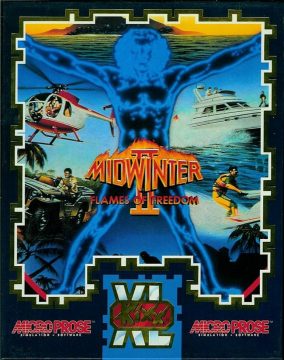

Midwinter II: Flames of Freedom (also known as just Flames of Freedom which makes sense given the change in setting) abandons the first game’s snowy landscape in favor of a sunny African setting: the impact winter has ended, the island of Midwinter was reclaimed by the ocean and its inhabitants moved south and established themselves on another island called Agora. There is, of course, still an evil empire that needs to be stopped but Flames of Freedom changes up the formula in significant ways.

Gameplay-wise, the biggest departure from the original Midwinter has to be the lack of recruitment mechanics. Playable character in Flames of Freedom is not a guerrilla leader but a spy sent on a lone mission and while you still need to get people to follow your cause, this time you have to do it through sidequests and skill checks. The results are also different: instead of gaining another playable character, you can ask for favors – some NPCs might assassinate your enemies, others will be able to speak to important people on your behalf, give you shelter or sabotage enemy installations.

Like its predecessor, Flames of Freedom pioneers some gameplay mechanics that would years later find their way into mainstream gaming. The game abandons turn-based elements of Midwinter in favor of completely real-time exploration. Things that would require stopping, going out of action mode and picking a decision in the previous game can be now done with a press of a button. This includes not only approaching other characters, sabotage or shooting but also switching vehicle. When close enough to one, it’s possible to hijack it not unlike in Grand Theft Auto and similar games that became so popular in the 2000s, although with a small difference: playable character in Flames of Freedom doesn’t have to be on foot to do that: it’s possible (and often very useful) to leap from a car into a tank , jump out of a zeppelin to take control of a helicopter or make your biplane do a nosedive so you can now travel by a speedboat.

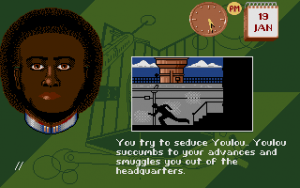

All those changes, of course, affect the game’s atmosphere and mood. The game isn’t as grim as its predecessor, trying instead to capture the style of action blockbusters. Midwinter was about being outnumbered, wounded, tired and cold but Flames of Freedom is about being a badass: your character will perform insane stunts, singlehandendly wipe out squadrons of tanks, escape from prison by seducing guards, assassinating military leaders and blowing up secret underwater bases. It’s a radical departure but it’s done very well – Flames of Freedom is as good at making you feel like an action hero as Midwinter was at making you feel unwelcome in its frozen landscape.

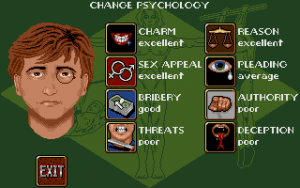

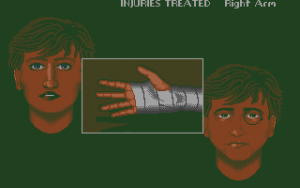

Flames of Freedom allows the player to create a custom character. The distribution of physical attributes has a noticeable effect on gameplay, although the skills generally fall into the category of those that help you with combat (e.g. dodging attacks, healing wounds) and those useful for extended on-foot travel (e.g. how fast you get tired and how long you need to rest ). Interpersonal skills provide less variety – they all work the same way, with an exception of sex appeal which can only be used on the NPCs of opposite sex and a select few skills like bribery or the aforementioned sex appeal that can be used to escape from prison. Generally speaking, it’s better to have a few on ‘excellent’ level, including at least one for prison escapes, than to be a jack of all trades.

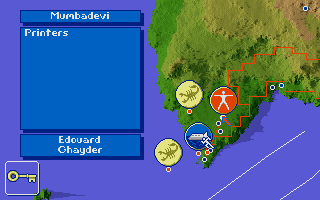

The game can be played either in raids mode or a campaign mode. In the former, player is tasked with liberating a single island on the map. To do so, he needs to perform a variety of objectives which usually consist of getting certain NPCs to help your cause, destroying enemy squadrons, assassinating NPCs or performing sabotage. The real meat of the game is campaign mode in which it’s necessary to stop Saharan Armada from reaching the island of Agora by liberating islands to slow them down and cause attrition and fighting the Armada’s battlegroups personally. Campaign mode requires quite a lot of strategic planning as reaching different islands takes different amounts of time and it’s also possible to liberate islands by cutting a supply line between them and the mainland by liberating islands inbetween – an extremely useful trick given the game’s rather unforgiving time limits.

When the mission begins, player is given a set of objectives, a weapon and a contact among the island’s populace. He’s then transported to the island by predefined means – sometimes you might start with a helicopter but it’s not uncommon to be given a much less universal speedboat or to get parachuted somewhere and be forced to continue on foot. Controls are predictably bad but the game thankfully allows setting automated routers for a more convenient exploration. The islands are patrolled by squadrons of enemy vehicles which will attack the player on sight – it’s good to destroy those as even if it’s not an objective, you will receive a reward for doing so. An interesting trick that makes it easier is jumping between the vehicles as once you take control of it, the enemies won’t be able to use it.

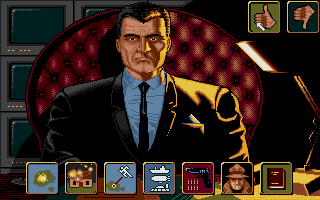

Approaching other characters allows you to initiate a conversation. Generally speaking, the NPCs will either offer you help, give you a sidequest before doing so or refuse to do anything until persuaded with the aforementioned interpersonal skills (your success depends both on your skill level and the NPC’s personality which determines how suspectible they are to different approaches). Occasionally, NPCs will betray you to the secret police – if that happens, you get thrown in prison and have to escape with either violence or skiils.

The game’s story takes place 60 years after the events of Midwinter. Former inhabitants of Midwinter now live on the island of Agora near the coast of Africa, neighboring 41 ‘Slave islands’ which were recently conquered by a cruel, expansionist Saharan Empire. After a series of political incidents, Agora finds itself on the brink of war it isn’t able to win and its leaders decide to weaken the enemy by inciting rebellion on Slave Islands. The plan, known as Operation Wildfire, is kept secret from everyone and to keep a low profile only a single agent – the playable character – is sent before the war begins. While the purpose of the plan is to hide Agoran involvement in those rebelions, somebody probably didn’t think this through as there seems to be a strong correlation between an island declaring independence from the Empire and the arrival of an Agoran superhuman who keeps leving behind a trail of crashed planes, exploded tanks and ruined military installations.

Graphically, Flames of Freedom uses as much green as Midwinter used white but overall looks very similar. There’s a bigger variety in both 3D models and 2D graphics but the 3D is still very blocky and low-poly. The game once again pushes both Amiga and Atari ST to their limits which unfortunately results in choppy framerate and low draw distance. Generally speaking, ports to different computers are comparable with their Midwinter equivalents, with the IBM release being overall best of the bunch despite the control device limitations. One advantage of the Amiga version has is the music: the game now has a soundtrack (although it doesn’t play in the action mode in which you spend most of the game) with an incredibly catchy main theme that sounds great on Amiga. None of the other versions come close, although PC Adlib sounds like a decent remix with its more relaxed, almost leisury feel. Unfortunately, DOSBox has problems handling it as while music sounds decent, the sound effects are just painful to listen to.

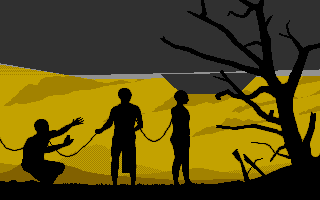

Predictably, the controls are a nightmare. While autopilot solves many problems, it isn’t useful in combat situations. The infamous acceleration by moving mouse up makes a return while looking up and down is performed with left and right mouse buttons. All the other actions are performed with function keys, with a contextual ‘special actions’ (e.g. talking to people or taking control of a vehicle) which would nowadays be assigned to ‘E’ or ‘F’ here invoked with ‘F1’. Worst of all, a single press of ‘A’ button in campaign mode will make Armada set out to attack Agora without even asking you for confirmation – this usually leads to a game over, with the words ‘DEFEAT’, ‘SLAVERY’ and ‘DESPAIR’ appearing over a picture of enslaved people.

Flames of Freedom can be an incredibly fun experience. It’s a bit less difficult and unforgiving than its predecessor, it has some quality of life improvements and it does so while keeping constantly innovating and without dumbing the game down. It is a flawed game for sure and its controls can be infuriating but its interpersonal mechanics, intense firefights, the ability to pilot multiple vehicles (from hot air balloons to jetpacks) and the unusual mixture of role-playing, action and strategy make it a worthwile experience. It’s one of those games that really deserve a good remake that would update the visuals and controls while keeping the depth of gameplay.

Both Midwinter games are examples of the amazing creativity the British microcomputer scene was capable of. They’re also pioneers of more than one modern genre, experimenting with different ideas and mechanics to pave the way for many games now regarded as classics. It’s not hard to see why they aren’t more well known today – they don’t look good, they’re not easy to learn and their controls are horrible – but they definitely need to be acknowledged as some of the most interesting action titles of their time.

Links:

Midwinter at Hall of Light

Flames of Freedom at Hall of Light

The Midwinter Report – a work in progress remake of the first game