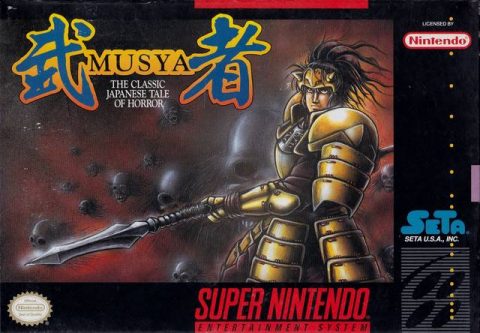

Musya: The Classic Japanese Tale of Horror reached the US in 1992 via the Seta Corporation. Its developer, Jorudan, made the classic Crazy Climber for Nichibutsu in 1980, and an Aliens vs. Predator beat-em up for the SNES in 1993 (unrelated Capcom’s own take on the franchise), but was mostly responsible for porting other company’s arcade games to home consoles along with their Hisshou 777 Fighter pachinko series. While Musya looks like a rushed grasp for original notoriety, Jorudan’s successful execution of yokai designs would make for a big payoff years later with their creation of the excellent ParanoiaScape for Joji “Screaming Mad George” Tani.

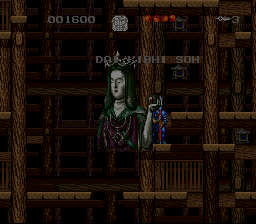

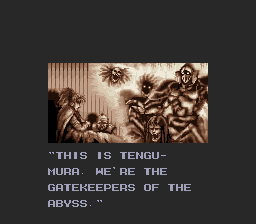

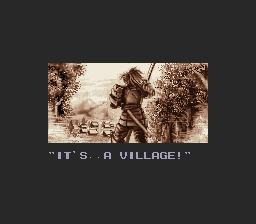

Our story begins with Imoto (or Jinrai in the Japanese release) wandering aimlessly from a battle of which he is the lone survivor. Wounded, he stumbles and collapses into a nearby village, only to be rudely awoken by the mayor. He’s informed that the unassuming people of the hamlet, Tengai-mura, are in fact responsible for keeping a demonic lair sealed and that his daughter, Shizuka, has been kidnapped and locked up deep within the abyss. Without her, the gateway between the demon world will open up, so Imoto immediately strolls into the gateway to hell with nothing but his trusty spear.

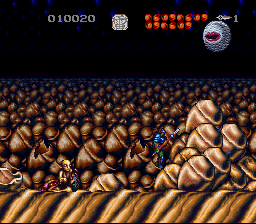

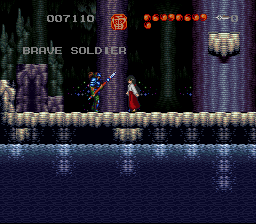

There aren’t many side scrolling games out there where the protagonist’s main weapon is a pike, and it could make for some interesting techniques and situations. Unfortunately this is not realized at all in Musya. Here, Imoto can stab forward, or hit a button to spin his pike around him to deflect projectiles and do minimal damage to enemies. He can also do a downward stab while in midair. Curiously, the SNES’ triggers are used to perform what I can only describe as an advanced cower in fear technique unique to this game. Holding one of the triggers will make Imoto crouch and slowly move backwards, holding his spear out in front of him. This confers no benefit, nor are there any extra moves you can perform while creeping backwards, so it’s pretty impressive in its uselessness. You also earn magical spells as you progress. These are similar to the ninjitsu in the Shinobi games, damaging every enemy, healing you a little, etc. You can also find power ups that will evoke a specific deity to help you out, though their effects aren’t particularly impressive.

Most importantly, you can hold up on the control pad while jumping to jump absurdly high. Due to how the platforms and hit detection work in the game, you’ll basically want to hold up every time you jump. It would have been better to imitate many previous platformers where one can jump higher just by holding down the jump button itself instead of having to press up also since you’ll be doing this for entire game. Imoto walks very slowly, and most enemies are fast and require multiple hits to kill. Brilliantly, they also reappear almost constantly. In later levels you can use a screen clearing magic spell and many enemies will already be back by the time it’s done. They pop in from specific points in each level, just appearing out of nowhere. Most of the game is ideally navigated by using that high jump to avoid as many enemies as possible. It is possible to fight through everything you encounter, but it’s such an unenjoyable process as to not be worth it. There are of course numerous power ups that will improve the strength and range of your spear, but like in the original Darius, it takes so many to make a difference, and you lose all of it every time you lose a life, so unless you have the game fully memorized they are useless.

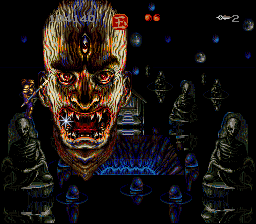

Each level culminates in an encounter where Imoto duels with a powerful supernatural entity. At the end of the first level as an example, Shizuka appears ready to be rescued, but it turns out to be a giant tanuki in disguise. Even worse, one of the more dramatic boss fights can result in you becoming stuck and having to restart the game. For most of the bosses, you enter a new area where the boss dialogue and confrontation happens. For the boss of level seven, however, since you have to pass through a short level with some enemies before him, it’s possible to jump over the trigger that awakens the boss, leaving to you wander around a short, empty level endlessly until you reset the game.

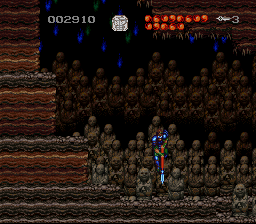

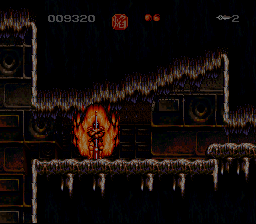

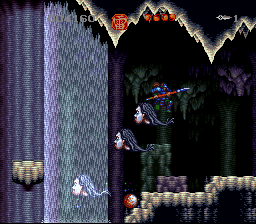

The level design is a bit of a mess too. Some levels feel fairly open and let you explore a little bit, and have a few different paths to the end as a result. Others are pretty much a straight line, and one even penalizes you for exploring by warping you back to the beginning if you take a wrong path! The final level is particularly torturous. For most of it every platform is a narrow precipice combined with an unending hoard of fast flying foes firing metal spikes at you. All of this is set to a very unimpressive soundtrack that does little to evoke the “classic Japanese Tale of Horror” the game’s box claims itself to contain. It’s a surprising disappointment, as one of the composers, Tenpai Sato, would go on to do very successful music compositions for games like Valis II (PC Engine), Soul Nomad, and the Disgaeaseries.

In a hilarious twist, you actually return Shizuka from the abyss halfway through the game, before venturing back into its depths. After the dialogue finishes, this is represented by having to replay some of the levels. The awful part is that of the game’s eight areas, only five of them are actually unique. Two of these repeats have new bosses, but the strategies for beating them are barely different from the originals and do nothing to make up for the laziness of having to play through the same three levels twice over. Insultingly, the levels all have different names even though the repeated ones are identical to each other in every way save the bosses.

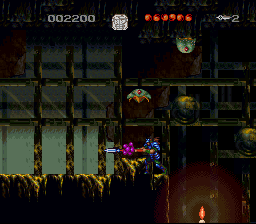

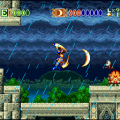

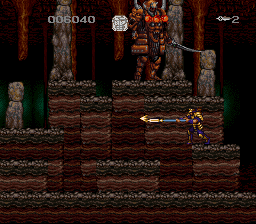

Musya‘s graphics do not alleviate this either, as, while the enemy designs are good, all of the sprites are extremely small, with minimal animation. There’s also a lot of slowdown, as the game often employs a dithered “transparent” fog effect that is barely visible, only making the game more tedious instead of adding to its attempted foreboding atmosphere. The effects for the spells are extremely plain also, failing to have any real sense of impact (especially when the ones that damage enemies result in new enemies almost immediately reappearing anyway). Interestingly, one of the graphic designers, Takanori Wada, must have taken a liking to small monster designs, as he went on to do graphic design for several Pokemon games in the early 2000s.

The worst thing about Musya‘s graphics, however, is that the backgrounds are great. All of them are very evocative of the game’s yokai horror stylings, with very shadowy lighting and some macabre details somewhat comparable to other cult classics like Otogi: Myth of Demons (Xbox, 2003) and Samurai Ghost (PC Engine, 1992). The backgrounds feel like they belong in a much more polished game compared to the tiny, poorly animated sprites and grating soundtrack. Musya is the kind of game that had some talent and good ideas behind it, but is so much less than the sum of its parts.