Although shooters have been a fixture in video games since almost their inception, the bullet hell shooter didn’t exist until the early 1990s. There are a variety of reasons for why this might be: the talent among developers had reached a point where this became viable; economic changes making niche titles necessary; or simply the continued growth of doujin video game production. Whatever the causes for the genre’s inception, few would have any trouble identifying a bullet hell game’s defining characteristics.

Ironically, it’s these same characteristics that make Night Raid such a misleading game to interpret. For as much as Night Raid implicates itself in bullet hell trends, it contradicts many of those trends throughout its design. It isn’t the game it could have been, either in isolation or especially in comparison to its developer’s previous work. Yet to dismiss the game on these grounds would be too hasty, for it is in its faults, its breaking from the tradition it claims for itself, that Night Raid explores an alternate set of sensibilities rarely found among its peers. The path the game follows, then, is both conceptually frustrating but intriguing as an experience.

This isn’t to say Night Raid‘s reputation is completely unearned. As one of the companies born from Toaplan’s collapse, Takumi had a reputation as one of the masters of the shoot-em-up craft, a reputation they would especially reinforce with their popular Giga Wing series. Night Raid, by contrast, was never designed with that goal in mind. Circumstances are partially to blame: With Capcom (Takumi’s former publisher) withdrawing their focus from arcades, Takumi was forced to publish the game themselves on a generic Taito board (as opposed to the CPS II and Naomi boards their Giga Wing games were released on), resulting in a very limited release. Even ignoring this, however, the brief and quiet promotion Night Raid received suggests that it never held any particular importance to Takumi in the first place. Giga Wing was Takumi’s flagship series; Night Raid was a small chance to play with bullet hell genre convention.

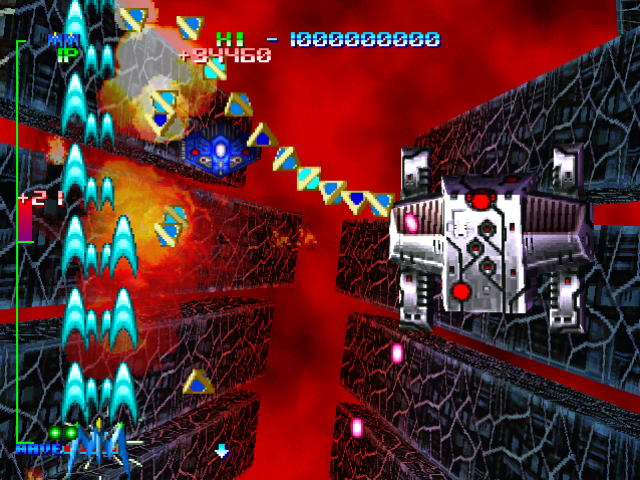

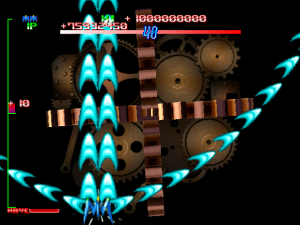

And the game’s design would appear to reflect this. A cursory glance at Night Raid is more than enough to confirm its place alongside other Takumi shooters. It shares many of the same motifs: well defined bullet patterns for the player and enemies, a scoring system built around collecting trinkets in rapid succession, timed boss encounters, and an overall emphasis on excess.

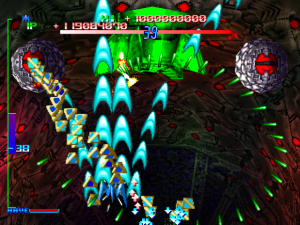

Indeed, Night Raid appears to invite these comparisons in some areas, the score thermo system being the strongest example. The idea is much the same as in Giga Wing: enemies drop trinkets upon being killed, and collecting trinkets in succession increases a score multiplier. (How much they drop roughly depends on their strength: weaker enemies drop one trinket while stronger enemies drop a line of them.) But where a missed trinket in Giga Wing only represents a missed opportunity, Night Raid actively punishes missed trinkets by decreasing the score multiplier, possibly leading to a negative score. Through the score thermo system, Night Raid frames itself as an advancement of Giga Wing‘s ideas, and because that system encourages ever finger control of one’s movements, it’s an advancement that upholds many of its predecessor’s assumptions. In theory, the rest of Night Raid should follow suit.

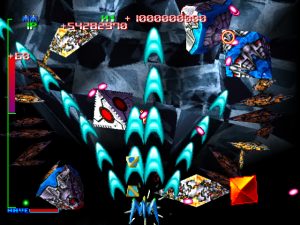

In practice, however, such a framing works to the game’s detriment, as it can only frame the game in terms of what it lacks. Compared to the somewhat ornate design of its siblings, Night Raid appears positively spartan: only a single ship to choose from, no semblance of a narrative, a single set of bullet patterns for your ship to work with. More than that, the sense of fine craftsmanship that defines Takumi’s other games appears conspicuously absent here. Loose ends and unfinished aspects are apparent throughout the game’s construction. One doesn’t elegantly weave their way through a tapestry of bullets as much as they haphazardly stumble through a ragged quilt. Arrangements and patterns have a certain looseness to them, and the wild variations in difficulty appear sudden, arbitrary, and somehow meaningless. The art style, too, evinces this: its harsh lighting is more reminiscent of an early PlayStation game than the smoother work Takumi had previously demonstrated in their work.

A more illustrative example provides itself in the Hug Launcher, Night Raid‘s special weapon. To begin with, consider Giga Wing‘s own special weapon: Reflect Force. As its name suggests, the weapon creates a shield around one’s ship that reflects bullets back at the enemy. Putting the player at risk is a function of the Reflect Force’s design; it heightens tension and reinforces Giga Wing‘s identity as a score attack game that demands high skill from its players. The Hug Launcher, by contrast, lends no such identity to Night Raid. It weaponizes the ship itself, sending it barreling into enemy after enemy so long as there’s another one to continue the chain. Although it suggests similar levels of deliberation as the Reflect Force, its lack of connection to the scoring system makes it feel less cohesive than its peer. The fact that the Hug Launcher necessarily changes your relationship with the board after using it only further exacerbates that lack of cohesion.

It would be easy enough to dismiss Night Raid based on these supposed failings. Yet were one to take this route, they would struggle to reconcile those failings with the complexities of the game as they’re experienced. Regardless of any misgivings, the score thermo system works exactly as it should, encouraging players to engage what the game has to offer in as much depth as possible by making those players zip about the board to increase their score. And in addition to those failures’ inability to prevent the game from functioning, it’s hard to ignore the undeniable charm Night Raid possesses, if only because of how forceful that charm is.

At best, the previous analysis can only establish how not to the interpret the game. How, then, does one properly approach Night Raid? In short, on its own terms. To clarify, the ideal the game pursues lies not with control, but with power and intensity; the ability to leave as forceful an impact upon others as possible. It goes out of its way to create chaos, disposing of everything unnecessary to realizing its vision and exaggerating anything that makes the cut. By far the most notable part of Night Raid‘s vision is the confidence and zeal with which it pursues it, guaranteeing it a definite level of charisma.

Probing things further, one finds that singular desire to make an impact enable far more from Night Raid than it would inhibit. Where other bullet hell shooters adopted a semi-serious attitude toward their subject matter (Ikaruga, Raycrisis, etc.), Night Raid refuses to take any aspect of itself seriously. All the better that it doesn’t, since camp exaggeration represents another path to raw power – the hammy announcements upon powering up or using the Hug Launcher, the erratic paths the Hug Launcher carves across the screen, the way weapons violently shake the screen upon use. Furthermore, because its ultimate goal is to entertain and because it can achieve what it wants through mostly audiovisual means, Night Raid is a surprisingly accessible game. It may still be a bullet hell shooter and everything that implies, but so long as its own goals are achieved, the game is content to keep bullet patterns loose or to forgive players for colliding with an enemy ship.

At times, these tactics can prove a detriment to Night Raid. Putting aside the loose structure they result in, they deprive the game of dramatic arcs and can thus flatten the action in some areas. Yet just as often the game’s exaggerated tone proves an invaluable asset. It’s what lends the game its basic but undeniable charm, and what makes Night Raid such a stark contrast to the more refined and nuanced genre work that defines its contemporaries. In this regard, one might read the game as a half rejection of the bullet hell shooter scene. It may accept some of the genre’s basic premises, but in applying them to an aesthetic project outside that genre’s typical subject matter, Night Raid inadvertently refutes a lot of the motifs bullet hell shooters are known for. While this can, at times, make the play experience a hard to discern one, it also guarantees the game’s status as an intriguing object of study.