Video games have provided an escape from reality for decades. But the first and foremost method of escapism is found in the human mind, in dreams. Dreams have always been a popular theme and setting for storytelling, and video games are no exception. Games like Rez, Psychonauts, and the NiGHTS… series are heavily influenced by the concept of dreaming, but only one game truly captures what it actually feels like to experience a dream. Hiroko Nishikawa kept a detailed dream journal for over ten years. Osamu Sato combined those dreams with creative gameplay mechanics to create a rare gem in LSD: Dream Emulator.

LSD was released in Japan and has never been localized outside of it. Physical copies of the game are extremely rare and have fetched high prices. LSD also became available on the Japan PlayStation Network in August 2010, making it legitimately available to an entirely new audience. And while the game’s content might not be accessible to the average gamer, there is hardly any necessary text, and what actually needs to be read for playing is in English, making it extremely playable.

And LSD is exactly what it sets out to be: a playable dream. There has never been another video game that so effectively conferred the feeling of an actual dream. The game shows its age a bit and certainly has its flaws, but it is still an experience well worth exploring.

The game begins with a psychedelic opening video followed by a simple menu screen, with a counter telling you how many days, or dreams, you have experienced. LSD does not save your progress automatically, so you have to purposely save to the memory card. This is easy to forget to do, as playing for an extended time puts you into an odd state of mind.

Your first dream begins in a house, facing a window. This is the default starting position, but your starting location varies widely the more you play. There are many areas to be explored, from areas like a Japanese village to many surreal, Dali-esque locations. While the layout of the game appears to be quite random, it is static and mappable. I recommend, however, avoiding using a map until you’ve had a chance to play without.

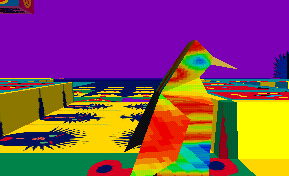

The graphics in LSD are dated but adequate. The look of the 3D environment should be familiar to anyone fortunate enough to survive gaming in the 1990s. Simple blocky shapes are textured to appear as buildings, trees, a flying whale, jumping baby men and everything else that LSD throws at you. Despite their technical simplicity, the visuals are more than sufficient to convey Nishikawa’s bizarre night time fantasies.

Moving in LSD is fairly simple. The directional pad turns you and moves you frontward or backward. There are some additional options, as the L1 and R1 buttons allow you to look behind you, while L2 and R2 are for strafing. X allows you to run, which is helpful in the larger areas.

There are two ways to reach different settings in the game: taking tunnels and bumping into things. Tunnels are static routes from the various large areas in the game. As for bumping: touching anything in the game–whether it be a wall, a flower, or a minotaur pulling a cart–will link you to a new location. Whether by walking or linking, transitions are marked by the screen fading to a solid color. White and blue seem to be positive transitions, while a red transition generally signals that the dream is taking a darker turn.

With the first step you take in LSD, you become aware of what might be the game’s greatest fault – the sound of footsteps. Somewhat unusual for the time, the game designers attempted to truly simulate walking. The view moves up and down as you walk which is fairly normal in first-person games today, and fairly unobtrusive. However, they also attempted to realistically portray footsteps, but fail miserably. There is both the monotonous tap-tap-tap on most surfaces, as well as the fact the sounds just come too quickly to sound anything like a person walking. This is honestly so annoying at first that it puts many people off of trying the game. But like many minor annoyances, you get used to it, and you become so busy watching what happens in the game to be distracted.

The soundtrack makes up for the footsteps. The game is often said to contain over 500 songs, called patterns, which are actually wide variations on the same basic tune using a variety of electronic and environmental sounds. Each time a scene changes in the dream, the music will adapt as well. Sometimes, before a particularly scary moment, the soundtrack cuts out completely, which feels quite dramatic. Yet despite the constant changes, the music still has a unified feel.

This same unity is felt throughout the entire experience. Perhaps because the game is based on the dreams of a single individual, the world feels like a consistent whole. The game feels authentically dreamlike in a way most media is unable to achieve. The variety of events, characters and locations truly feel like they sprouted from the same mind. There is a logic, however dreamlike, that ties everything together.

Each dream lasts up to ten minutes, during which you can walk around and bump into things to your hearts content. However, triggering a video will end the level, and seeing certain things will kick you out of the dream. Also, dying always ends the dream. I have managed to perish by falling off of cliffs, getting shot by a creepy guy in black, and getting squished by a ceiling. Although you can die in LSD, there is no combat. Other than the aforementioned creepy guy, any other character’s attack, whether it be wolf, demon, or dragon, simply links you to a new location. You can try to dodge the grey man, which is difficult, but most of the time you only interact with a character by following it or bumping into it. Just as you can rarely see your hands in an actual dream, you are unable to manipulate anything in LSDs dream world.

The world of LSD is populated by an assortment of characters. A bunny and bear sometimes appear frolicking in Happy Town, and a woman’s head fell off as I approached her in the Violent District. The most interesting character is probably the grey man, who can appear anywhere in the game world without warning. He appears out of nowhere and walks toward you slowly. When he reaches you, the screen flashes and he disappears.

LSD is unusual in that goals inside the game are set by the player. There are no missions, no princess to rescue. The entire point of the game is to explore the dream world and see all there is to see. One might spend several dreams trying to witness a random character or event (of which there are many), or try to find a path to a specific location.

There is one small exception: the graph. Following each dream, a graph appears on the screen, showing where the dream rated in relation to being an Upper, Downer, Static, or Dynamic dream. A blinking red dot marks the dream that is just completed, while past dreams can be seen as other colors.

The disc image supposedly contains a video file, ENDING.STR, which no one can open. A video on Youtube claims to be of this video, and states that it plays when the entire graph is filled. This is unsubstantiated, and attempting to fill the graph is honestly quite frustrating. It is difficult to know how your actions in a dream will be represented on the graph. I attempted to control the graph–by frantically changing scenes or by standing completely still–but it did not seem to affect the Dynamic/Static rating at all.

As a player racks up days in LSD, the game adds variety to keep things fresh. This is done primarily by swapping textures. For instance, instead of the building having windows and doors, they will be covered with women’s faces or cartoon characters. This gives the game a very interesting and enjoyable look. Unfortunately, I found that the game became less and less playable as I neared the 100 day mark, as many locations became a bizarre assortment of textures. Many surfaces also became transparent, making navigation difficult.

Sometimes, instead of actively playing a dream, selecting start will begin a surreal live-action or computer generated video. There are numerous such videos, which manage to be fairly creepy despite the poor file compression. One such dream involves a goldfish bowl in an elevator, while another is a negative exposure of a crowded subway. There are also dreams which are simply a black screen with white Japanese text. Some of these text dreams have translations available, and add some depth to the progress of the game.

Once you have played 20 days, you gain the option to flashback. This gives you the ability to experience an abbreviated form of the previous dream. But if you die or come into contact with the grey man, the flashback option disappears until after finishing another dream.

Due to the lack of clear goals, this is the type of game that one plays extensively for a short time and then occasionally revisits. There are aspects of the game that I wish were different, but changing the gameplay would remove that authentic, dream-like quality. There are several psychedelic games with things the gamer is meant to accomplish – Psychonauts, for one, and Eastern Mind: The Lost Souls of Tong Nou by LSD‘s Osamu Sato. As for LSD, sure, there isn’t really a final goal in the game, but since when have dreams needed a point?

Honestly, it would be appropriate to compare LSD to Windsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland, Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman, Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams, Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland books, and other works of art designed to emulate dreams. Judging by LSDs popular Let’s Play videos, multiple blog appearances, lengthy forum discussions, and the extensive filesharing of the game ISO itself, there is a demand for hallucinogenic, experiential games. And with the rise in casual gaming, a remake or spiritual successor to LSD could easily prove popular. There is definitely an audience just waiting for such a game to appear.

As the game was quite experimental, the sales weren’t exactly high, and as it disappeared from the market, second hand copies became very expensive. Luckily, it is cheaply available on the Japanese PSN for play on the PlayStation 3 or PSP.

Other Media

LSD was released as a standalone game and in a limited edition. The limited edition included all three parts of the LSD project: the game, an audio CD, and a book. The CD and book are also based on the dreams of Hiroko Nishikawa.

The CD, Lucy in the Sky with Dynamites, includes twenty short tracks of the game’s musical patterns, remixed for the sake of aesthetics. It lasts just over an hour and contains tracks such as Post Hypnotic Neon Vacation and Silver Mutant Children. The music itself could be considered acid techno, which may or not be intended as a pun.

Tuesday, January 12, 1988

A World I Know

Where is this? It looks like the grounds of a shrine, like a deep, dark forest. I’m wandering around. I can’t get over the feeling that I’ve been to this place before. The temple and the tower look much bigger than usual, and I feel as if I were lost in a world of immensity. It’s very dark with no sky up above, like being in the depths of the earth. Anyway, it’s a world I know.

Another CD soundtrack for the game is floating around online. It’s entitled LSD and Remixes and is a two-disc set. The first disc contains longer remixes than those of the other album, and the second disc contains tracks remixed by guest musicians, including Ken Ishii, known for his work on Rez and Lumines II. This album is often mistaken for the bonus CD that came with the game.

The work of MikeNnemonic was extremely helpful in the creation of this article.