for touchscreen with movement done by swiping. It also features a welcome change in allowing the player to group the characters so that they automatically travel and fight together, reducing the need to micromanage all the movements and a slightly controversial one in introducing an automap which greatly reduces the difficulty. It was ported to OS X the same year and to Windows in 2013 but it doesn’t support some display resolutions, forcing the game into a windowed mode while also not retaining some of the keyboard shortcuts. Ultimately, it’s not an essential buy as the freeware versions are still playable (original port through DOSBox and The Midnight Engine natively) while the game can still be enjoyed with old graphics and no character grouping.

The Lords of Midnight is a great game that is still enjoyable even today. It’s also one of the best examples of the creativity and talent that can be found in old, forgotten home computer games of the 1980s. The idea behind the game is unique even to this day and the programming skills that made it possible to create such a program on the old 8-bit computers is impressive but what really makes the game stand out is how it blends different video game genres to create gameplay that naturally goes together with the story. It’s also an example of the storytelling potential of video games as it uses interactivity and graphics to make an obviously derivative setting and plot memorable and emotionally engaging.

Screenshot Comparisons

Links:

Icemark – website maintained by Christopher Wild, the developer of PC and mobile remakes of Lords of Midnightgames

Official website of Lords of Midnight and Doomdark’s Revenge remakes

Official Midnight/MU server

Legions of Ashworld official website

The Lords of Midnight and Doomdark’s Revenge at World of Spectrum

Mike Singleton at Planet Sinclair

The Eye of the Moon at Games That Weren’t 64

The Eye of the Moon design notes by Mike Singleton and Chris Wild

Dream a little bigger: a legacy of Mike Singleton at Eurogamer

Official website of Lords of Midnight and Doomdark’s Revenge remakes