When Ocean – creators of licensed “gems” like Hook, Jurassic Park and The Addams Family – first announced a new Mission: Impossible game (following an earlier 8-bit adaption by Konami) as a tie-in with the upcoming action blockbuster starring Tom Cruise, it was still a two-dimensional 16-bit affair, which looked suspiciously close to Flashback. Early previews even showed a jungle level next to some events from the movie. This version also showed off a detail that would be denied to the later reincarnation: Tom Cruise’s likeness.

But eventually the old generation would get shoved aside and by the time the N64 was nearing release, no one cared about the SNES anymore. So Ocean scrapped the whole sidescrolling approach and instead put their California branch (it is unknown where and by whom the SNES version was being developed) to work on the very first 3D stealth action game, with a release planned for summer 1997.

Tom Cruise in 16-bit.

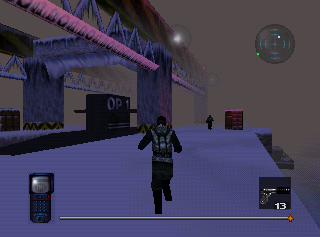

Mission: Impossible, as presented in 1997.

After some delays and difficulties the development team finally broke apart, and if it wasn’t for someone at Infogrames clinging onto the game, it would have disappeared just like the first draft. The French-based software house had recently bought out Ocean, and thus the code and assets were brought to Lyon, where a new team headed by Arthur Houtman (who later came to direct and coordinate Infogrames’ motorsport games department) was tasked with making something out of the unfinished project.

Needless to say, the game underwent some further changes of direction. Old screenshots show unused stages, or some that were implemented differently later. Ethan Hunt can be seen freely exploring Waterloo Station, for example, which became a pure sniper sequence in the final game. There is also a shootout at what looks like a diplomatic meeting between the USA and the Czech Republic, and there appears to be an action scene at an airport, which only appears in the ending. Most of the distinguishable changes are of cosmetic nature; the sidekick Candice Parker’s face got a makeover to make her look less nerdy, Ethan Hunt used to wear a few different outfits (including the white suit seen above and a wetsuit – he doesn’t swim in the final game) and used to look a lot more like Tom Cruise, even though the actor never gave his permission for his face to be used as reference. That wasn’t the only element the superstar objected to, either: He also had a problem with excess violence, and thus Hunt was to never kill an enemy. Well…

…that didn’t happen.

Just as the developers took liberties with Cruise’s wishes, they didn’t tie the game slavishly to the movie, either. It follows the same basic plot points – the mission in Prague, Ethan being branded as the mole, dealing with Max and discovering Jim Phelps as the real traitor – but beyond that, it’s a very loose adaption. All characters besides the aforementioned three (Hunt, Max and Phelps) are either missing, swapped around in their roles or have significantly shortened screen time. Phelps’ wife Claire most notably is replaced as the female sideckick / potential love interest by the much more boring Candice Parker, a captured agent whom Hunt has to rescue from the clutches of the KGB in Prague.

That insignificant little plot point of everyone dying in Prague is also gone, robbing the following witch hunt after Ethan of all plausibility. More care was taken in implementing the movie’s trademark gadgets, namely the face maker and the explosive gum, although they’re used in new situations. The trademark phrase in the briefings is also changed from the movie and is actually more in line with what one would hear in the classic TV series (“decide” instead of “chose”).

The gum is in the game, the guy isn’t.

Most of the game’s “stealth elements” consist of the gimmicky use of such… gimmicks. The objectives usually break down to “find your gear, use gear a at location x and gear b at location y, shoot a few people, find the exit.” Staying undetected usually means getting a new face in order to be able to walk around freely. There’s a button for crouching down, but it doesn’t seem to be of any use. Sometimes it can be advantageous to attack enemies from behind, and at one point Ethan can spray blue paint on surveillance cameras to avoid more guards getting after him. But generally the game is just alternating between item combination puzzles and shooting segments. The “puzzles” are never very challenging, though. Most of the time you’re straight out told where to go and what to do there. Only sometimes targets don’t show up on the radar, leading to the 3D equivalent of a pixel hunt, like when Ethan has to find the switch that opens the door to a secret communications room in an office.

Typical for the period, the camera moves around awkwardly. The only form of control allows switching to a very close over-the-shoulder view, which also makes Ethan transparent. With a weapon drawn, this automatically triggers manual aiming mode, which works similar to Rare’s N64 first person shooters, but unlike James Bond or Joanna Dark, Ethan can slowly strafe while aiming. Just shooting while running is usually accurate enough, though, as long as agent Hunt is facing in the right general direction of the enemy and no ally is standing in between.

Occasionally the game breaks out of the standard formula for special tasks. The key scene where Ethan slides down on a rope to infiltrate a high security server room simply couldn’t be left out. In another mission, the player takes control of another agent from a sniper position to protect Hunt, who is running around aimlessly at the station while ordinary people and trained assailants alike keep acting overly suspiciously around him. The last scene finally puts Ethan in control of the cannon on a gunboat and is just one big orgy of destruction.

In 1998, this was a cool effect.

All the different sequences share the same awkwardness of controls: The main game frequently switches between tank controls and “normal” directions, and it’s hard to discern whether or not you’ve taken down an enemy until he collapses with noticeable delay. The rope in the server room relies on unintuitive yanking of the analog stick to make Ethan swing around, and the station level has dead angles that can’t be seen from either of the two available sniper positions.

Apparently the designers tried to compensate by making the game rather forgiving of mistakes. Ethan has a ridiculously long health bar, and although its status is carried over throughout all of the up to eight parts of a mission, it’s fully restored after losing once or restarting the segment. There are some annoying parts, mostly concerning lasers or electric fields, but overall the game is rather easy – at least in “Possible” mode. On “Impossible” Ethan is a lot easier to kill and the enemies are more aggressive at the same time. It also adds a few extra objectives here and there, though never quite as extensively as “00 Agent” in Goldeneye did.

Although Mission: Impossible was originally supposed to be a Nintendo 64 exclusive title, Infogrames followed up with a PlayStation release (developed by X-Ample Architectures) a little more than a year later. Far from being a lazy downgraded port, it made full use of the advantages of the CD format, or at least tried to do so. The briefing scenes are replaced by FMVs, which manage to look not even a tiny bit more detailed than the former in-game ones while being plagued by horribly fragmented compressions. The port does add a few new effects like better lighting and working mirrors. Ironically, early N64 preview screenshots showed off the latter, producing hilarious (in hindsight) captions like “mirrors are no problem for the power of the N64!” in magazines. Texture quality, on the other hand, takes a nosedive on the 32-bit console, and the interior drawing distance is much shorter, covering the far ends of long corridors in darkness.

It’s even harder than it looks.

Now all the dialog lines are voiced (on the N64, only the two briefing missions are, alongside some silly comments by Hunt whenever he shoots an enemy or gets a new instruction), but the acting ranges from mediocre to horrendous. Worse is that the music just stops whenever a line of dialog is spoken, destroying whatever cinematic atmosphere the bad acting left intact.

Both versions of the famous Mission: Impossible theme, alongside some original tunes, which actually differ between platforms. Both soundtracks fall just a little bit short of excellent, featuring remnants of that distinct Euro chiptune charme, making the interruptions on the PSX even worse.

It cannot be denied that Mission: Impossible is not a very good stealth game. It’s also not a good shooter, nor a good adventure game. Too unprecise are the controls, too trivial the tasks. The two episodes of an unrelated mission in Siberia at the beginning and end feel tacked on, probably because they are. Presumably the long and troubled development didn’t work in the game’s favor here.

Still, Mission: Impossible deserves credit because it was made in a time where a concept of what a 3D stealth action game should be didn’t yet exist. It was released before either Tenchu hit American shores or Metal Gear Solid was even finished, thus constituting the first taste of this new genre for players at least in the West. It’s also not without its moments. In fact, there are a lot of them, be it the quiet exploration of the embassy in Prague with its luscious architecture (by 1998 console game standards), the cool gunfight with Max’ thugs in the train, where Ethan has to take care not to hit any civilians, who even can be taken hostage by the goons, and of course the rope scene. It’s a flawed game full of great setpieces, and those are what make this game worth checking out.

More cheap thrills await in Operation Surma.

This wasn’t the last gamers heard of the Mission: Impossible franchise. Infogrames put out a Game Boy Color game the next year, which was as unrelated to the console offering as it was uninspired. M:I – Operation Surma is often considered a spiritual sequel, since it features Ethan Hunt while not being based on any of the movies. It was published by Atari in their Infogrames-owned incarnation, but developed by an entirely different team at Paradigm Entertainment. (The Pilotwings 64 company’s involvement should explain the screenshot above.)

Sources for pre-release info: Total! (Germany) 6/97 & 5/98; Computer & Video Games 8/97 (#189); Unseen64