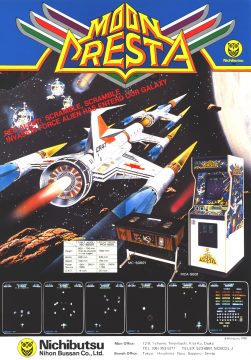

Nichibutsu is a Japanese arcade developer which probably won’t ring too many bells for most classic gamers. A division of Nihon Bussan, an electronics company, its most successful title outside of its native country was Crazy Climber, an obtuse but silly game about scaling buildings. Within Japan, though, they’re well regarded as the creators of Moon Cresta and its successor Terra Cresta, two very well regarded shoot-em-ups from the early age of the genre. There are also a number of spinoff titles, such as UFO Dangar Robo and Armed Formation F, that use similar mechanics despite not technically being part of the series.

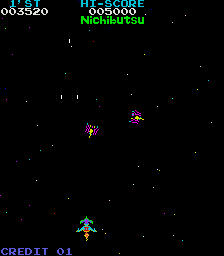

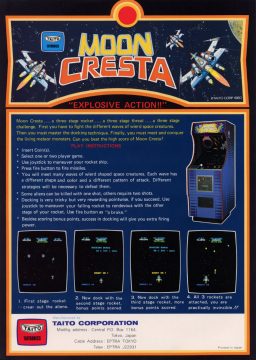

Moon Cresta was one of the first of many single screen shooters from the early 1980s, designed to capitalize on the popularity of Namco’s Galaxian. Moon Cresta runs on the same 8-bit hardware, has the same sparkling star field in the background, and even uses some of the same sound effects, like the whistling of missiles as they leave the player’s ship. However, there are two key differences.

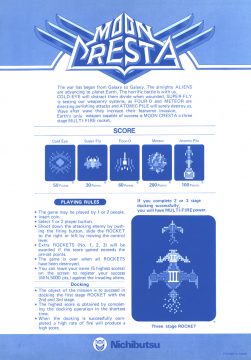

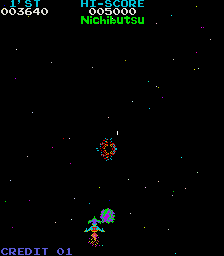

The first is that while there are fewer onscreen enemies, they’re also wilier, flying in confounding elliptical patterns. Your first foes are Cold Eyes, which swirl above you in figure eights before swooping down for the kill. Shooting a Cold Eye splits it into two ships, making it crucial to destroy both halves before aiming for the others to keep the onscreen chaos manageable. After two fleets of Cold Eyes, your next opponents are Super Flies, which are slightly less crafty but more numerous.

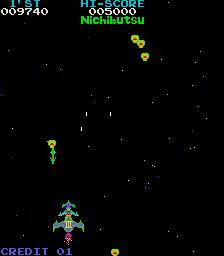

Swatting the two swarms of Super Flies reveals the game’s other key difference from Galaxian. Like most shooters from the early 1980s, you’re given three ships, but they’re three different ships, each more powerful but also larger than the last. If you can survive four rounds, you’ll be given a chance to dock your fighter with one of the remaining ships, in a mini-game similar to Atari’s Lunar Lander. The fire button turns on your thrusters, letting you gently guide your ship down to its ally. A successful dock merges the two ships, boosting your firepower and preparing you for future waves of more dangerous aliens. Crash and you’ll lose one of your ships, leaving you at a disadvantage when the game gets tougher.

It would be easy to dismiss this feature as a knock-off of Galaga‘s dual ships, but keep in mind that Moon Cresta was released one year before Namco’s sequel to Galaxian. Also, all three ships in Moon Cresta can be brought together, creating a tower of death that makes short work of the Four-Ds (AKA Arrow Ships), Meteos, and unfortunately named Atomic Piles that menace the player in future stages. On the down side, the fully assembled Moon Cresta ship is an easy target for the circling swarms of aliens, and once one of the ships in your fleet is gone, it’s gone for good unless you can earn a kingly score of 30,000 points. With enemies worth as little as 30 points each, that may take a while.

Moon Cresta exists in several forms beyond the original arcade release by Nichibutsu. It was rechristened Eagle and given new graphics by Centuri, famous for distributing many of Konami’s early arcade games in the United States. There was also a revised version of the game by Sega/Gremlin called Super Moon Cresta, where the already tricky enemies dropped missiles of their own. Finally, there was Moon Quasar, a semi-sequel which challenged the player to dock with a brightly colored mothership between stages for bonus points.

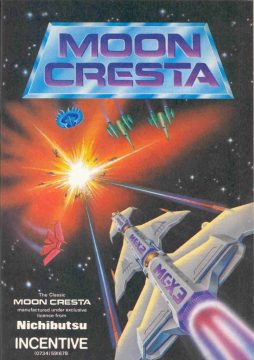

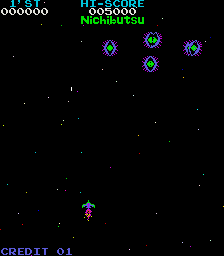

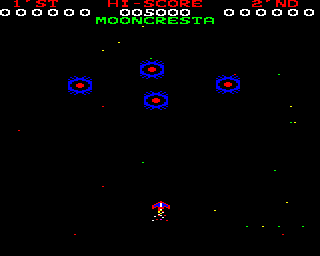

Moon Cresta never saw much action on the game consoles of the early 1980s, but it was ported to a half dozen home computers courtesy of a small British publisher called Incentive. According to the World of Spectrum web site, Incentive founder Ian Andrew paid 1000 pounds (roughly $1500 dollars) for the license, and was given free rein to publish Moon Cresta for any computer he chose. Those included the Commodore 64, BBC Micro, ZX Spectrum, Amstrad CPC, and Dragon 32, a close cousin of America’s TRS-80 Color Computer. Most of these ports are solid conversions, with several adding impressive particle effects that fill the screen when the player’s ship explodes. Moon Cresta on the Dragon 32 is presented entirely in black and white, while the other games have more colorful, yet chunkier graphics. Amusingly, many of these conversions include an illustrated options screen with a ten pence coin slot next to the key that starts the game!

On the Japanese side, there is an official port for the PC-8001 computer, as well as an unofficial conversion under the name Moon Alien, which has extremely large, chunky visuals.

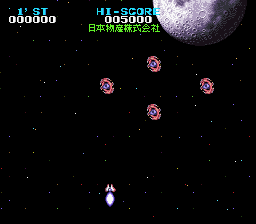

Years later, Moon Cresta surfaced as part of a collection for Japan’s Sharp X68000, published by Dempa/Micomsoft, and in Nichibutsu Arcade Classics for the Super Famicom and PlayStation. The X68000 version is bundled on the same disk as Terra Cresta, and you need to hold down F2 as the system boots to access it. This port is just about arcade perfect. The SFC and PS1 ports have graphics straight from the arcade game and look decent on the outside, but have alterations to the enemy speed and other characteristics, which makes them unfavorable to fan of the arcade game. The PS1 compilation also includes a game called SF-X (Space Fighter X), which is yet another variation of Moon Cresta with different, more detailed graphics and denser enemy patterns. What’s strange is that it’s completely different from the SF-X arcade game Nichibutsu released in the arcades in 1983. This was a side-scrolling shooter, and was known outside of Japan as Skelagon.

Moon Cresta was released on its own for the PlayStation 2 as Oretachi Game Center Zoku: Moon Cresta, with Terra Cresta being sold on a separate disc. Most recently, Moon Cresta surfaced on the Android operating system courtesy of the game’s new IP holder Hamster Corporation, and was ported to the Atari 7800 by hobbyist programmer Bob DeCrezcendo.