For a minority of video game players, the Saturn is fondly remembered as a console with a handful of outstanding games that, possibly because of new and emerging industry tendencies in the mid and late nineties, were never granted the proper acknowledgement. From the domestic conversions of Sega’s greatest arcade hits to the exclusive titles that the company and a few third-party studios somehow managed to produce, this was a system with known hardware issues and an ever shrinking market scope.

The last years have been particularly important in the process of unveiling the broader truth: the Saturn’s short life was, in fact, very eloquently lived by means of several games, most of them Japanese exclusive titles that are now held as myths and sporadically sold as expensive relics of a not so distant past. And while an increasing number of game collectors keep tracking down some of these lustrous pearls, the rare items that are sold in auctions and import stores for exorbitant amounts, there is also a great deal of value to be found elsewhere.

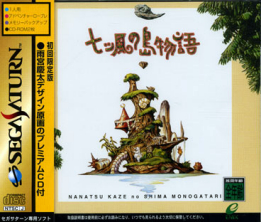

Nanatsu Kaze no Shima Monogatari, roughly translated by the developer as “The Seven Blasts of Wind in Island Story” (but better translated as “The Tale of Seven Winds Island”), is a commonly neglected masterpiece released by Enix exclusively for the Saturn in 1997: one that didn’t obtain the same accolades as other RPG and Adventure titles released for this system. As a two CD set, the game was accompanied by a Premium disk that featured some of the most beautiful matte art ever conceived for a video game, along with singular item and character designs. Essentially, Nanatsu Kaze no Shima Monogatari is an interactive storybook whose illustrated chapters reflect the game’s very own narrative, with a new chapter being added every time the player successfully completes a group of tasks.

In a rock floating over the skies stands a large and spiked egg beside a black feather, the hundred year old heritage left behind by an ancient lineage of creatures from the Seven Wind Island. The character inside it, Garpu, is a predominantly green, biped dragon that coyly cracks the egg crust only to find that he is trapped on an isolated piece of rock high up above. Hanging on to the feather and raising it with confidence, the quirky Garpu is unexpectedly pushed off the rock by a black current of wind, then falling over the ground of a strange island below him. As he recovers from the fall, a mysterious seed jumps in his direction and hides in his pouch. After being planted, the seed sprouts instantaneously, thus assuming the form of a great tree house.

Inside it is a valuable book that provides information about all the bewildering creatures that inhabit the island. Their names, descriptions and pictures are sorted by different categories according to their class. Fulfilling his destiny, the improbable hero Garpu will make himself acquainted with all of them, from the wise giant snail Soul, who provides poetic and ambiguous clues, the roaring Wind Lion, with a children’s windmill strapped to his tail, or even Tamu, the gigantic pipe smoking trader who sleeps in the heart of the forest.

By interacting and trading information with his fellow characters, Gaapu will learn about harnessing the legendary seven winds and the method to use them in his favor, overcoming the obstacles that appear with each new challenge. Other characters, however, will join and accompany him during the quest, appearing on the screen when summoned by a sea conch: their unique abilities will allow the protagonist to broaden his horizons, exploring otherwise unreachable locations of the mystical islet.

Those who were fortunate enough to play Enix’s Wonder Project J games for the Super Nintendo and Nintendo 64 are bound to notice some resemblances in the peculiar style of character drawing and the taste for exceptional animations: in no way a coincidence, since one of the several small studios gathered to create this project was none other than Givro, the creators of the above-mentioned Super Nintendo masterwork. But while Wonder Project J is fundamentally a blend of point-and-click adventure with raising simulation and a little hint of Bishoujo, in Nanatsu Kaze no Shima Monogatari the player takes full control of the character’s actions – very much like a slow-paced platform game.

Another important component of this title has to do with the recollection of insects, plants and fish, which can be used either as key-items for trades, causing the narrative to progress, or solely for Gaapu’s private collection, kept in a dedicated space inside the tree-house. Each of these activities can be performed only with the use of dedicated items: for instance, to capture bugs, Gaapu needs to use an extendable claw (similar to Yokoi’s Ultra Hand, by the way). When used with the correct timing, it will grab the creatures and automatically store them in the purse he carries around his chest.

The first and long lasting impression originating from this precious Enix release lies in the superior quality of the visuals: incontestably one of best examples of how to employ 2D graphics in a videogame, not only because of the outstanding conceptual art and character design, but also due to the continuous indications of the creator’s talent and admiration for the work itself. Each new part of the island was meant to be admired much like every new painting in a gallery of rare canvases. The exquisite landscapes present carefully selected color palettes combined with animated backgrounds, precisely the sort of visual splendor that was unseen, and I dare say unmatched in that year of 1997.

To crown an already majestic achievement, Givro, Crowd and the other parties responsible for the creation of the game invested heavily on the quality and expressiveness of the animated characters, from the odd protagonist and his maladroit body movements to the massive, fully animated sprites that every so often exceed the threshold of the screen. Artistically and technically impressive, Nanatsu Kaze no Shima Monogatari is easily one of the truest, most blatant examples of the often mentioned “superiority” of the Saturn system in rendering and (mostly) animating detailed 2D visuals.

What graceful dissimilarity, the audiovisual chapter comes to an end with a remarkably subtle soundtrack composed by Buddy Zoo: the austerity that is discernable in some of the most enticing themes (Garpu’s Dream, The Itenerant Merchant) contrasts with the elaborate musical performance recorded in other tracks (In The Large House). Albeit rich, the greater part of this musical score consists of reprises of the main theme, reinterpreted with different rhythm and instruments according to the different parts of the tale. Also quite distinctive, the sound effects manage to couple perfectly with each visual display, illustrating the noise of rustling leaves and the tiny insects that inhabit them, the whisper of raging winds across the suspended bridges, not to mention the unique sounds produced by each communicating creature.

Being an uncommon adventure title, founded on simple purposes such as observing the environment, carefully interpreting the succinct dialogues and make the most opportune use of collected items, Nanatsu Kaze no Shima Monogatari provides a highly rewarding experience that largely benefits from the imagination of its designers: the characters and atmosphere are concurrently appealing and repulsive, in a way that only the great masters of the Japanese school of illustration and animation are able to achieve – see Studio Ghibli, for instance, whose work is among the most evident sources of inspiration for the artists behind this game. A distinctive feeling of other-worldliness is omnipresent in this idyllic scenario about ancient cults, wisdom and the hidden powers of nature. Few, however, will be able to discern its subtleties – in small part because the original Japanese text was never translated, thus making the game quite impossible to be played by those not familiarized with the Katakana and Kanji alphabets.

In short, the Enix game is much like a hidden pearl in an ocean of long forgotten video games. One can’t help but to wonder why a game of refined quality such as this has fallen deep into obscurity, merely commemorated in scarce and brief references on the corner of magazine or website pages. Those who spend part of their days searching for the precious gems whose light has been dimmed by the passing of time are bound to recognize the superlative quality of this production. At the time of its release, the game’s charms were soon extinguished, much like the brief and ephemeral gusts of wind it attempts to portray: but it stands, in effect, as one of the few neglected titles in history that a true video game player can proudly vouch for.