CONTENT WARNING: This game is about real life serial killer Albert Fish, and it uses the names and likenesses of two of his real victims. It also deals with domestic abuse and child abuse.

Born May 19, 1870, Hamilton Howard “Albert” Fish became one of the most notorious serial killers in the history of the United States, himself saying that he may have killed, cannibalized, and molested hundreds of children in his life before being executed via electric chair for the murder of Grace Budd on January 16, 1936. His family had a history of mental illness, including himself, and commonly participated in extreme sadomasochistic acts, including castrating one of his partners. His childhood was oddly spent in an orphanage, where he was exposed to extreme acts of perversion and abuse. He was given many nicknames, including The Boogy Man, The Gray Man, The Moon Maniac, The Brooklyn Vampire, and The Werewolf of Wysteria. The names of most of his victims remain unknown.

In 2015, Jon Oldblood released an experimental horror game where you are cast into the role of Fish himself, but not in the expected, exploitative way. In fact, the game doesn’t make it clear for a long time who this character is, but anyone with passing familiarity to the case will quickly piece together the protagonist’s identity. Connecting the game with the horrific legacy of Albert Fish isn’t an attempt to latch onto something to be shocking and edgy for attention, but to build on the game’s themes and to best accomplish its main goal: to make the player as uncomfortable as humanly possible. It succeeds very, very well. There is a purpose to that uncomfortable atmosphere too, forcing the player to consider some very cutting questions about themselves.

The game casts you as Hamilton, a scared child who talks with a voice in his head, sees a mysterious “Gray Man” one day while trying to leave a shed, and is commonly abused by his horrible father. His brother is an extreme masochist who is tied up to avoid harming himself, and his mother is a psychological mess who commonly goes on insane tangents and jumps from loving to scornful at the drop of a hat. His life is terrible, but he is directed by a stranger named Albert in his backyard to Michael, an “angel” that wants him to deliver a message to his father. He also speaks with Grace, a faceless girl who can calm him down, but her true purpose and desire is completely unknown at first.

Off the bat, the game is loaded with hidden messages. With knowledge of the real Fish case and an understanding of hexadecimal code, a lot of the numbers scattered around can be deciphered, revealing connections to the Fish case. Of course, some much more clearer connections also get brought up in the game proper as well, such as the meeting with the horned bear guardian allowing a few dialog options that directly reference the case. There are also a lot of reoccurring symbols that connect to Fish, including his “instruments of hell,” the hexagons placed everywhere, and the needles you can use to calm yourself down (Fish was found with dozens of needles jammed into his body).

These connections are important, but it’s not a biographical title by any means. There’s many changes, the biggest coming from a lack of many of Fish’s family, the father being the abuser, and Billy appearing as a character both older than he was when he was murdered, and meeting Fish apparently as a child. Oldblood mentions in discussions on the game’s Steam forums that these changes were partly made to avoid making an exploitative title, and because the real events were far more horrific in his eyes. These changes also create a stronger story structure and blend real events in the narrative with events that are only in Hamilton’s deteriorating mind.

The game tries capturing depression and anxiety within the main character’s perspective. The entire game is shown through Hamilton’s eyes, warped and horrific. You move around left to right, can move to new areas via clicking on arrows and doors, plus pick up items here and there and talk with characters the same way. It’s the usual point and click adventure stuff, but with no real puzzles to solve. This is good, because puzzles would add little here. The focus is entirely on atmosphere and making the player reflect on what they’re doing, even throwing in a few moments where the game doesn’t address Hamilton as much as it addresses the player.

Hamilton’s conflict is related to his supposed fate. If you want, you can try to defy the dark path Hamilton will end up on as Albert, and there are ways presented to change the direction of the narrative, but the game does throw in a few non-choices to try and condition you to think that you can’t escape the grim ending. It also tosses out txt files on your desktop that reflect on your play style in game, just to screw with you a little. Be glad that’s one of the few ways it screws with you via meta methods, Oldblood had to remove several features that went poorly with play testers, including the game starting up invisibly at random moments just to talk with and freak out the player.

The themes of fate and mental illness are well handled, as is the meta theme of player choice. How you choose to play, embracing Hamilton’s future like a cartoon character, or reacting like an actual human with empathy, does effect the ending. At the same time, there is usually not a happy outcome, and the game does force you into situations where you have no choice but to commit horrific acts. It will also make sure it’s as uncomfortable as possible through the sickening sound design. Speaking of which, a few tracks in the game played backwards actually contain messages to the player, mostly too obey and kill and such other lovely things. There are short flashes of numbers, code, and images at random moments too, so you can spend a good while trying to capture those messages in screenshot or video to decode them. Otherwise, is adds a touch to the maddening mood.

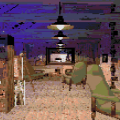

The art style is very unsettling and makes great use of the uncanny valley. All the characters have a design not unlike old American art, slightly deformed to make them threatening and unnerving. The world around Hamilton also mixes some truly beautiful natural landscapes, rotting buildings, and vile looking halls. Hamilton’s house is loaded with disturbing paintings and a creepy red color scheme, while areas like the meeting place for Micheal are given a peaceful green. There’s a clear atmospheric divide between areas at start, but as things escalate, more digital decay effects pop up more often, and new areas gain grosser color schemes. Once you reach the warehouse, the game has its most disturbing sequence, including one truly horrible part involving a mess of moving gears.

This is not a game for everyone, especially those dealing with issues brought up in the game proper and those uncomfortable with media that uses real world killers and victims as characters, but Masochisia is something worth defending. It’s a daring and bold experiment, tackling very grim ideas without flinching and forces the player out of their comfort zone. It’s incredibly well executed, outside some annoying jump scares after the warehouse sequence (the ones before are far fewer and better paced out). Few games can so effectively get under one’s skin, and the addition of a real world serial killer is used well thematically and brings up proactive questions about the nature of choice. Most importantly, despite everything that happens in this game, it makes two things very clear.

Hamilton, a character based on a real human monster, despite everything he went through, is not completely blameless for his horrible actions.

And neither are you.