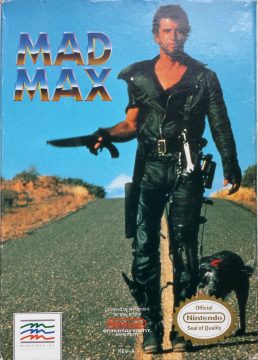

Despite the popularity of post-apocalyptic movies dying down a bit in the late eighties, and countless video games released in imitation of the three Mad Max films, it wasn’t until 1990 that the official Mad Max game would be appear on the NES from Mindscape. In this one year Mindscape attempted to do for the NES what Ocean had done for the Commodore 64: Make a profit off movie fans by churning out as many barely playable adaptations of their favorite movies as possible. In just one year Mindscape delivered video game adaptations of Mad Max, Dirty Harry, Days of Thunder, and The Last Starfighter. Future games based on The Terminator and even Flight of the Intruder would follow in the early nineties. None of these games are particularly good, and some like The Terminator are almost unplayable. Their earlier attempts like Mad Max and Dirty Harry, however have a few interesting ideas that make their flaws stand out even more.

Mad Max starts out promising. Despite the title screen and cover using logos from the original movie, the cover itself and opening of the game makes it clear that this is a game based mostly on Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior. A text crawl of that film’s opening narration is accompanied by Mindscape regular Nick Eastridge’s take on Brian May’s (no relation to the Brian May of Queen) Mad Max 2 score. It’s pretty good rendition, which is fortunate because it’s THE ONLY SONG IN THE GAME. There’s a 1.5 second panicked jingle that loops for way too long whenever you lose a life, receive a password, or enter an Arena level. Whenever you enter a shop or reach the game’s final boss, you just get to hear that theme song again.

This may explain why Eastridge is not actually credited in the manual itself, but the credits of Mad Max in general are a bit more convoluted than that. Both Mad Max, Dirty Harry, and a few other Mindscape games were developed by Chris Gray’s short lived Gray Matter Enterprises (Space Funky B.O.B., Incredible Crash Test Dummies). Some confusion comes up here, as Chris Gray made a name for himself designing Infiltrator> for Mindscape, and its success is what inspired him to create Gray Matter Enterprises in 1986.

Many sources confuse this developer with the unrelated Gray Matter Interactive (Return to Castle Wolfenstein, Call of Duty: United Offensive) that was formed two years before Gray Matter Enterprises would become defunct in 1996, thinking they are one company. To make matters worse, despite many of their games (such as Mad Max and Dirty Harry on the NES) clearly stating on the packaging that they were developed by Gray Matter, they are often not credited properly for their work on many of their late 80s and early 90s games. Mad Max‘s manual isn’t particularly helpful either, providing a lengthy “Special Thanks To” list of various marketing, QA and promotional associates rather than the individuals within Gray Matter who actually made the game.

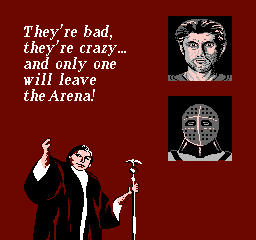

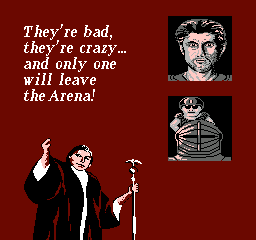

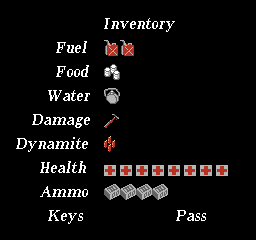

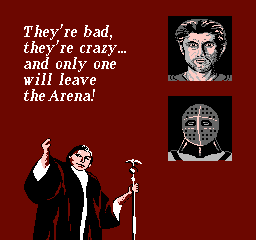

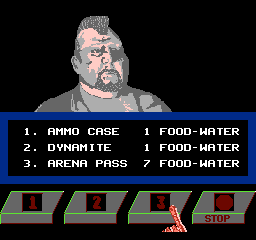

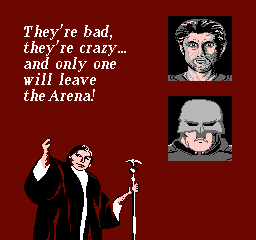

Mad Max‘s structure is ambitious, a more in-depth iteration of what LJN completely failed at with their adaptation of Jaws. The game consists of three levels. The first half of each level involves you driving Max’s iconic V8 Interceptor through various wasteland areas where you break into gang infested warehouses to steal resources and also stop by shops to repair and refuel your vehicle. When you have enough food and water to barter with, you can buy an Arena pass. This lets you progress to the second part of each level. Here Doctor Dealgood from Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome announces that “They’re bad, they’re crazy… and only one will leave the Arena!” We also get to see a portrait of Mad Max based on his look in that film along with his rival in the Arena, the infamous Master Blaster!

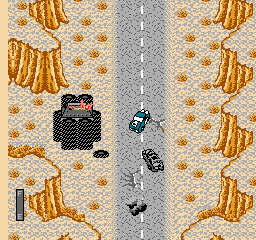

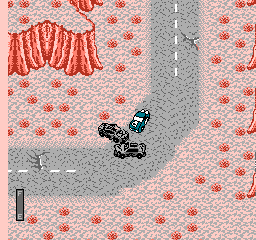

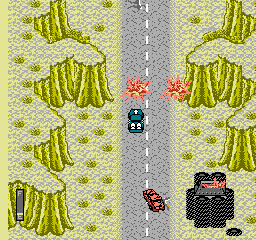

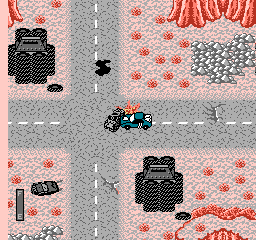

Then the Arena stage begins – they seemingly couldn’t use the Thunderdome concept as well as the name, since the Arena here is actually a demolition derby with many other cars. This is the fun part of the game: it’s chaotic, and many of your opponents will kill themselves off for you by careening off the sides of the track or into each Arena’s many trap doors. They can take some time to complete, however, as you are not allowed to leave until EVERY opposing vehicle is destroyed. The second arena stage uses a portrait of… an unrecognizable guy in a helmet as your nemesis, while the third uses an image of Lord Humungus from Mad Max 2.

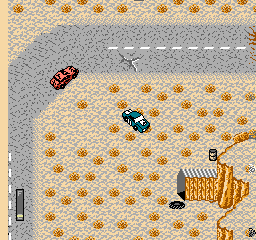

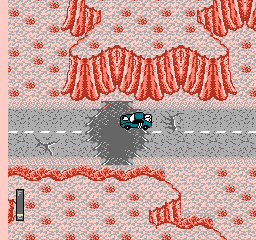

When you complete this final Arena the game shifts to a side view as you engage Humungus in a crossbow duel that makes for an insufferably long battle. Afterwards, we’re treated to a static image of Max’s car with text asking the player “And where does a man like Max go from here?” It’s pretty short, basic in structure, and plenty of liberties are taken with the events in the movies to present the game. There’s only one problem: The entire first half of each level provides some of the most aggravating gaming on the NES. It’s difficult to describe just how poorly thought out the controls are. Turning, braking and accelerating are actually very responsive, but the Interceptor in this game has no speed between parked and rapidly smashing into a wall. This works great in the Arena stages where causing uncontrolled mayhem is the best way to win. In the more methodical wasteland segments where you have to explore and scavenge, however, the endless stream of cars ramming into you and sticks of dynamite being hurled your way and badly implemented controls will slow you down so much that you’ll often find yourself losing a life by running out of fuel rather than from suffering damage.

It seems like a completely backwards decision to put such a tight fuel limit in place that you effectively have to map out these areas like you’re playing Legend of Zelda to track places you can enter and where the Arena entrance is. Doing this while playing means stopping the game every two seconds to take out your trusty graph paper, as you run out of gas and die in five minutes flat if you’re not destroyed by oncoming vehicles. Knowing this, Mindscape kindly provides a map of the first area in the manual, but for the rest of the Arenas and outdoor areas you’re on your own. Mindscape crafted a game based on movies where the primary draw is the fantastic usage of cars and high speed crashes, and then designed it in such a way where you have to constantly come to a full stop and worry about saving up resources to purchase fuel.

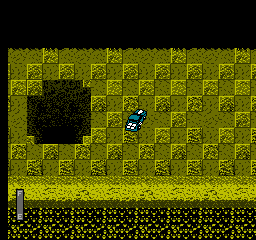

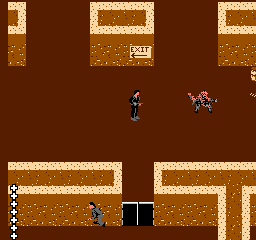

To refuel your car and afford that arena pass, there are entrances to mineshafts scattered throughout each level. When you enter these, the action is viewed from overhead but you get to control Max himself and navigate through some very boring mazes seeking out keys to get access to the rooms with extra food, fuel, and medical supplies. While walking around you’ll encounter annoying marauders that attack you by clinging to you like in Kung Fu or Vigilante, but you have a rapid-firing shotgun to deal with them. While it’s easy enough to stop them (causing them to melt in a bloody heap that is somewhat impressive for an NES game), it makes their presence more of an annoying waste of time that pads out your exploration rather than adding a fun challenge to it.

This is especially frustrating since while the Arena matches you’re saving your resources for are a blast in short bursts, they’re too simple to base an entire game around, and aren’t really worth the time to learn the layout of each wasteland level. The manual for the game talks this up in terms of having to be very careful with your resources, like you’re playing a survival simulator, but the “survival” parts are made of pure tedium rather than anything enjoyable or challenging as you slowly make your way to each mine to get food to sell for more fuel so you can get to the next one, hopefully not making a wrong turn along the way so that you actually have enough fuel to make it.

In general Mad Max is boring and frustrating to play, and perhaps due to the three films’ various distribution and production companies the game lacks personality, opting for vague evocations of elements from all three films instead of offering a focused depiction of events and characters from one. You get Warner Bros.’s old photographic cover for Mad Max 2 as the game’s cover, but portraits of both Mad Max 2 and Thunderdome characters make an appearance. No one is mentioned by name except for Max himself. This was a bizarre combination of elements since Mad Max 2 had been originally released in the US under the title The Road Warrior (and even in the late 80s was far more popular in the US than both its predecessor and its sequel).

While calling the game Mad Max would have made for easier international appeal, the game was never released outside of the US. Yet licensing was clearly enough of a mess that outside of the box cover and the title screen, the game almost feels like it’s trying to hide what it is with its minimal in-game text and indistinct graphics (though for an NES game, the sound effects are in fact excellent). This would become more apparent in Mindscape’s next “Mad Max” game, Outlander.