To understand Midway’s drug-busting arcade game NARC, you first need some background of American politics of the era. While the so-called “war on drugs” technically began under Richard Nixon in the 1970s, it was really the Reagan administration that began to crack down on narcotics distribution. They drastically increased the budget allocated to agencies like the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), and implemented harsher penalties for drug possession and distribution. One of the efforts to educate the children of America was called DARE (“Drug Abuse Resistance Education”), which was typically taught in school. But they expanded into other areas where youth tended to congregate, and what other place in the 1980s did the kids love more than arcades? And so, many arcade games were plastered with extra screens with the slogan “Winner’s Don’t Do Drugs”, endorsed by William Sessions, then the head of the FBI.

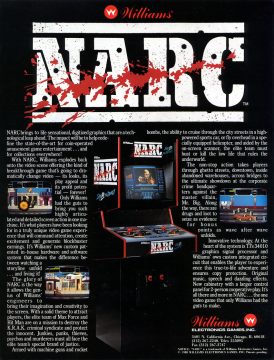

NARC is basically that message, extrapolated into a ridiculous, hyper-violent action game. Midway had previously been known for some kind of silly games like Rampage and Arch Rivals, but this was the first of the new Midway/Williams line that featured these kind of over-the-top themes, which later led to noteable titles like Smash TV, Mortal Kombat, Total Carnage, Revolution X, and others. It was designed by Eugene Jarvis, who previously created Robotron: 2084 and Defender.

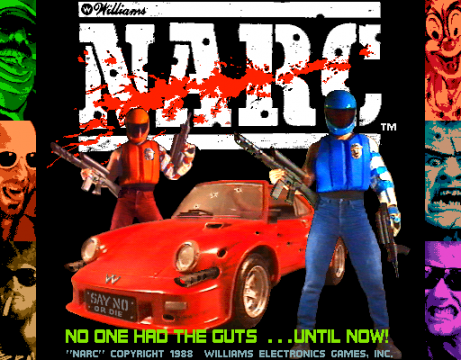

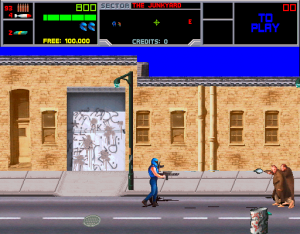

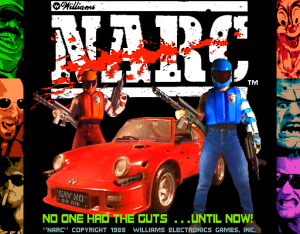

In NARC, you control one of two police officers, each clad in a brightly colored ensemble of a masked motorcycle helmet and bulletproof armor – Max Force (the blue guy) and Hitman (the red guy). Their goal is to infiltrate the headquarters of KRAK, a drug distribution company and terrorist organization, and take down their leader, the mysterious Mr. Big. None of this is done with any subtlety, as the cops are armed with both machine guns and rocket launchers, and a license to murder anyone that comes in their way. The famous “Winner’s Don’t Do Drugs!” slogan is on the machine, though the game has its own catchprase too – “No one had the guts…until now!”

The game is set up like a belt-scroller a la Double Dragon, though it’s set up entirely around projectile weapons rather than melee attacks. There are four buttons on the arcade cabinet, which is liable to cramp your fingers. Two of them are for your weapons, the aforementioned rapid fire machine guns and the single-shot rockets. One of them is to jump, which is really only used when taking on the few mid-air enemies like helicopters, though you can leap away from foes if you find yourself surrounded for a temporary reprieve. The fourth button lets you duck, which is handy for the first stage when the bad guys haven’t figured out how to attack enemies that are crouching, but quickly becomes useless as they learn to shoot low. There are enemies like attack dogs, though, that you need to duck to be able to hit.

Your weapons do have limited ammunition, but most downed enemies will drop some kind of bonus, whether they be more bullets, packs of drugs, cash, or other bonuses that are totaled up as score items at the end of the stage. If you run out of bullets, you can still fire, albeit very slowly; if you run out of rockets, you can’t fire them at all until you pick up more. If you touch an enemy and then wait for a second or two, you’ll arrest them, which sends them flying off the screen and grants some extra bonus points. It’s an incentive to try to enforce the law by efforts beyond mass destruction, though since you need to stay completely still while the arrest is completed, it leaves you somewhat vulnerable to the many, many other foes that flood the screen (you can still attack while the arrest is being done, at least). In a few areas, you’re given the keys to hot Porsche-type sports cars, which lets you run down druggies with ease, though the stages are set up as you can’t drive them for too long without getting blown up by landmines or blocked by other obstacles. Thankfully in these stages there’s usually another one lying just down the road for you for you to drive for a few seconds and then almost immediately wreck. Your tax dollars at work!

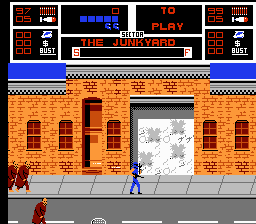

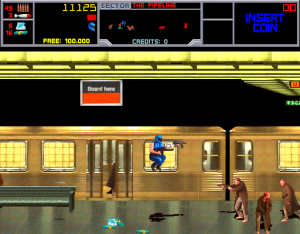

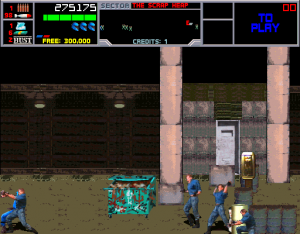

Like some earlier Midway games, the game runs at a higher resolution than other arcade games (512×400), though it also runs on more powerful 32-bit hardware. Its art style consists of digitized images that have been touched up, sort of a prototype of what Mortal Kombat ended up looking like. Each new level is introduced with a close-up of the police scanner, complete with animations, showing the new enemy of the stage, before you get tossed into action. It’s certainly very impressive looking, and sets the stage for the action that almost immediately follows. It’s full of sampled sound effects – beyond the machine gun firing and the explosions, there’s lots of screams and cries from both the cops and the enemies (“You’re busted!”, “Oh no it’s the narcs!”, “Don’t shoot!”). The Game Over theme is a cavalcade of these strung together, as if to show off the sound hardware. The effects largely mask the music, and most of what is actually heard on the arcade cabinet is the deep, chunky bass and the percussion. The second theme level has a cool melody though, and was recognized enough that The Pixies actually did a B-side cover of it, called “Theme from NARC”.

The enemies start off as simple bums from the Das Lof Gang, who hide guns behind their long brown jackets. Dr. Spike Rush (Hypomen) are sunglasses-clad punks that attack by slinging syringes, Joe Rokhed (Dumpster Men) are beefy dudes that are violently strung out on PCP, and Kinky Pinky are mad clowns. The levels take you through every rundown stereotypical seedy neighborhood of 80s urban decay, with backdrops including strip clubs, pawn shops, subways, and other dens of iniquity. One locale is a drug-filled lab with brightly colored chemicals, presumably meth; another is a simple pot farm. A few areas require that you find a keycard in order to advance, just to ensure that you’ve killed the proper enemy or blown up the proper piece of scenery, and rummaged through whatever they left behind. The final level starts off in an upper class city neighborhood before you burst into KRAK’s fancy headquarters and fight Mr. Big himself.

There was very little effort put into the game’s difficulty balance. Each screen floods the screen with bad guys, and it’s intentionally designed to be quarter-munchy. It’s definitely a game that was meant to wow players with its impressive visuals and sordid violence, though it certainly delivers on that end.

NARC absolutely revels in violent excess – the main characters are walking human arsenals, and in theory that’s no different from most other run-and-guns of the era a la Ikari Warriors or Commando, but it’s just presented as so much trashier here, like an exploitation movie. When a rocket makes contact with enemies, they explode in a massive rain of dismembered limbs. The bad guy’s headquarters is called “KRAK”, which is awfully on-the-nose. But the game just hits mega ludicrous status when you encounter Mr. Big. When you first fight him, there’s a portrait on the background of his comically fat face, complete with sunglasses and a cigar, which says “ME” below it in large letters. He slides around the screen in a wheelchair, causing minor havoc as his henchman continue to pour in from all sides.

Once you take him down, you enter his inner sanctum, where he’s revealed to be a gigantic head on top of a tank. And there’s just jowls upon jowls on this guy. Hit it enough and his sunglasses fly off, revealing eyes that shoot out lasers. Destroy that, and it’ll reveal a skull, which unfurls a snake-like neck and continues to attack until you’ve blown that to smithereens. 1980s Hollywood action movies were consistent in portraying druglords as massive scumbags, but what actually is Mr. Big here? An evil robot? An alien? It’s not a question the game feels like it needs to answer. The same basic idea was reused for the Mutoid Man in Smash TV, though there he’s the first level boss rather than appearing at the end of the game. (The final fight of NARC does make a cameo in the 1990 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles movie, as one of the arcade cabinets in the teenager’s hideout.)

The general vibe of the game is just as absurd. You’re technically a police officer, and they are generally supposed to act by some kind of rules, but NARC treats American streets like a warzone, granting the “heroes” license to slaughter more or less anything. (That actually includes innocent prostitutes too, though the canine enemies shrink and run away when you defeat them, because junkie murder is fine but dog murder is not.) Not all of the enemies are technically gang members or drug pushers, as at least one of the enemy class are just drug addicts – even if they’re violent, maybe slaughtering them isn’t the best solution? And the way NARC treats a meth lab as morally equivalent to a pot farm is some top-tier disinformation nonsense.

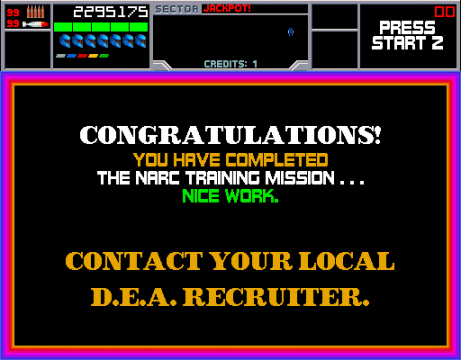

Of course, the question emerges – is NARC propaganda or satire? It’s a hard thing to answer because 80s video games, especially arcade games, are already so inherently over-the-top. But in practice, it can be interpreted as both. Adolescents and teenagers, the primary audience when it was released, are unlikely to be able to observe the satirical elements. (Then again, Paul Verhoeven films like Starship Troopers, an overly violent action movie with deeply anti-fascist themes, still isn’t properly interpreted by many adults, so it’s not like this trait is exclusive to any particular age group.) But when you’ve finally reached the ending and you’re told that the game was just a training mission and to contact your local DEA office for recruitment, it’s hard not to imagine that the guys making it were having a laugh.

NARC was fairly popular in the arcades, and gave way to a handful of ports. None of them quite capture the look, and all of them have control issues. They’re generally easier than the arcade game just because there’s less stuff on the screen, but little effort was made to actually balance the game, beyond just requesting that you try to beat the game on a limited number of credits.

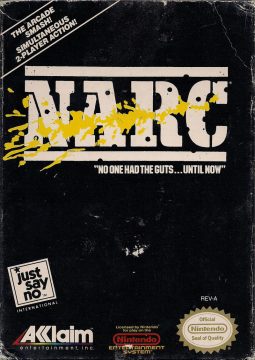

The NES one was converted by Rare, and published by Acclaim. Visually it looks alright, though some of the music tracks have been removed. For the controls, you crouch by holding the B button and jump by tapping it; similarly, hold down the A button to fire the machine gun and tap it to lob rockets. It’s clumsy but it makes sense. If you have a controller that has separate rapid-fire buttons (or map them this way on an emulator), those rapid fire commands are interpreted as a tap, so basically you can set it up to use the same control scheme as the arcade game.

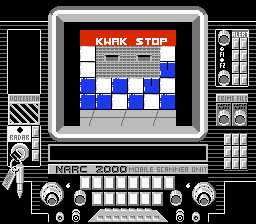

What’s surprising is how much of the game made it past Nintendo’s censors. The blood on the logo on the packaging was changed to yellow (paint?) and removed totally from the title screen, and the bad guys were renamed from KRAK to KWAK, because that particular drug reference was just a little too far. But otherwise it keeps all of the limb-tossing explosions and adult book stores, though it removes the hookers.

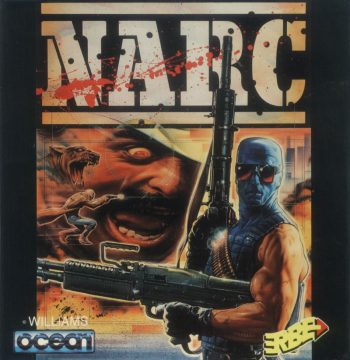

Control-wise, the computer ports come off even worse since there’s only one joystick button for them. The Amiga and Atari ST versions technically look the best, though still not quite to the level of the arcade game. To fire rockets, you need to hold down the fire button for a few seconds, then let go. To jump, you tap up; to duck, you tap down. Frustratingly, the game introduces dogs right at the first level (they normally don’t pop up until the subway area halfway through the stage); since crouching is difficult to pull off, it’s easy to get overwhelmed right out the gate. The scrolling is a little chopper, and generally everything about the controls just feels off. There’s no music, though the sound effects are decent in the Amiga version.

The Commodore 64 version actually plays a bit better. Firing rockets and jumping is handled the same as the Amiga/Atari ST versions, but a separate button on the keyboard (left Shift for player one, Up/Down for player two) is used for ducking. There’s some new music provided by Paul Tonge, too. This is the second-best port behind the NES version. The Amstrad CPC version is the worst. Ugly, blotchy graphics, a small gameplay window, and insufferable speed just make it nearly worthless. The ZX Spectrum version is also pretty slow, though at least looks substantially better in spite of the two-color visuals, but at least it plays relatively well.