In March 1986, Nintendo released the Famicom Disk System, as a way to get around of the technical limitations of ROM cartridges. Early Famicom releases tended to be pretty simple arcade-type games, but the expanded storage capability and ability to save games allowed for more complex titles, similar to what could be found on home computers. The headlining title was The Legend of Zelda, the seminal game that combined fantasy role-playing with colorful characters and huge worlds.

Obviously Nintendo needed more than one title to sell its system, so they worked on developing a few other titles that also played to the capabilities of the system. One of the other most popular was Metroid, directed by Satoru Okada, who previously worked on Balloon Fight and Wrecking Crew, and later went on to helm Kid Icarus, Famicom Wars, the first Famicom Detective Club game, and Super Mario Land. Much of the design of the game is attributed to Yoshio Sakamoto, who had previously worked on Donkey Kong Jr., as well as Balloon Fight, and Wrecking Crew with Okada. Other team members including Hirofumi Matsuoka, a graphic designer who later went on to direct Mario Paint; Hiroji Kiyotake, the artist credited with all of the original designs; and Makoto Kanou, the scenario writer.

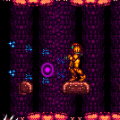

While the open-ended adventuring spirit was similar to Shigeru Miyamoto’s Zelda, it differed in two major ways: first, it used a side-scrolling perspective, and second, it featured a science-fiction theme, heavily inspired by Ridley Scott’s 1979 movie Alien. (It was also coincidentally released in the summer of 1986, around the same time as James Cameron’s Aliens sequel. The developers didn’t know it at the time, of course, but Metroid (along with Zelda) codified many genre conventions, and its influences can be felt decades later.

The game stars Samus Aran, an intergalactic bounty hunter wearing a cybernetic suit, exploring the underground caverns of the planet Zebes. This hostile world is the home base of a group known as the Space Pirates, who have stolen samples of a mysterious (and incredibly dangerous) creature called a Metroid. These can be bred into weapons of biological war, so it’s of upmost importance that Samus is able to stop them.

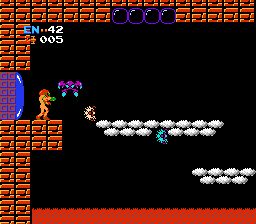

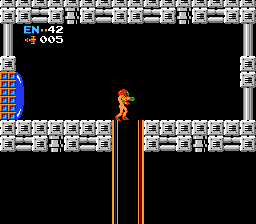

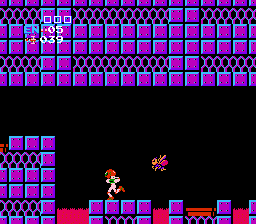

At the outset of the game, Samus is actually incredibly underequipped, despite being the last hope of the Galactic Federation. You have an incredibly short-range bullet attack…and that’s it. However, the game subtly teaches you in the way that you must hunt and upgrade your powers in order to fully explore Zebes. Most arcade games have trained players to walk to the right – in Metroid, you can only proceed a few screens before reaching an impassable area, a tunnel which Samus is unable to squeeze into. So instead, you need to go back left, past the starting point, to obtain an upgrade called the Maru Mari (“maru” means “circle” in Japanese), which allows Samus to morph into a spinning ball, and allowing you to roll through the tight passage back to the right.

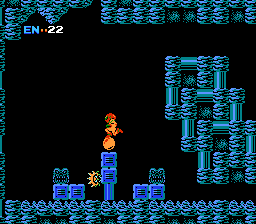

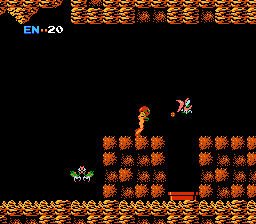

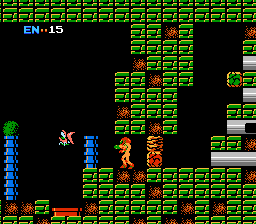

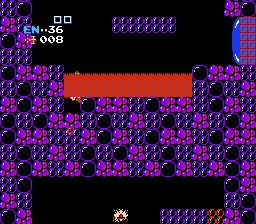

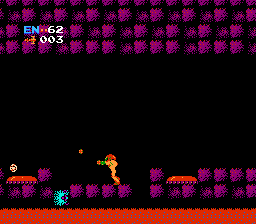

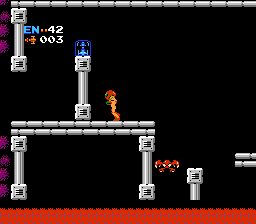

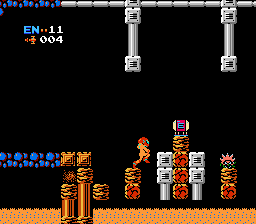

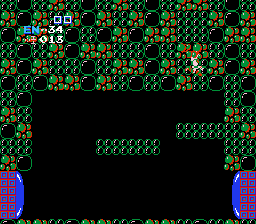

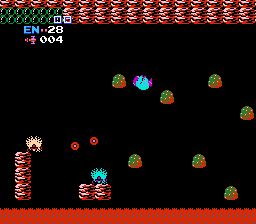

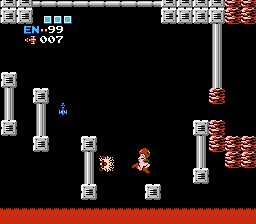

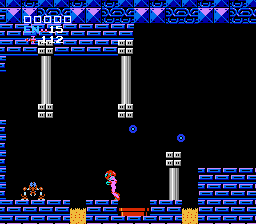

This is only the first step in exploring more of Zebes. The planet is divided into five areas: Brinstar, the opening area; Norfair, an area filled with lava; the two lairs for each of the games’ bosses, the spiked turtle-esque creature Kraid and the dragon creature Ridley; and finally Tourian, the final area, which contains both the Metroids and the Mother Brain, the leader of the Space Pirates. You transition between screens through bubble-shaped doors, which open when you shoot them, though some require being plastered with missiles before they’ll unlock.

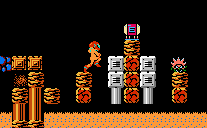

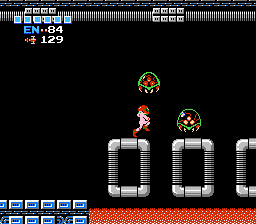

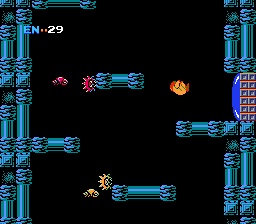

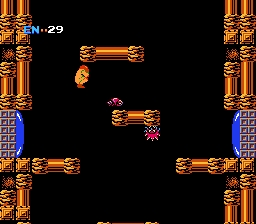

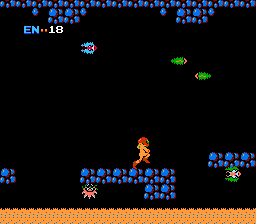

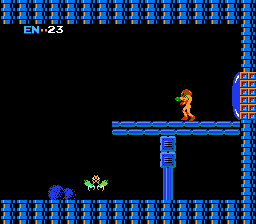

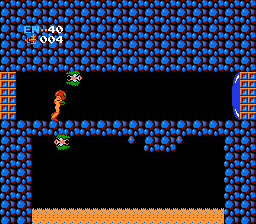

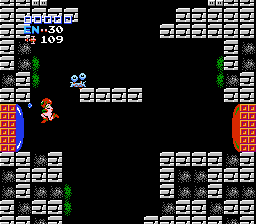

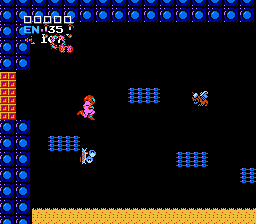

Zebes is filled with a variety of distinctive enemies, many of them vaguely insect in appearance. One of the most common are little spiked creatures that crawl around the perimeters of platforms, which take on multiple forms throughout the game. Also present are shelled creatures that fly back and forth, which are invincible to most attacks; bees that spawn infinitely from pipes; fire breathing dragons; and tiny little buggers that swarm in great numbers. It’s a testament to the game’s visual design that they all remain unique and distinctive given the limited graphical power of the NES.

Other than finding and destroying the games’ bosses, so you can enter the final level, you’ll need to find other assorted items in order to beat the game. Most of these are found in the claws of Chozo Statues, mysterious bird-like creatures, whose lore is expanded on in subsequent Metroid games. One of the most important things to find are missiles, which are not only more powerful than your regular weapons, but are required to open red doors. Each missile upgrade increases the amount of ammunition you can store, up to 255. Just as important are bombs, which let you destroy certain blocks on both the floors and on the walls. With proper timing, you can also “bomb jump” by using the explosions from detonated bombs to propel you upwards, something which takes a lot of practice but can be used to bypass certain areas of the game. There are also the high jump boots (expectedly, these make you jump higher) and the Ice Beam, which lets you freeze enemies and use them as temporary platforms to jump to higher areas.

These are the only items that are (technically) required to beat the game, but there are other things to find that will greatly help your journey. One of the most important of the Varia suit (a mistranslation of “Barrier”), which halves any damage you receive. There’s also the Wave Beam, which travels in a sine wave pattern and is much more powerful than your other main weapons (save for missiles) as well as the Long Beam, which simply expands the length of your main weapon across the entire length of the screen. Also, by default, you can only store up to 100 energy (health) points, but Energy Tanks extend your capacity by another 100, eventually expanding your health to 699 points, if you find enough of them. There’s also a fun ability called the Screw Attack, which effectively turns Samus into a buzzsaw during somersaults, shredding anything that comes into contact. However, you’re definitely going to want to explore as much as possible before beginning the final assault on Tourian, because it’s incredibly difficult. So, you’ll need as much health and missiles as possible to even think about destroying Mother Brain.

Of course, one of the major issues with Metroid is that Zebes is an incredibly large, confusing labyrinth. There’s no real direction of what to do or where to go, compounded by the fact that many of the rooms and corridors look identical, making it very easy to get lost. This was long before games included auto-maps, so the game expects you to draw your own (or buy a strategy guide). Furthermore, many of the power-ups are hidden and there’s no indication of which bits of scenery can be destroyed, requiring that you bomb almost every block you can in hopes of finding a hidden passage. This isn’t just to find bonus stuff, even mandatory items are hidden in obtuse places – the Ice Beam, for example, is found beneath a fake lake of acid.

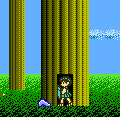

Even though it can be intimidating, it’s certainly not impossible. One of the advantages of the game’s level layout is that it’s neatly divided into horizontally and vertically scrolling areas, allowing it to be easily mapped into a grid. Plus, after playing for awhile, you grow some intuition of where hidden passages might be. Find a dead end, for example? Bomb everything, everywhere!

Samus is actually pretty fun to control too. There are some control limitations – you can’t duck, so to defeat crawling enemies, you either need to use bombs or use the Wave Beam – but the fluid, acrobatic jumps are satisfying, which is especially useful during the many areas where you need to scale vertical caverns.

Still, there are other areas where Metroid shows its age as a product of the mid-80s, or otherwise just plays cruel tricks on you. For example, the game lets you save progress, either writing to the disk (for the FDS version) or with a password (the NES cartridge version). However, neither version records your health (only your maximum number of energy tanks), so you’ll always begin each game with a measly 30 energy points. Luckily, there are certain pipes where enemies quickly respawn, so you can camp out there and farm health from their destroyed corpses until you’re maxed out. (The FDS version will also only start you out at Brinstar, at the opening of the game; the NES version is nice enough to stick you at the entrance of the area you left off in.) There’s no save points, either, so you either need to intentionally kill yourself or use a command via the second controller to forcibly quit the game.

There’s no status screen either, nor is there any way to switch weapons. For example, you’ll probably be spending most the game using the Wave Beam, because of its strength. But for the few areas where you need the Ice Beam (including Tourian), you can’t just switch to it, you’ll need to run back to any of the locations where it’s located in order to equip it. You generally don’t want to use the Ice Beam when you don’t need to because it’s actually weaker than your main gun – one hit to freeze, and then another to unfreeze, but it only registers the same amount of damage as one regular shot even though you hit it twice.

There are a few areas where you can fall in lava and it’s basically impossible to get out, requiring that you sit and wait until your life drains. Plus, there’s a “fake” boss in Kraid’s Lair, which may lead you to believe you’ve beaten his area. The clue is that this is easier than the real ones, and beating the actual boss will also grant you a significant missile bonus.

Still, there’s a lot to like about the original Metroid, even in spite of its many improved sequels and subsequent games that were inspired by it. Though the visuals are stark – all of the backgrounds are just dark black – each of the five main areas are visually distinct, each with their own music theme. The triumphant Brinstar theme sets the theme for the rest of the game, though the remainder of the songs run between low-key (the Norfair tune) and actively terrifying (Kraid’s lair) in ways that few NES tunes are. The music was composed by Hirokazu “Hip” Tanaka, who, along with Koji Kondo, is one of Nintendo’s most well-known composers, with his works including Mother, Kid Icarus, Tetris, and Dr. Mario. Even the sound effects are distinct and memorable, ranging from Samus’ footsteps to the strange enemies that noises make when they’re hurt, to the “FWOOP” noise of opening doors and sizzling sound of the Screw Attack.

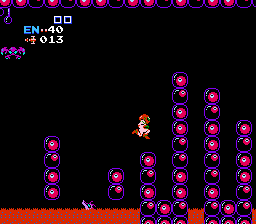

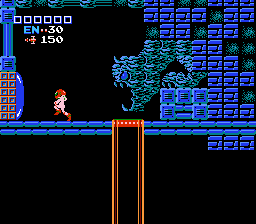

Plus, many parts of the game just incredibly scary, in ways that subsequent games softened up. For starters, there’s the eponymous Metroid itself. Though its design has become iconic among video games, the manual doesn’t actually show what it looks like, making it all the more mysterious at the time of its release. When you do enter Tourian and see these jellyfish-type creatures, swarming you and quickly sucking your life away, it’s a moment of shock and terror almost unlike anything in any other NES game. It’s doubly frightening if you don’t know how to beat them – you can technically ward them off via bombs, but the only way to kill them is to freeze them then unload a torrent of missiles.

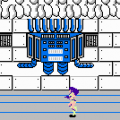

The final battle with Mother Brain is also harrowing. While technically she is defenseless, you need to shoot a large number of missiles into her jar, while avoiding the many flaming projectiles being shot out of her defense systems, while avoiding being tossed into the lava below. Assuming you do beat her (without running out of missiles), it triggers a self-destruct sequences, where you need to put your platforming skills to the test as you escape through a large, vertical cavern, leaping between tiny platforms, before the timer runs out. None of the later Metroid games can quite match this level of intensity.

Metroid is also infamous for its glitches, particularly the way you can slowly work your way through otherwise solid walls and ceilings to reach otherwise inaccessible areas. Of course, the game wasn’t designed with these in mind, so you’re basically entering “junk” data of the game’s map, so there’s nothing really important there but various rooms and enemies. But it’s sort of fascinating to think there’s a mysterious area outside of the game’s boundaries, especially since magazines at the time hyped up these areas as hidden worlds, of sorts.

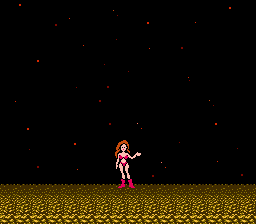

Of course, there’s also the game’s most famous twist – you get different endings based on how quickly you beat the game. If you complete it under a certain number of hours, then Samus will take off their helmet, and reveal themselves to be a woman! (Even though the manual explicitly refers to Samus as a male, even in the Japanese version.) As an added bonus, with even quicker completion types, Samus will take off her whole outfit and reveal herself in a bikini, which was an even bigger shock. Obviously, this has become well known in the years since, though it was spoiled in various ways even at the time – many magazines revealed it in their cheats sections, and even the Japanese commercials indicated it by casting a woman as Samus.

Metroid was released in North America about a year after the Japanese FDS original. In the intervening year, technology had improved to allow larger ROM space, though some changes had to be made to accommodate the different format. Most notably, some sound effects and music used the additional FDS sound channel, so these needed to changed. The biggest changes are the title screen and the iconic “item get” jingle, which, in the NES incarnation, sounds a lot like a similar theme from Ys, which was released in Japan around the same time as the NES version hit North America in 1987. The redone sound effects are pretty good, and in some cases it’s improvement – the Japanese version featured a blaring siren during the escape scene after destroying Mother Brain, which is thankfully removed from the US release.

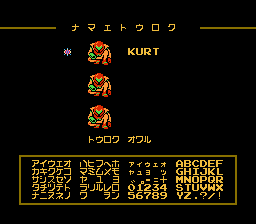

The Japanese version uses a save game system, with a menu similar to The Legend of Zelda – it even has a unique kneeling sprite for Samus not otherwise seen in the game. This could have been brought over for the cartridge release, but since it would’ve required battery backed-up RAM, instead a password system was implemented as a cost-cutting measure. This also allowed various cheats to skip ahead to various parts of a game.

There are a few other tweaks too – some of the enemy behavior is simplified in the ROM version due to differences in random number generation, there’s some extra slowdown in various areas (particularly in Tourian), and there are some extra glitches that cause certain tiles to be miscolored. Plus, the final battle with Mother Brain is made more difficult since there’s an extra piece of indestructible glass on her platform, making it impossible to get right next to her and attack.

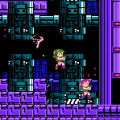

But the biggest change is the ability to play as Samus without her suit. Normally this is done by getting the appropriate ending, but there are assorted codes – particularly the JUSTIN BAILEY password – that let you start the game without the suit, along with assorted power-ups. There’s a long running urban legend that “bailey” is Australian slang for a swimsuit, effectively making the password mean “Just in bailey”, or “just in a swimsuit”. This actually isn’t true, and the fact that the password spells actual English words is just a coincidence. (There are a lot of these in assorted NES games.) The only hard-coded password is NARPAS SWORD, (“Nar Password”), a reference to Toru Narihiro, the programmer who converted Metroid to ROM format. Anyway, Samus’ hair is brown in the ending, but it changes in-game, depending on whether you have the Varia suit or whether you’ve enabled missile fire.

Metroid might be hard to go back to for gamers accustomed to newer games – for anyone wanting to experience the “story” of this game, there’s always the GBA remake, Metroid: Zero Mission – but its historical importance can’t be denied, and even compared to its contemporaries like The Goonies II and Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest, it still holds up fantastically well.