If the Mother series exists, it’s probably by chance. As early as 1987, Itoi already had a video game project in mind, but he had no idea to whom he could propose it to. One day, he received a phone call from Nintendo on a totally unrelated note, the ad campaign for the 1987 Famicom Disk System dating sim Miho Nakayama no Tokimeki High School, and that’s when he took the chance and mentioned this little project of his. And the Kyoto giant actually seemed interested enough. Not long after that call, Itoi had an interview with none other than Shigeru Miyamoto to convince the company about the project…and actually failed to do so. Indeed, Mario’s famed creator wasn’t all that convinced by what he perceived as yet another celebrity that just wanted to make a game for the sake of it. Itoi is said to have cried on his way home. However, Hiroshi Yamauchi, who was still the company’s CEO at the time, had a different opinion – he thought video games lacked innovation in the recent years, and someone he considered as a genius like Itoi was the perfect fit for the situation. This lead to a second phone call, given by Miyamoto himself, to notify Itoi that the project had been greenlit.

This is when the APE Inc. studio was founded. It would soon be joined by other external figures, such as visual artist Minami Shinbo, who worked as a character designer. Itoi was pretty serious about the soundtrack too, and two composers were brought in: Hirokazu Tanaka, a senior Nintendo composer who worked on the company’s earliest arcade titles as well as on cult classics like Metroid or Tetris; and Keiichi Suzuki, a friend of Itoi’s and the leader of an alternative rock band called Moonriders. Pax Softnica, a subcontracting company that had already worked for Nintendo on games such as Shin Onigashima, was tasked with programming the game. Itoi chose the “Mother” title for two reasons: First, in reference to the John Lennon song of the same name that made him cry the first time he heard it; second, to use a title that wasn’t “video game-like” and distinct from all these “Quests”, “Legends” and “Stories”. Development started in 1988 and, apart from long daily train travels for Itoi and some issues with the game’s balance, things went pretty smoothly. The game was completed around one year later.

Miyuki Kure (game designer), Keiichi Suzuki (composer) and Minami Shinbo (character designer).

In the early 1900s, a dark shadow fell over a rural town in America. Shortly after, a married couple mysteriously vanished. The man’s name was George, and the woman’s name was Maria. Two years later, George returned home but never told anyone where he had been or what he had done. Instead, he deeply immersed himself in strange research. As for his wife, Maria…she never returned. We then switch to the year 1988, in the house of a young boy called Ninten on the outskirts of the town of Mother’s Day, where a poltergeist suddenly starts wreaking havoc.

Characters

Ninten – にんてん

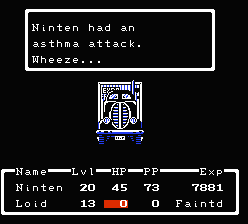

The 12 year-old hero from the town of Mother’s Day, and George’s great-grandson. He’s your average American boy, except he so happens to be gifted with PSI powers. His father is absent through the whole game, and he also has asthma.

Lloyd / Loid – ロイド

The grey-haired nerd from the town of Thanksgiving. Unsurprisingly, he’s constantly being bullied by his schoolmates, and is often found hiding in a trash can. He doesn’t have any PSI powers, but he’s a genius who can operate artillery and even tanks at the age of 11.

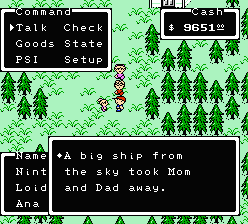

Ana / Anna – アナ

The daughter of the pastor from the town of Snowman. Her mother has been abducted, and after meeting Ninten, as she had foreseen in a dream, she joins him to find about her mother’s whereabouts. She’s physically weak, but she has very strong PSI powers.

This very short prologue is what the Mother series opens on. Most RPG enthusiasts back then had grown up with the likes of Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest, so just try to imagine the look on their face at the sight of such an introduction. The first Mother game may not be perfect, but he has one indisputable merit – that of laying the ground for a transgression of the universe of role playing game.

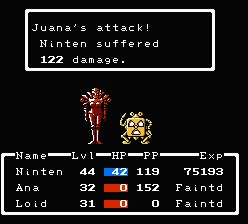

However, in all honesty, we’d probably better start with what’s wrong with the game. Especially to this day. Let’s sum up Mother‘s gameplay: it’s a classical JRPG where you’re tasked with finding eight melodies across the world, after which you get to face the final boss. Of course, you’ll have to deal with turn-based, first-person random battles during which you can perform the usual actions – attacking, guarding, using items or a variety of offensive and defensive skills. If your whole team is knocked out, it’s game over, and you’ll be sent back to the last save point without losing any data. And… that’s it, really. You really don’t need to know anything more when it comes to Mother‘s core gameplay.

And it didn’t age well. At all. Actually, it was probably already archaic at the time of its release. Because, yeah, it’s a Dragon Quest clone, pure and simple. Gameplay-wise, it’s completely rusted, and the addition of an “auto” battle mode isn’t gonna change that. On top of it all, the balance is terrible – enemies are just hardcore to the bone and battles subsequently feels extremely unfair, the encounter rate is borderline crazy, and healing will require never-ending round trips. In short, you better get used to grinding and dying, because you’re gonna do a LOT of both. The game can get so irritating that a fan patch was created to double received experience points. And knowing Itoi himself openly admits they were like “whatever” when it came to balancing the last area of the game, which is indeed the very incarnation of insanity, it’s not really a crime to use it. Whatever choice you make though, just know that you’re gonna die. Unexpectedly and often.

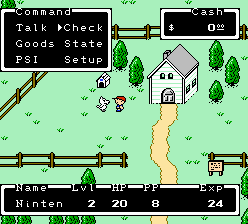

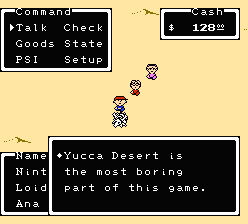

Does this mean Mother‘s game design is unplayable? Not really. After all, a very interesting concept was introduced in this game – the continuous, uninterrupted field. Instead of being divided into a world map and town sections, the whole game is just like a vast area where everything is connected without any need for transition,. And all of this through the lens of a slightly tilted, isometric perspective. This does have a downside, though – the landscape is so repetitive it can be easy to get lost, and you don’t want that to happen with bloodthirsty monsters lurking at every corners. That was the price to pay to get the chance to walk around this new land, whose “hugeness” and feeling of freedom left players feeling impressed.

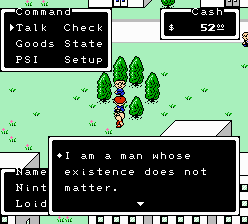

Another peculiar aspect is the unsettling lack of narration throughout the adventure, which is exclusive to the first episode of the series. Indeed, Mother has a very short prologue and a whole bunch of important events crammed up at the very end of the story, but… almost nothing in between. You’re basically thrown in your journey and you’ll have to deal with it on your own. Add that minimalism to the gigantic game field, and it really creates a weird atmosphere – it’s like the game is saying, “save the world pretty please!”

The progression is non-linear, so much that there are chances you might actually miss something out and have to come for it back later. If you go too far in the game’s world, overpowered enemies will punish you for it anyway. In the end, it’s kind of a good thing actually, and this pervading feeling of uncertainty has its part in that first Mother game’s atmosphere. That doesn’t mean the game’s universe is just empty, though. It does have one aspect that’s a whole lot different from the others – its setting.

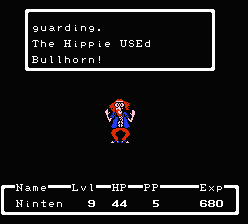

Mother may not be the very first RPG to take place in a modern setting, but it most certainly is the first one not only to try to recreate the whole of society in its universe, but also to decide to look at it through the deformed lens of parody and absurdity. Welcome to America as seen by Shigesato Itoi! Screw swords, dragons and kings – here you’re fighting hippies with baseball bats while on a quest for the local corrupt politician. Everything has changed from the usual RPG standards – towns, institutions, characters, enemies, events, items, everything. Even your money – it’s now sent on your bank account by your dad, and you have to withdraw it at an ATM. Supernatural occurrences rely on cartoonized popular culture, such as zombie and alien invasions or your skills being “psychokinetic” powers. From the essential to the anecdotal, everything in Mother is modern in its own strange way. Playing this game is like living in a world we all deeply know, even though it’s just too exaggerated to be taken seriously.

An almost-absent narration in a brand new world – that must be quite an odd premise for the player to follow. However, in some ways, the game manages to be somewhat touching. Itoi wanted to create a game that could transmit simple emotions to both children and adults alike. The game is almost entirely void of what is traditionally considered “epic” events, most probably because it actively sought to avoid doing so. The journey through this somewhat-familiar land has a sweet taste of innocence embodied not in cliched childish imagery but in a simple display of small token of happiness, such as the childlike thrill of a first airplane flight. Mother‘s world is not one of quests of glory against evil – there is no holy hero and no bad guy to vanquish. Those wouldn’t even fit in the game as caricatures. Even the game’s antagonist is completely different from what you would expect from a “final boss”. It has become pretty obvious by now that the game has truly started something unique.

“In the very middle of the spectrum, you have fun and games. Beyond that, you’ve got mean pranks, and crimes. And beyond those crimes, you have evil. And on the opposite side, you’ve got the very embodiment of justice. But to me, evil and the embodiment of justice are both unpleasant.” – Shigesato Itoi

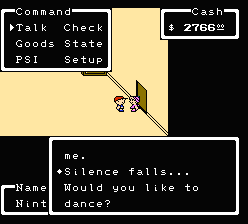

It really was a great idea to deviate from the usual RPG tropes. Thinking back to the usual medieval NPCs, they were pretty ridiculous. While those of Mother are… well even more ridiculous, actually. But this time, they are on purpose. Humor is a very important part of this game that would set the tone for the whole of the series. Of course, Final Fantasymanaged to tell a joke or two, but what makes Mother so different in this aspect is how its wackiness doesn’t lie in occasional puns but is an integral part of the game’s universe. It simply goes in pair with its originality – it’s inseparable from its imagination. But this wackiness goes deeper – deep down, in fact, to the game design itself. It may sound strange, but the world of Mother isn’t just a world of quirky NPCs – it also is a world of morally ambiguous bats and insensitive physicians. Of inopportune flu pandemics and talking trash cans. Of fleas and rulers.

What a surprise indeed when the opposing bat, which you were preparing to knock out, decides to just waste its turn “thinking about the circumstances”. And these unexpected twists only gets more convincing as they appear in the battle interface as would have regular damage prompts or status changes! That attitude of presenting completely screw-loose occurrences as something natural is truly a force that would define one of the series’ most peculiar aspect. It only gets weirder with the doctor – if you refuse to pay the astronomic fees he demands, which so happen to be equal to the entirety of your purse, he’ll just tell you to leave and die on your own. It’s part of the game design, but it doesn’t have a clear purpose other than make you laugh or feel awkward, or both when possible. This may seem like a very odd analysis of the game’s content, but more than just break away from the RPG mass of the time, it also created the launch pad which EarthBound would use to take off and break away from everything.

“A game isn’t something that can be made by one person alone. Well, it’s possible that a really hard-working game creator could finish a game all alone, but even then he would still need a player. Games grow and mature when they’re created, played, and conveyed over and over.” – Shigesato Itoi

To give this unique world a final touch, it needed a soundtrack in accordance with its awesome setting. And it couldn’t have been more fitting than this. Remember that the composers aren’t small timers – Suzuki was already part of an alternative rock band, and Tanaka was pretty well known for his work with Nintendo. Pushing the Famicom to its ultimate limits, the two composers produced a soundtrack that was worthy of their experience. Suzuki is the one who gave the game’s music a definitely pop-rock direction, thanks to excellent Beach Boys-styled percussion but also to a very Beatles-influenced overall feel. He was also behind most of the more chamber-sounding tracks, as well as the iconic Eight Melodies, a very simple yet powerful piano melody that deserved its place as the game’s central element. But Tanaka isn’t just here for show, and his interest in electronic music drove him to write more haunting tracks, powered by what probably are among the best bass lines of the Famicom, in addition to more pop tunes. Both artists were aware of the technical limitations of the 8-bit hardware, and they were cautious in creating a stripped-down yet rich sound in part by taking inspiration from how some new wave or prog rock groups managed to create something new with limited means. There’s no denying it: the game’s rock’n’roll feel only makes it stands even more apart from the crowd, far away from wannabe pompous orchestras. These chiptune riffs are indeed the icing on the cake that established the first Mother game as a truly alternative work.

“I wanted to get a feeling similar to that of Godley & Creme’s Lost Weekend across in Mother. It was an incredible idea to recreate the sound of an orchestra by rubbing the strings of an electric guitar, but it was a sound that was actually quite close to what the resources were for in-game music at the time.” – Keiichi Suzuki

This is the kind of gaming experience you’ll get from playing that strange gem. Mother really is truly unique. In all honesty, it can be tough to bear those gameplay hassles, especially today. But if you can get through that trouble, and you really should, you’ll get to grasp how this game simply is something else: the atmosphere, the humor, the experimentation, the soundtrack! Mother should not only be remembered as a great game, but also as the lab in which the genius of EarthBound started to form.

“No crying until the ending.”

(Ending made na kun ja nai.)

Mother was finally released on July 27, 1989. The reception was ground-breaking – in the end, the game sold more than 400,000 copies and reviews unanimously lauded the game’s uniqueness. Mother often ranks pretty high in most Japanese Famicom- or Nintendo-themed polls ever since, when it doesn’t just make its way in “best games ever” top lists. Entire generations will forever remember their experience with this game – and yes, that’s “generations” in plural, since adults played it too! This definitely was a perfect introduction into the realm of game design for Shigesato Itoi. Seeing the game’s success, Nintendo was initially interested by the idea of marketing it outside of Japan even though nobody knew about Itoi in the US. A translation team was promptly created and, one year later, the localization of Mother as Earth Bound was already completed. The only step left was to release it… and it didn’t happen. Unfortunately, the upcoming release of the SNES made Nintendo hesitant about its hasty decision, and the release of the game was initially delayed but then implicitly cancelled.

In the end, Westerners never got to play the game at the time of its release. It would take a few years, but a prototype cartridge of this forgotten localization finally surfaced in online auctions around 1998 and it was bought up by the now famous Demiforce hackers group after a financing campaign. The dumped ROM quickly spread over the Internet, of course. Phil Sandhop, who was responsible for the localization’s script, certified the circulating version as legit. The game was also unofficially renamed to “Earth Bound Zero” in order to avoid confusion with the actual EarthBound that was released during that time lapse. Nintendo eventually later released the game on the Wii Virtual Console, listing the name in the menu as “EarthBound Beginnings“, but the title screen game is unaltered, and the actual game is identical to the leaked ROM.

There are numerous small changes to enemy graphics as forms of censorship – the smoking crows no longer have cigarettes, and the zombies no longer have bits of blood on them. Crosses have been removed. The dungeon design in Magicant is also slightly simplified. But there is a fairly extended ending, compared to the rather brief finale in the Japanese version. The “PK” abilities are also renamed “PSY”, which carries over into the localization of the SNES EarthBound. This accounts for why Lucas yells out things like “PK Fire!” in Super Smash Bros. Brawl, since they left the voices for the character in Japanese, using the Japanese term. There is also a run button, which is quite handy given the slow walking speed.

In 2003, Nintendo released Mother 1 + 2 for the Game Boy Advance, a compilation of both games for the portable platform, only in Japan of course. Graphically, this version looks identical to the Famicom version, though since the resolution is smaller, parts of the screen had to be chopped off. The music also doesn’t quite sound the same, either – it’s not terrible but some instruments, particularly the drum samples, sound off. Weirdly, this version is actually based off the unreleased NES version, so it has the censored enemies, run button, changed dungeon designs, and longer ending.

Screenshot Comparisons