- Metal Gear

- Snake’s Revenge

- Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake

- Metal Gear Solid

- Metal Gear Solid Integral Staff Commentary

- Metal Gear Solid (Game Boy Color)

- Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty

- Document of Metal Gear Solid 2, The

- Metal Gear Solid: The Twin Snakes

- Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater

- Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots

- Metal Gear Solid: Portable Ops

- Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker

- Metal Gear Solid V: Ground Zeroes

- Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain

- Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance

- Metal Gear Touch

- Metal Gear Acid

- Metal Gear Acid 2

- Metal Gear Solid Mobile

Version comparisons co-authored by Kurt Kalata

“Operation Intrude N313: Infiltrate the enemy fortress, Outer Heaven, and destroy Metal Gear, the final weapon!”

By late 1980’s, Konami were a well known entity in the broad culture and industry that grew around the new medium of video games in Japan. Starting out making successful arcade games like Frogger, Time Pilot, and Contra, the company quickly jumped into the burgeoning world of home consoles, following the success of devices like the Famicom, Commodore 64, and MSX. More games needing to be made meant more people needed to make them, so the company staffed up quickly. College graduates were scooped straight from graduation and placed on projects, no matter their grasp of Assembly, C, or BASIC. These new hires were often handed a brief proposal for a game idea, often following some trend or demand, and given a short amount of time, sometimes only a handful of months, to put everything together.

Hideo Kojima was one such hire, brought into Konami to develop for the MSX platform. After working as Assistant Director on Penguin Adventure, a sequel to one of the company’s early forays into console development, he was promoted to Director for his next project and handed a proposal for a war action game, a popular trend at the time. Only, the game materialized with a very different design, one that emphasized evasion rather than confrontation. Initially dubbed “Intruder”, the name that was eventually settled on was “Metal Gear“, after the bipedal mecha that is of central importance to the story, when it was released in July 1987 for the MSX2 in Japan.

The change to stealth was inspired by technical limitations. The MSX2, while popular for games, was getting old by the time Metal Gear was developed, even as the standard was upgraded. The Famicom, just released two years later, was designed with games in mind. It gave developers the ability to put more sprites on screen, and importantly, to scroll the screen more smoothly. The kind of action games with contiguous levels not broken up into screens, like Super Mario Bros., were difficult to pull off with the same sort of intensity and smoothness on an MSX2 machine, built for a wider array of tasks. So Kojima, an avid film aficionado from youth, took inspiration from one of his favorites, The Great Escape, a 1963 film that fictionalized the real life account of British soldiers escaping from a German POW camp during World War II. After some convincing of higher ups, the military action game proposed transformed into something closer to The Legend of Zelda with the veneer of a Hollywood blockbuster.

The Year is 19XX. The place, Outer Heaven, a mercenary state hidden somewhere north of South Africa. The man, Solid Snake, a rookie for the special forces group FOXHOUND being sent out on his first mission. The mission, sneak into Outer Heaven, make contact with local resistance leaders, rescue hostages, and take out the mechanized menace, the nuke-launching Metal Gear. Hostages include Gray Fox, a fellow FOXHOUND soldier who went missing infiltrating the compound, and Dr. Drago Petrovitch Madnar, a world renowned mechanical engineer. Dr. Madnar’s daughter, Ellen, is also kidnapped in order to coerce him to work on the mech. Along the way, he encounters a series of maniacal bosses, each one themed around what weapon they use, as he attempts to discover just who the “legendary mercenary” behind Outer Heaven is. Little does the rookie know what truths and lies awaits him on his mission.

The original MSX2 game opens with Snake infiltrating by water, pulling himself up on a dock, and making contact via radio transceiver, the primary way the story unfolds and how the rookie keeps in contact with the game’s slate of characters. Big Boss, the leader of FOXHOUND and Snake’s CO, keeps the rookie focused on his mission. Others help him keep track of other things. Kyle Schneider offers guidance in navigating the buildings of the compound and Diane, a punk rocker turned intelligence officer, gives him the run down on enemies. Later on, Jennifer, a resistance member who has infiltrated the medical staff, points Snake toward weapons and unlocks doors. The presentation of these characters, however, is bare, and much of this is covered in the instruction manual, rather than coming up during gameplay. The only other dialogue is when Snake rescues a prisoner, who might point out some ammo cache or access card before disappearing. Despite all of the surrounding characters & story, Snake himself remains quiet.

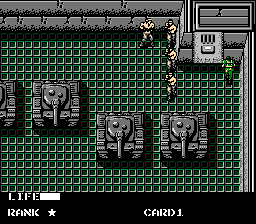

Snake starts with nothing but a pack of cigarettes in his inventory, finding what equipment he can on site. The first screens will likely involve a neophyte player getting confused and startled as they, armed only with a punch, try to eliminate the enemies they see. When Snake is spotted, an exclamation mark appears over soldiers’ heads and they go into alert mode, running around, firing randomly, and rushing at him until he leaves the screen. Soldiers are color coded, with green being the easiest to defeat while blue and red enemies are more elite and faster. They also have a literal line of sight. It’s not uncommon for Snake to graze right by a soldier undetected, only to be caught by another enemy or a camera across the screen.

Snake gathers six weapons on site, including a grenade launcher, plastic explosives, and land mines, and these weapons are important for the game’s boss fights. The rookie takes on all manner of humans and machine as he makes his way through Outer Heaven. Human bosses are given comic book style names, like Machine Gun Kid or Fire Trooper, with simple patterns to dodge and specific weaknesses to weapons. The military hardware he takes down are similarly silly too, like a Hind D sitting on a rooftop (at least in the MSX2 version) and a bulldozer trapped in an inexplicably narrow hallway. As you proceed through the game, you must rescue POWs; save enough and you’ll increase your rank, which in turn will extend your maximum life meter.

If you’re only familiar with the later Metal Gear Solid games, these bosses and enemies and mechanics and plot, it’s remarkable how familiar the game feels. The action unfolds through a series of rudimentary set pieces; a room of invisible lasers requiring a pair of infrared goggles to navigate, a desert full of tricky scorpions who can poison you, another room with an electrified floor and a switch vulnerable to rockets on the far end. At one point, Snake even has to get captured to make progress. Today, such an adventure would be constructed with polygons and global illumination and motion capture, but here it’s presented with just plain, square-ish, unraytraced pixels.

The super-serious and, at times, madcap antics that the series would be known for established themselves here and loudly. Just looking at its box art, it’s a game that wants to be seen as a macho action flick, full of masculine bravado, geopolitical gravitas, and taught military work. This is also a game where its super serious spy can find a cardboard box and use it to hide in plain sight from enemies. It’s also a game that subtly embodies the sexist attitude towards women common in the blockbuster flicks it is inspired by, something of a running theme among Kojima games. Diane, the operator meant to assist Snake, is portrayed as taking a shower or out shopping when he calls. Another woman, Jennifer, a resistance leader, is described as “proud” and is only interested in people “high class” enough for her, literally meaning Snake has to achieve a certain rank before she responds. The melodramatic, goofy, and infuriating feel of Metal Gear was present from the beginning of the series.

All this said, there is no denying that the game is rough to play in ways that are taken for granted now, and some of its mechanics inspire frustration. Each key card is a separate listing in the inventory and a higher number card doesn’t grant access to anything below it so the player has to clumsily flip through every card and rub Snake up against each unlabeled door. Snake can only move and shoot in four directions, but enemies can move and attack at any angle, their funky and random patterns making it hard to anticipate their movements when in alert mode, and getting damaged is pretty much expected when caught. It’s not a long game, but often the way forward isn’t clear, leading to a lot of wandering around. In what would become a series tradition, backtracking is required and feels more like padding than something organic. Even when it’s not necessary, other situations can put the player into a position where it is necessary. Running out of ammo, restocking health-giving rations, needing an antidote after getting scorpion-stung, or reaching a boss without the correct weaponry means a tedious jaunt back to stock up of the necessary item. Time has not been kind to the designs of this era, this game included.

Taking a step back, and really looking at Metal Gear when it was made, it’s clear that the game is trying to punch above its weight, an admirable aspiration when resolutions were a fraction of what they would become and color were deeply limited by what screens were even capable of displaying. It almost feels like a licensed tie-in game – but much more competent & thoughtful than that comparison implies! – to a movie that was never made, some lost blockbuster that Kojima himself might have wanted to write & shoot. Other games of the time, such as Metroid, Sweet Home (itself, a game based on a film), and Blaster Master, shared the same sense of vision. These were games that were pushing beyond the arcade, beyond the simple, flashy loop of high score chasing and quarter munching. The people making them were taking inspiration from other mediums to expand the possibilities of their own. They were asking the question of “what *can* a game be” instead of “what is a game”. The people who made Metal Gear had their sights set far past the limitations of the moment.

The game was a success on the MSX2, even getting a European release (with some questionable localization decisions, such as half of the radio calls missing). The success inspired the higher ups at Konami to commission a version for Nintendo’s successful console. According to Masahiro Ueno, a programmer with a long history at Konami, the porting team was given three months to make it happen, an intense deadline even with the source code provided. As a result, this version of the game feels rushed, with features and items missing and levels trimmed down, split up, or cut entirely.

The biggest, most noticeable changes is the drastic reworking of the game’s structure. Many of the actual maps are the same (or similar) but their locations have been changed, and the NES version has several new areas. The MSX2 version starts off as Snake swims into the base and begins directly inside the first building, while the NES version has you go through several screens in a jungle. The MSX version has three buildings, while the basements from these areas were transplanted and now inhabit their own building. Also added is a small jungle/desert area, which feature a Zelda Lost Woods-style puzzle of repeating screens. Both versions have trucks that can transport you to different parts of the game. Since the game world in the NES version is actually a bit bigger and less linear, there are more trucks. The NES version adds a new item called the Iron Glove, which lets you break hidden walls rather than using plastic explosives. The MSX2 version also has a section where you need to find a parachute to find one of the key cards. The NES version removes this segment, so the card was moved elsewhere.

Many changes seem to have been the result of memory limitations. The MSX2 version has enemies on the roof that fly around, while they act like regular soldiers in the NES game. Similarly, the dogs in the MSX2 version have their own original AI routines but in the NES version just act like any other enemy, just without guns. The MSX2 version has you fight a (completely stationary) Hind D helicopter, while the NES version has you fight the Twin Gunners, who man posts at the top of the screen and fire Gatling guns.

Most egregiously, you never actually see a Metal Gear in the NES version! In its place is an enormous supercomputer, which you need to blow up using bombs. There are guards in the room, but once you take them out, it’s easy enough. In the MSX2 version, you have to place explosives on each side of the Metal Gear in a specific sequence. In the meantime, you’re attacked by laser guns on the walls. This produces a weird little video gamey plot hole. The whole idea of saving Pettrovich is so he can tell you how to set the explosives. Since the order of explosives doesn’t matter in the NES version, technically there’s no reason to save him at all! However, talking to him after saving his daughter Ellen is a trigger which makes the super computer vulnerable. If you try to blow up the computer without talking to him, it will be invincible.

Stopping the alarms in the NES game seems to be a random process. Sometimes it’ll stop if you leave the screen, sometimes it doesn’t. In the MSX2 game, there are two sets of alarms. The higher alarm phase, indicated with double exclamation points by the enemies, are triggered in certain circumstances where you’re not directly spotted by an enemy soldier, like getting spotted by a camera. During this double alarm phase, enemies will chase you anywhere and won’t stop until you’ve disposed enough of them. Also, in the MSX2 version, if you punch enemies, they will potentially drop ammo or rations, giving you an incentive to sneak up on them. This element is completely missing from the NES version.

Near the end of the game, when Big Boss radios to tell you to stop the mission, in the MSX2 version he says to shut off the MSX. This cool little fourth wall break is missing from the NES version, where he just says to quit the mission. It’s neat that this actually predated its used in Metal Gear Solid 2, when the AI Colonel tells you something similar.

The NES version has lots of stupidly designed rooms where it’s impossible to avoid being spotted when entering. The MSX version actually changes the position of the soldiers depending on where you enter the room. For example, if you enter from the right, there might be three enemies patrolling. If you enter from the left, there might only be two, so you aren’t spotted immediately on entering, or least giving you a bit more time to react. Also, in the NES game, the cameras have blind spots directly beneath (i.e. right next to) them. This doesn’t work in the MSX2 game, so avoiding cameras is a much harder process. The NES version also has a bug which resets certain elements on the screen when you enter a secondary screen (weapons, items or transceiver). This includes the position of the bosses. It can also be used to remove the pitfalls. The hole itself will disappear, but the tiles itself are still deadly.

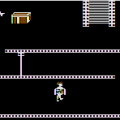

Visually, the games are similar, but the MSX2 version has some added coloring and detail. Primarily, the waterways are colored blue in the MSX2 version, while they’re grey in the NES version, so they look more like concrete. There are added bits of polish in the MSX2 version, like the bricks on the pitfalls, which are just pure black holes in the NES verson. The NES version has an introduction sequence showing four people parachuting into the jungle, though it’s never clear who the other three characters are. This scene is shown again at the ending when the facility explodes. Meanwhile, the MSX2 version has an extra scene at the ending where Solid Snake outruns an explosions, Hollywood movie-style.

The main soundtrack is different, too. Since the NES version has more outdoor sequences, there are actually two types of sneaking music, for indoor and outdoor. The MSX2 version also has two sneaking themes: the main one, and the one used in basements. In both games, the boss theme, final room, final boss, and game over themes are identical, but the ending themes are different.

The English NES translation is infamous for some awkward phrasing, including the famous “I feel asleep!” and “The truck have started to move!” lines that became memes in their own right for kids of the 1980s & 90s. There’s also a rather bizarre mistranslation on the roof of the first building. Big Boss explains that you need a Bomb Blast Suit to get past “window barriers”. This should be “wind barriers”, which makes more sense given how you seem to get blown back when you try to pass. Some of the clues given by the codecs are wrong in the NES version, like where to find the Gas Mask. The NES game refers to your group as “Fox Hounder” which at first seems to be a mistranslation, because Metal Gear 2 (and all subsequent games) calls them “Fox Hound”. This was actually present in the Japanese MSX2 game though – spelled out in English characters, actually.

Now, the ultimate question: which is better? Kojima has long disavowed the NES version, but it’s probably because he didn’t work on it. A lot of the changes in the NES version obviously stemmed from technical issues, whether due to tile, palette or memory limitations, but a lot of it was things that the programmers just couldn’t (or didn’t) implement.

Despite some of the noticeable omissions in the NES version, some of works in its favor. Metal Gear is already hard enough, and some of the changes with the enemies and cameras make it more manageable. Snake’s Revenge actually retains many of the elements of the original MSX2 game that were removed from the NES port, like punching soldiers to get items, the heightened alerts, the checkpoints, and palette change when using the goggles. It even has an assault against an actual Metal Gear at the end, although you destroy it by remote controlled missiles instead of explosives.

This NES version formed the basis for two other ports, both for home computers in 1990. Metal Gear on the Commodore 64 looks, sounds, and plays as expected. The chunky vibes of the SID chip does its funky work for the sound and music while the visuals are simplified and less detailed than its predecessors. An MS-DOS version doesn’t fair much different. There are some unique flourishes, like a cutscene for Snake entering an elevator, a few added stills, or the crumbling skeleton that enemies and Snake leave when they die, and it looks decent in EGA, but it otherwise feels similarly limited, especially with only PC speaker sound. The game can be tricky to finish, with a late game bug potentially wrecking all progress.

In 2004, the MSX2 version was ported to mobile phones of the time, exclusively in Japan. It adds in an easy mode, a boss rush, and an improved translation with different names for the characters, but otherwise plays and looks the same as the original. Metal Gear Solid 3: Subsistence included this version as a bonus, and this is the version that has been included in other collections, like MGS HD Collection on the 360 and PS3 and the Metal Gear Solid: Master Collection Vol. 1 for modern platforms and PC. This marked the first time the original game, in its intended form, officially reached North American shores.

The most modern and most unofficial port is for the Amiga. Rumors of a port to the venerable computer system were teased at the time, but nothing materialized. Then, in 2021, a homebrew developer h0ffman did what Konami didn’t, bringing the game to the Amiga. Based on a decompilation done some years earlier, the port is excellent, practically matching the MSX2 original and more. It runs at a higher frame rate, and it include new versions of the original game’s music, alongside sound effects lifted from Metal Gear Solid. The higher frame rate can lead to some accelerated enemy patterns but it is otherwise remarkably authentic. The original MSX2 sounds and music are included, as well as a selection of translations to choose from. The most unique addition of all are character portraits on the transceiver screen, with some very platform-appropriate looks to Solid Snake, Big Boss, and other characters in the game. They give an already amazing port some extra Amiga charm.

Even as limited as Metal Gear is – Snake can’t even crawl! – it remains unmistakable for the series it spawned. What came later only became more “solid” as things developed, but what the series would become, cardboard box and all, was in its DNA right from the start. Long running franchises like Final Fantasy or Call of Duty, rarely follow a solitary vision, and can change their identity as the marketing department demands. Their names are more about brand recognition. But Metal Gear has remains unique for a relatively consistent vision – a vision that came from more than just the man whose name gets plastered on the box – which is a rare accomplishment in this fickle industry. As Konami returns to the series and the company gets the hype train chugging once more for remasters and collections, one has to wonder what a remake of Metal Gear would look like now, with so many of the folks who worked on it, scattered to the winds in this business of video games.

Thanks to John Szczepaniak for the computer comparison screens. Thanks to Vintage Computing for the NES advertisement.

Screenshot Comparisons

Opening

Transceiver

Tank

Roof

Elevator