Square-Enix’s flagship release of 2010 was Final Fantasy XIII, which almost immediately met with backlash for a streamlined, style-over-substance design philosophy taken to the extreme. On the other end of the 2010 gaming spectrum was Nier, a Cavia-developed, Square-Enix published action-RPG that through a mixture of poor marketing and misguided reviews became one of the overlooked gems of the year.

Nier tells the story of a man in a post-apocalyptic world, where civilization has recovered to an approximately medieval state among the ruins of the old. Humanity survives in isolated pockets seeking safety from mysterious enemies known as the shades – semi-incorporeal, apparently mindless beings that seem to attack humans on sight. Nier has his own struggle in this dangerous world: his young daughter Yonah (or in Japan’s PS3 version, sister – more on this below) is afflicted with a mysterious disease, and he will do anything to save her.

This synopsis may seem simple, but saving Yonah is simply the impetus that pushes you on a winding journey through Nier’s world, uncovering revelations ranging from the personal to the global. The tale is complex but never overwrought, told with a subtlety and uniquely well-developed atmosphere that set it apart.

This atmospheric quality makes Nier the increasingly rare game that lingers in your mind after playing. Part of this is due to the story, which feels almost like something from a bygone era of RPG in its complexity and world-building, yet is carried by the kinds of strong localized writing and voice acting that one might associate with major contemporary RPGs like the Persona series. Aside from the story, many other elements play an essential role in the overall feel of the experience: the gameplay brings in postmodern meta-game elements, shifting genres and paying reference to recognizable titles. The world design creates a strong dreamlike feel, presenting a misty blend of subdued realism with boldly classic “game environments” like the desert city or the machine-themed dungeon. The standout soundtrack further sets the game’s tone, bringing together acoustic instruments and choral runs into a complex sound that runs from gentle to ominous.

Developer Cavia’s name might be familiar from its previous Square-Enix outing, PS2’s Drakengard, which wrapped uniquely warped characterization and story ideas around somewhat flawed action RPG systems and limited visuals. Nier shares a bit of this – the action is serviceable if not the most innovative, and while the design is inspired the technical aspects of the visuals border on the last-gen at times. Yet these remain relatively minor stumbling blocks in the face of one of the stand-out narrative experiences in the current generation.

Nier also shares in Drakengard more literally – of the earlier game’s multiple endings, the final one pulls lead characters Caim and Angelus through a dimensional portal into modern-day Tokyo to take on another transplant from their world: a huge, statue-like enemy known as the Queen Grotesqueries.

Nier‘s elliptical opening sequence sees Nier and his sick daughter Yonah in a recognizable, if cataclysmic year 2049 Tokyo before flashing 1,312 years forward to the game’s primary, less developed setting, where the same two characters apparently still exist, and Nier’s quest to cure Yonah somehow continues.

While the game eventually fills in some of the obvious questions this sequence raises, the greater backstory, including its Drakengard connections, is only implied in the game itself. It’s an interesting and somewhat brave choice to use historical and world-building elements that wouldn’t be immediately relevant to the protagonists. Fortunately, the game’s characters are strong enough to make this choice work. And a full account of the surprisingly detailed backstory is available through timelines, short fiction and developer interviews in the Japanese companion book, “Grimoire Nier.” A fan translation project exists, though be advised that there are a fair number of spoilers for the game’s later twists. To fill in some of the holes for the English speaking audience, Square-Enix commissioned three comic books and released them for free on the official website, although it doesn’t even come close to the depth of Grimoire Nier.

In short, the timeline provided in the book makes it clear that the events of Drakengard‘s “Tokyo” ending occurred in the world of Nier, essentially setting all of the world-building of this new title in motion as the two worlds collided. In some ways, it makes the apocalyptic scenario all the more unsettling – a seemingly “non-canon” battle in the previous game, occurring simply by chance an unusual setting, condemned that entire world unawares.

But to delve too much further into the particulars of the story would be doing a disservice, since a major thrill of the game, much more so than many current-gen titles that come to mind, is discovering the new twists and tragedies that are in store. Nier constantly invites and challenges your expectations, leading you through a world where there is a constant sense of unknown things, often potentially very dark, lurking just beyond the periphery of your characters’ understanding of their world.

The surface concepts of Nier don’t require much explanation – at its base level, it’s an action RPG with standard leveling, a typical mix of light/medium/heavy weapons and range of magic abilities, and reliable AI-controlled party members.

The action-RPG aspect has some interesting twists: weapons power up by assigning “words” to them, which provide a welcome level of player customization ranging from stat improvements to health-draining or exp-boosting effects. The game also takes place in an open world, albeit a slightly off-kilter one when compared with other recent evolutions in sandbox-set narrative such as Red Dead Redemption. You’re free to take on side missions between towns as you open them up, as well as fish, farm, ride a boar (and can cause the boar to drift like an OutRun car, which is thoroughly ridiculous), or even carve up felled beasts as if you’ve taken a momentary detour into Monster Hunter. Nothing is particularly necessary, and whether this is an intentional commentary on open worlds in the vein of No More Heroes, or just an underdeveloped aspect of the game is up for debate.

Press copy may tout the open world or RPG elements, but the real trait that makes Nier an absolute stand-out is its constant, almost dizzying play with genre. Each major story section tends to send you on a trip through at least one familiar, completely unexpected gameplay style, including but not limited to text sections with writing to rival Lost Odyssey‘s stylistically similar dream sequences, an isometric dungeon crawl, and even a fixed-camera jaunt to a very familiar-seeming mansion. Most bosses and many enemies tosses fire in bullet hell-style patterns, which is interesting to see from a 3D perspective. Uncovering the story’s evolving twists is compelling, but at least equally so is anticipating whatever the gameplay throws at you next.

All of these segments are pulled off within the base ARPG controls of the game, meaning that it doesn’t fall into the trap of multiple dodgy control schemes that plague some cross-genre attempts. Moreso than true cross-genre, Nier presents a series of loving homages to other genres and games. The approach (mostly) lacks the outrightly fourth wall-breaking approach of contemporary meta-minded developers like Suda 51 or Kojima, instead opting to strike the right balance that keeps the game’s own compelling internal story and characters completely intact.

One of the ways Nier builds its story over time is is through its own twist on New Game+: after your first playthrough you will be able to revisit the game’s second half, now able to understand the dialogue and motivations of the shade bosses. The effect is a bit like the moral ambiguity of Shadow of the Colossus, yet your allegiances become somewhat more complex when tempered with your extensive experience and sympathy with the player characters. Ultimately, the effect is not so much one of moral reversal as near nihilism: you are left with the tale of two sides, equally justified in their cause and equally at fault for their sins, fighting over a world that may ultimately be little more than a husk. The option to start from the half of the game where this new narrative content begins makes this second playthrough relatively painless and absolutely essential for experiencing the story.

As with Drakengard, the multiple endings don’t stop there. Collecting every weapon (again, a rather brief task of 2-3 hours even for a collection-averse player) and running through the second half again will bring you to the junction point for Endings C & D. Ending D is particularly notable for the way it pushes game narrative and player experience together: an in-game concept of sacrifice – usually a fairly abstract experience or even cliche narrative idea in gaming – becomes manifest through the literal sacrifice of your save file. While Nier may not be the kind of game that you preciously guard your save file for, with few unlockables or significant side activities, after playing through deepening versions of the game at least three times to reach that point, the choice still provides a surprising level of hesitation, as well as the ideal ending for Nier’s voyage of surprising narrative tied to surprising gameplay.

These may seem like two strange aspects of the game to link, but Nier stands as 2010’s classic case of a game overshadowed by a blend of poor marketing and excessive media focus on the wrong aspects.

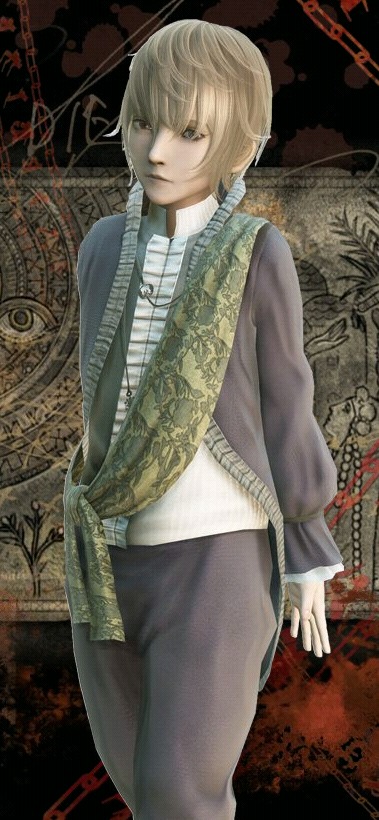

Shortly after being announced in 2009, it came to light that there would be two different versions of the game, starring two different versions of Nier – the only localized version, Xbox 360’s Nier Gestalt (Father Nier), and PS3’s Nier Replicant (Brother Nier). Initially, it was also suggested Kaine would not appear in Nier Gestalt, but whether due to misreporting or changes in development this clearly wasn’t the case. Aside from slight changes in the dialogue supporting the changed relationship between Nier and Yonah, the two versions are identical.

Cavia director Taro Yoko did eventually confirm that the two Nier designs were created to cater to Japanese and Western markets. While it’s unfortunate developers should perceive this kind of international marketing gulf, and worth discussing how these perceptions can be changed, the divide came to dominate US gaming blog coverage, to the point that it’s likely the first thing that may come to mind for someone that hasn’t played it. Far more blog space and commenting space was devoted to worrying about whether gamers’ deep sense of Gamer Morality was too wounded by the design shift to buy Nier Gestalt, than was to the truly interesting or unique aspects of the game. And that’s to say nothing of the overblown controversy of Kaine being a hermaphrodite, which largely ended up being a non-issue.

Indeed, reviews ranged from tossed-off dismissals of “fetch quest” or “downright primitive” graphics. The most misguided critical discussion came from a Joystiq post where the author extensively blasted the game, going so far as to call it soulless, because he didn’t understand how to properly read the minimap and wasted too much time on an activity he wasn’t supposed to be doing. After realizing this, the post was updated later, but with a snarky “protip” that somehow still managed to blame the game for his inability to play it. And so, one of the better known gaming blogs essentially got away with damning the release in the eyes of many of its readers.

But as much as Joystiq’s post deserves to be called out where they would not redact or edit it, Nier deserves discussion about much more than the artificial online controversies surrounding it. If one part of Nier‘s limited marketing does succeed, it is its tagline “Nothing is as it seems” – the game constantly draws you in, daring you to imagine what is around the corner, whether in terms of story, gameplay, or even the next bizzarely wonderful piece of art and sound design.

For what it’s worth, Nier‘s sole DLC pack, “The World of Recycled Vessel,” finally allowed the Western world to play as the younger Nier for its duration, which underwhelmingly consists of combat challenge rooms. He’s not accessible for the rest of the main game, though the pack does add some new costumes for the party. Otherwise, it’s not a particularly notable addition to the game.

Links:

Grimoire Nier Fan Translation Project

English Nier Wiki Surprisingly complete for a niche game, includes details pulled from Grimoire Nier in many entries.

Japanese Nier Series Site Includes great concept art and looks at Replicant.

Nier

For the sake of this article he will take the titular name throughout, but the player-namable character might be more properly referred to as The Father or The Brother. The latter refers to the protagonist of the Japan-only PS3 version entitled "Nier Replicant." The finer points of the two versions are somewhat mired in controversy, covered further down in this article, but in terms of character and story, it is sufficient to know that the sole USA version and the Japanese Xbox 360 version "Nier Gestalt" deal with an older Father Nier fighting for his daughter Yonah, while "Replicant" tells the same story only with a teenage Brother Nier fighting for his sister Yonah. This article will generally make reference to Father Nier, but the games are identical aside from the changed relationship.

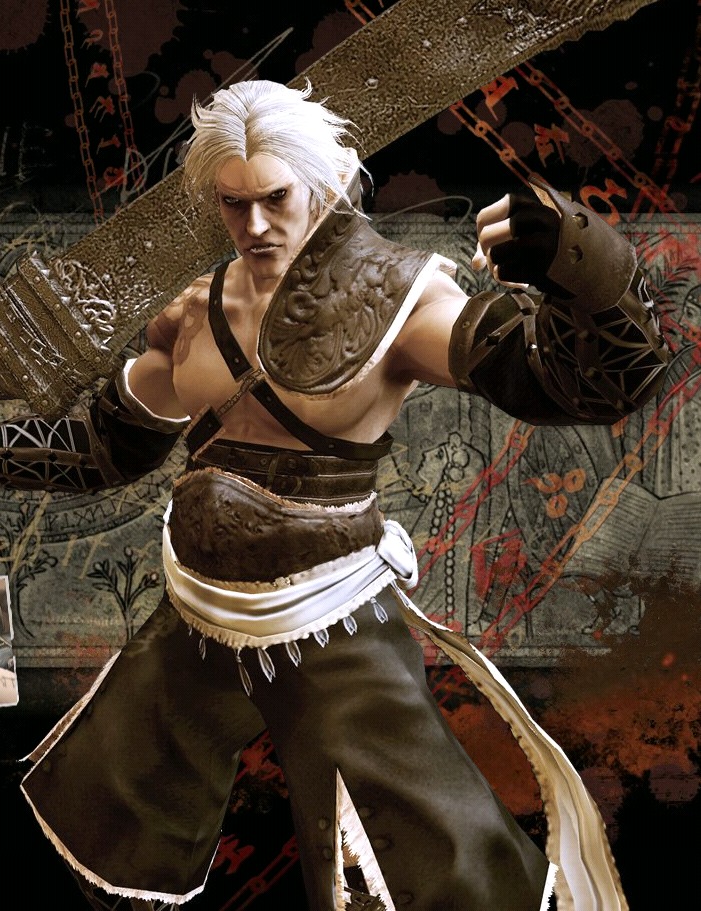

Nier is not a silent protagonist but at times fills a kind of next-gen variant on the role. He's intensely single-minded about his mission of saving Yonah in a way that may initially seem one-dimensional but as the game deepens becomes almost problematic. He's more into slicing first than asking questions about the mysteries of the world, perhaps destroying some of the answers in the process, and he is called away from Yonah's side so much during his questing to save her that he almost begins to become an absentee father (or brother).

Yonah

Nier's young daughter (who is slightly older as the sister in Replicant) is afflicted with a disease called the Black Scrawl, which causes strange black lettering to appear on her body. Almost perpetually bedridden, she doesn't play much of an active or visible role on the stage of the game world, yet the strong writing conveying Nier's devotion to her makes her the constant figurehead of your quest. In fact, near the end of the game, one of the best uses of player-side text entry since Earthbound will likely prove most player's emotional investment in Nier and Yonah's story, if the game hasn't already convinced you. Yonah's diary entries and letters frequently appear on the game's loading screen, passively enriching your insight into her thoughts and life in the village while Nier is away.

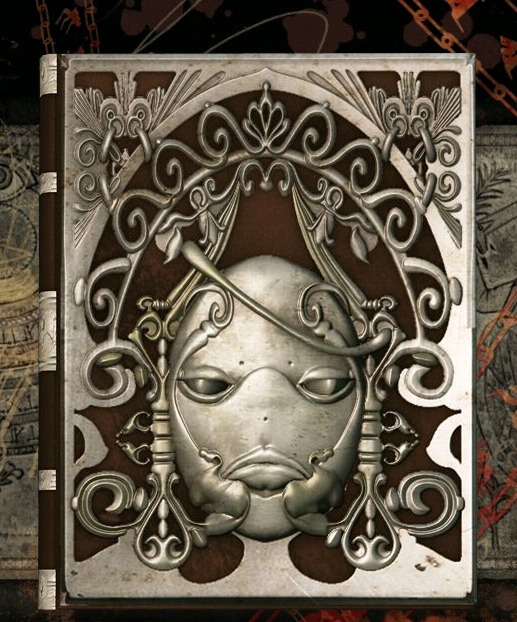

Grimoire Weiss

The sassy book with an Alan Rickman-esque voice is obtained early in your quest and enables the game's system of magic abilities. The ancient Weiss (but don't let him hear you abbreviate his name) has developed quite an ego over the years and is constantly equipped with a verbal jab for the party - often ranging into the pleasantly meta when he comments on Kaine's skimpy outfit or Nier's apparent blockheadedness. Like Kaine and other characters met along the way, he's a character that you first become acquainted with as a wise-cracking bit of comic relief, but ultimately become deeply invested in thanks to strong character development.

Kaine

The foul-mouthed, lingerie-clad Kaine is young woman scarred and possessed by a male shade. There was a bit of pre-release talk online as to whether Kaine was presented as a hermaphrodite in the game's story due to this possession, but in reality it remains ambiguous on Kaine's physical gender. A short story in Grimoire Nier suggests that she is a physical hermaphrodite in addition to carrying the shade's consciousness. While this fact could easily be played for cheap edginess, Kaine's unfolding backstory in the game is sensitively told, revealing the inner despair of someone who has been judged and treated as "other" since childhood, with the matter of whether this is due to physical or more mystical differences left off the table. It's easy to pass Kaine off as the game's token sexy character at first glance, but she quickly becomes one of the more complex female characters of recent years, as well as one of the few whose arc deals intelligently with gender identity.

Emil

Nier's story is split into two distinct halves. In the first, you encounter Emil as a kind young boy with one big problem - everyone he looks on turns to stone. He bandages his eyes and seeks your help to solve a mystery plaguing the mansion he lives in with only his butler as a companion.

In the game's second half, you rejoin with Emil and in a tragic turn of events he is transformed into "Weapon Number 7," a skeleton-like form designed in a research program that experimented on children. As with Kaine's story, the change isn't merely tossed off to hand you a shiny, strong new party member - Emil suffers considerably under his massive physical change, carrying the knowledge that it means any chance of a normal, human future he once harbored is lost. He grows close to Kaine as another whose physical otherness has condemned them to the periphery of society.

Emil is the rare well-written child character, whose fundamental kindness and even forgiveness despite his fate makes him one of the truly egood' characters even as multiple playthroughs increase the story's moral ambiguities. He, Kaine, and Weiss come to form a strange, believable family of outcasts alongside Nier that transcends now-worn RPG cliches about the power of friendship.