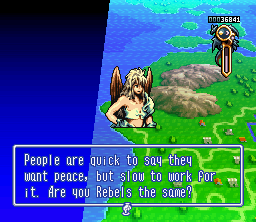

When it comes to politics, Socrates had it right. It’s all about the question: what is justice? The entire process of governing really comes down to, who gets what, and why do they deserve it. War, then, is a clash between “deserving” claims, or visions of justice. In Yasumi Matsuno’s Ogre Battle saga, the scope of this question is tested in a series of strategy games that examine wars from multiple points of view, continually forcing the player to ask themselves: am I doing the right thing?

Intricate storylines and mechanics grace these titles that are involving in a way like no other. The series stands as one of the pillars of the strategy RPG. Revolution, rebellion and conquest make up the backdrops for engaging tales interweaved with excellent systems in both real-time and turn-based installments.

One of its best elements is its portrayal of the interplay between strategy and tactics, in terms of both a game as a story-telling device and a game as a platform for its mechanics. Throughout the series, the objectives of battles, and the ways they are fought are presented as serious questions of political ethics. Meanwhile, the player must formulate general plans for each mission, and still excel at specific maneuvers when it comes to the head-to-head clashes between units. Being two sides of the same card, Ogre Battle saga is all about choosing the “best path”.

In 1992 the nascent Quest Corporation was encountering difficulties in the burgeoning, yet competitive industry. Despite several releases for the Famicom, Game Boy and NEC-PC 8801, they lacked exposure and prestige. In order to garner these, they needed to make a unique game. For this aim, they turned to planner Yasumi Matsuno. After three years of studying foreign policy at Hosei University, Matsuno left to pursue his dream of becoming a writer. Finding work as an economic reporter helped him get by, but the intimidating corporate hierarchy and its rigid structure reminded him of his longing to be creative. He wondered whether he might be able to put his writing skills towards making games, and left his job in search of that chance. In 1989 Matsuno joined Quest at the age of 25. Having recently renamed itself from Bothtec, the company was looking to establish a fresh corporate identity, and was looking for new people. Despite lacking experience in the game industry, Matsuno was placed in a position of responsibility from the outset, leading the design on Conquest for the Crystal Palace, a 1990 NES platformer.

Thinking on the type of new IP that would draw attention in the Super Famicom era, Matsuno decided to create a real-time simulation (strategy) RPG, banking on the niche appeal. While being more of a fan of action titles, Matsuno appreciated the approaches found in Nobunaga’s Ambition, with its grand strategy scenarios, and the turn-based Daisenryaku. Master of Monsters influenced his choice to use a fantasy setting, thinking that that would make the new title stand out.

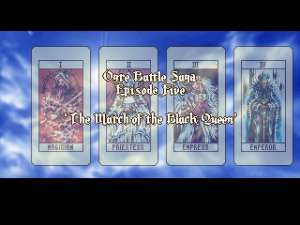

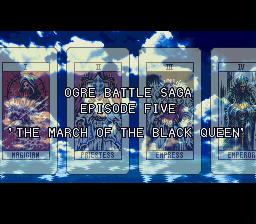

His love for the band Queen led him to titling it Ogre Battle: The March of the Black Queen, combining the names of two songs from their album Queen II. Working from a rough idea of an eight-part fantasy epic, he envisioned Ogre Battle as “Episode V” and went from there. Primarily, he was driven to go beyond a simple good vs. evil framework, and frame the conflict around moral ambiguity. The player may choose to be a liberator or competing conqueror from the outset, and antagonists are often shown as having valid motives.

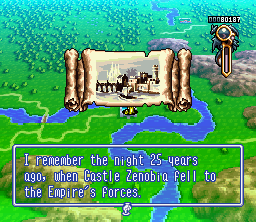

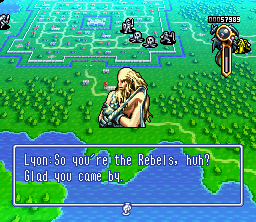

Ogre Battle is set during the Age of Zeteginia, a time where might makes right, and iron clashes with steel. In the kingdom of Zenobia, the beloved King Gran has been assassinated by the Sage Rashidi, who has allied himself with the self-proclaimed Empress Endora and helped her to subjugate the land. A few years later, the royal Knights of Zenobia leave their island hideout and join a lord, the player character, in a campaign to take the country back.

Characters

Destin Faroda

The player character, a silent protagonist leading the rebellion. Later given an official name in Ogre Battle 64.

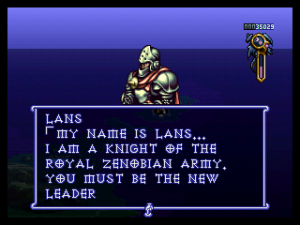

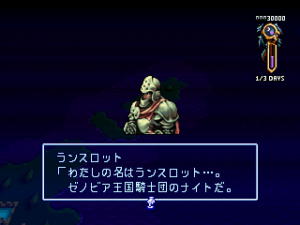

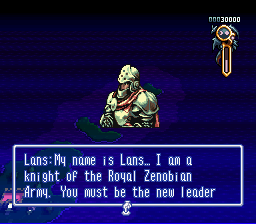

Lans Hamilton

One of the first allies in the game, the archetypal white knight.

Warren Moons

Since Lans is a reference to Lancelot (it was his name in the Japanese version), Warren is definitely the Merlin of this game. Offers sage advice and later becomes a historical chronicler in Tactics Ogre: Let Us Cling Together.

Gilbert O’Brien

Governor of the Sharom district whose story introduces the “gray versus gray” morality of the series.

Canopus Wholph

Close friend of Gilbert who helps win him over to the rebellion. Becomes more fleshed out as an “honorable rogue” in the next game.

Deneb Rove

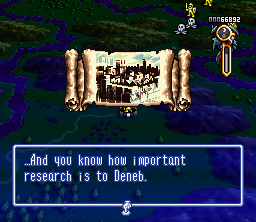

“Mad scientist” witch who experiments on humans to create pumpkinheads, plant-hybrid soldiers that become both her, and series staples. Giving her amnesty after the boss fight is one of the early moral dilemmas, alignment-wise.

Kaus Debonair

Honorable warrior of the Empire’s Four Devas (think Elite Four). Demoted to the boonies for pulling an Eddard Stark in the face of official policy.

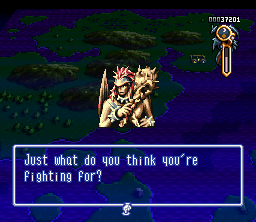

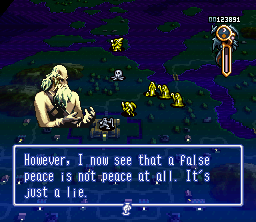

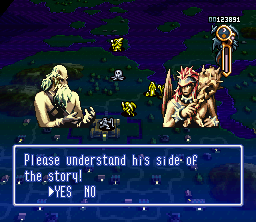

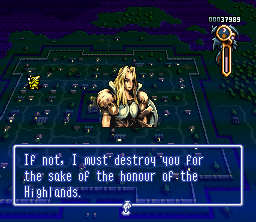

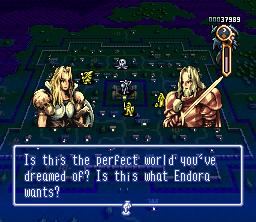

Some of the enemy commanders may be recruited to the player’s side, and these interactions detail the moral ambiguity Matsuno was going for. The beast tamer Gilbert, while opposed to the Empire’s evil ambitions, joined them to protect the people of his region from their attacks. The witch Deneb experimented on humans to create living weapons; interestingly, while mercy is often portrayed as the “right” thing to do, sparing her life will result in losing the faith of the people. Granting amnesty to the defeated, and treating with the enemy are among the scenarios presented to the test the diplomatic mettle of the player; while hardly a serious simulation of foreign relations, that the player is constantly presented with situations that test what kind of leader they wish to be is one of the reasons Ogre Battle is a seminal work.

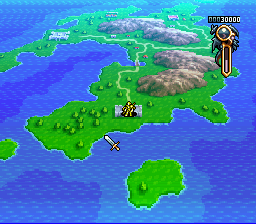

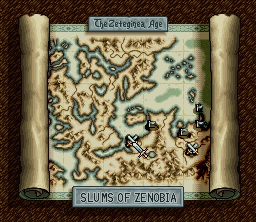

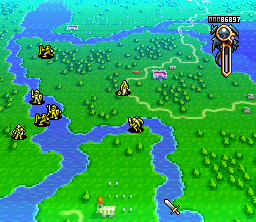

Each stage consists of a map of a region, dotted with fortresses and cities across the landscape. A stage is cleared when the enemy HQ is captured, after defeating the boss. Losing the player HQ or getting the main character killed results in a game over. At the beginning of each stage, the main character’s unit sits at the home castle, and the player must figure out an approach to taking the map. This involves some macro and micro-management, and balancing the two just so.

The player can deploy up to ten units on the field, including the commander’s. Generally, one needs to proceed onwards, taking towns as they go, to work as footholds for the last charge at the boss. Once the player holds a city, units recover HP resting there between fights, so long as it remains in the player’s possession. Of course, the enemy AI is marching at your HQ at the same time, and it becomes a great balancing act of attempting to fortify your defenses while pushing them back. Much of the game is thus telling your troops where to march, setting up positions to surround the enemy, holding vital choke points, and so forth.

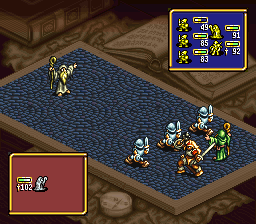

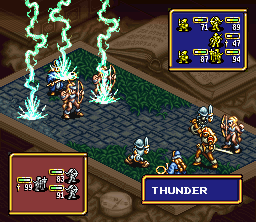

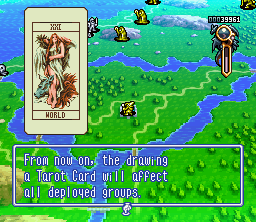

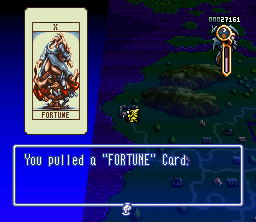

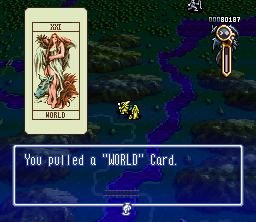

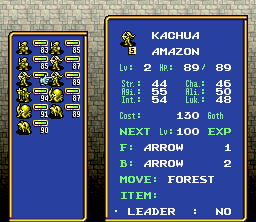

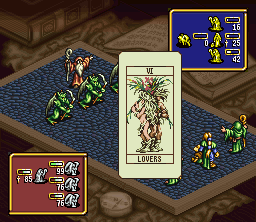

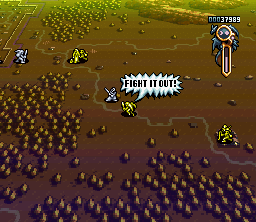

Positioning units on the field matters so much as it does because when units meet, there is little direction as to what attacks they take. They can be helped by Tarot cards-special attack, healing and stat buff “items” dropped after capturing a city. The unit can be told to flee, or change its primary target. Yet other than these options, characters automatically attack each other in a turn order determined by their agility stats. What they do in fights is determined by their formation. Some characters are static and simply attack, while others will use different skills in different rows. The player must organize their units to maximize damage against the enemy, without overexposing themselves to attack. At the end of three rounds of fighting, the battle ends, and the loser-the unit which dealt less damage-is pushed back several “miles” on the field map. In the case of a draw, both units are pushed back.

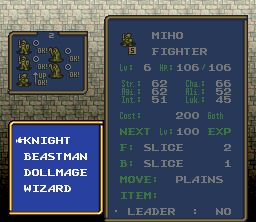

Planning between stages thus involves a great deal of customization. Forming well-rounded units requires a concern divided between formation, abilities and attributes. Characters progressively get stronger by leveling up, and can be bolstered by buying them new equipment. Yet there is also the option to change their classes, provided their combat stats are high enough in the right areas, and their alignment matches the class type. For instance, users of holy magic like clerics need a high alignment meter, so grunts with a low alignment stat can’t promote to that class.

Alignment is another of the intricate connections between the macro and micro aspects of this game. Cities can be either “captured” or “liberated”. For a city to be liberated, the alignment of a unit’s leader must match the alignment of the population. High alignment units that try to take low alignment towns will end up capturing them, and vice versa. As the liberations add up, the alignment of the player character raises, representing the faith of the people. In order to get the “best” endings, player alignment must be high, so choosing unit placements has a direct impact on the overall outcome. Additionally, special characters with a bearing on the storyline – and greater abilities in battle – will only join if alignment matches with theirs. Even the individual fights puts alignment in flux, as if units commit “dishonorable” actions, like killing weaker enemies, or chasing down enemies whose commander has been killed, alignment drops; doing the opposite nets a boost to the stat. Even disregarding this system leaves the player with a comprehensive challenge. Most maps feature waves of stronger enemies. Early on, it becomes clear that one cannot simply throw guys at the boss and expect to win.

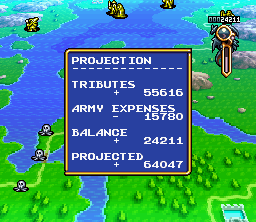

There is also light economic management to consider. Deploying units costs money, and maintaining them on the field incurs daily expenses. The better the character, the more expensive it is to send them out. Strongholds acquired will pay tribute daily, making keeping them a priority. Casualties are inevitable, and resurrection costs three times the deployment cost of a soldier.

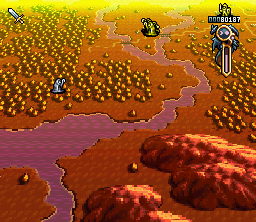

The art direction was led by Hiroshi Minagawa. While many field maps consist of gray blobs on vast swathes of green, mingled with the occasional patch of blue, they get the job done. Where Ogre Battle’s style really stands out is within the battles, and the illustrations for characters, cities and Tarot cards. The fights take place in a background draped by an unfolding book, with maps and instruments scattered about, highlighting the atmosphere of epic historical conflict. In-battle character sprites use only nominal animation, yet the actual designs themselves are magnificent. The character art was illustrated by Akihiko Yoshida. His work on the Tarot cards is fanciful and grandiose, and strikes a sharp contrast with the cruder, starker character portraits. Both are excellent, and critical to the overall atmosphere.

Composition of the musical score was handled by the team of Hitoshi Sakimoto, Masaharu Iwata, and Hayato Matsuo. Despite working with MIDI sound files, their aim was to create an orchestral-sounding score to reflect the dramatic tension of the piece. For this, they used a Roland SC-55 sound module to achieve a symphonic sound electronically. Matsuno collaborated heavily with them in this to ensure the mood provided was just right. The conversion to the SNES sound format was successful, and many tracks are quite stirring. Both versions can be found on the official soundtrack release.

It’s a complete success; the themes played on the field are punctuated by verve and vigor, conveying that rousing, “marching off to battle” feeling. The stress of a tough battle is emphasized by the taught notes played. The victory melodies are punchy, and when battles are lost a vexing decrescendo highlights the failure. It’s an interesting work, foreshadowing the partnership between Sakimoto and Iwata and their now-famous take on classical music-the real debut of a legendary partnership.

Finding its mark, Ogre Battle gained a reputation as a difficult and rewarding game, building anticipation for the next project from Quest.

Ogre Battle found enough popularity in Japan that it was ported to both the PlayStation and Saturn. Meanwhile, in North America, the SNES edition received spare distribution, with few copies available, so the PlayStation version was localized as a “Limited Edition” in order to draw in potential fans that missed it the first time around. Both versions have their own unique changes and additions.

While the core gameplay remains largely the same in its PlayStation release, there are numerous changes that affect the tone, and can thus greatly impact the experience. The changes to the script especially bear mentioning. Each chapter begins with a prelude – a la the text scroll in Star Wars – setting the stage. Greater explication is what this story needed. Not only is the localized text crisper, but the font is radically changed, resembling the Exocet font, as made famous by Diablo. This works, because Ogre Battle is a medieval world that lives and breathes as if mythological times are only a few centuries past. On top of this, the names of several cities have been changed.

Though the visuals look mostly the same at a glance, there are some subtle differences. The character animation is more dynamic in battle. The backgrounds are now composed by polygons while the combatants are still sprites. Although looking more “next-gen” for its time, it takes away from the original design, which gave the impression of an illustration come to life. The spells of the wizards include new animations, often with 3D animations, which look fantastic. The camera zooms in on a spellcaster as their magic flies across the screen at the opponent. Both elements make battles far more exciting than before. Beautifully, the Tarot animations now feature completely rehauled presentations, zooming in much like spellcasters’ attacks, dazzling the eye and dominating the screen.

Not only is the sound quality higher on the PlayStation version, with updated sound effects across the board, but the songs have been reworked to take advantage of the PS1 sound chip, with a symphonic feeling that rings triumphant. There’s even a voice over added for the introduction.

The most interesting feature may be the demarcation of a unit’s path when assigned its marching orders. A red line crosses the map from their starting point to the destination, helping the player visualize their movements. This is not only cool from a historical simulation perspective, but useful strategically.

Riverhill Software handled the port to Saturn, which was only released in Japan. Its changes are different from the PS1 version. Every unit on the world map is in full color. From Destin’s scarlet attire to the green of a wizard’s robes or the purple trim samurai are adorned with, every unit is represented on the map with their signature colors, rather than as static gold. Instead of static grey, enemy units are rendered with a darker color palette. It lends your troops identity as they meet a wave of opponents on the field. The only drawback in this sense is when any unit loses it leader, the icon changes color to a pink-green-yellow mishmash akin to a tye-dye shirt. It’s an odd change of tone, but worth bearing with as the rest of the map looks wonderful with this change. When units enter or leave a stronghold, they are animated so as to turn and face their destination, allowing you to even see their back and bodily movements as they move about. When a unit is assigned movement directions, a “marching” sound effect even plays afterwards, a big change from a static block moving from point to point. However, otherwise the visuals are mostly identical to the SNES version, other than expanding the resolution to 320×240 over the SNES’ 256×224.

The other great change to the stages are represented by camera angles, and unit display options. A new spin is given to the default camera. It’s now on a slightly tilted angle, allowing one to see the curvature of the earth as landmasses stretch across the water. This also means more visual dimensions to discerning the time of day. A glimmer of sunset can be seen on the horizon as day turns to night, rich reds contrasting with the vibrant greens of the earth. This detail really makes the world feel alive. Zooming way out to assess the entire map is still present, while an added third angle gives a strict overhead view. This is interesting, as it conveys the tone of either a traditional RPG or Fire Emblem in how it presents unit distance, and helps with gauging their positions, as the default view can at times be so angled it obscures them.

Pressing “L” brings up a new format for the unit list. To the right of the units a minimap is displayed, including territory, enemy and ally positions, and the placement of strongholds. This functions as a radar and is a fantastic feature for organizing your troops during those tougher moments. When deploying units, a display of their formation pops up to the right, allowing the player to directly assess the unit’s strengths and weaknesses, rather than just relying on remembering the unit composition based on its leader’s name.

Other flourishes have been added to the menus. For instance, on the organize screen new illustrations have been added for the various options. After buying items, item types now group together collectively, rather than staying as clumps of 6 potions here, and 11 potions there – one of the better practical modifications.

Its best feature may be the addition of professional voice acting for the dialogue of major characters. When you meet heroes like Lans, Yulia, and Canopus their nobility, courage and determination shine through. Every boss encounter is made all the more menacing by their attempts to intimidate you beforehand. The sound has been improved over the SNES version, though it sounds a little different from the PS1 port. Several tracks are played via redbook on the Saturn whereas only a few tracks are done like this on the PS1.

These are great improvements all around, but both versions suffer from the same issue that plagued almost every other 16 to 32-bit port: load times. The wait times in and out of battle is especially excruciating, and even though the improved visuals and sound are great, the blow in the pacing can render these ports frustrating, if you don’t have the patience for it.

After this game, the Ogre Battle series took a different direction, with the Tactics Ogre SRPG spinoff. It returns to this type of gameplay with two successive titles: Ogre Battle 64 for the Nintendo 64 in 1999, which is heavily revamped, and Ogre Battle Gaiden for the Neo Geo Pocket in 2000, which is fairly similar to the original Ogre Battle.

Screenshot Comparisons