- Ogre Battle

- Ogre Battle Gaiden

- Tactics Ogre

- Ogre Battle 64: Person of Lordly Caliber

- Tactics Ogre: The Knight of Lodis

Following the cult attention lavished upon Tactics Ogre, Squaresoft wished to replicate that effect for its flagship franchise. Matsuno, Yoshida, Sakimoto and other key members of the Quest team were brought over to create Final Fantasy Tactics in 1996. As such, until the remake of Let Us Cling Together, the remaining Ogre games lacked Matsuno’s direction, yet still tried to follow his story premise. Despite Matsuno’s departure, the remaining team excels in this entry. Quest initially wanted to title this installment “Ogre Battle 3“, but as their development partners, Nintendo, insisted upon calling it Ogre Battle 64 to emphasize its exclusivity to the N64 platform.

Person of Lordly Caliber is Episode VI in the Ogre Battle Saga, being a direct sequel to March of the Black Queen. It concerns itself with the aftermath of the Zenobian Revolution and its effects upon the internal conflict in the neighboring state of Palatinus. Before stages, an ominous sinking sound echoes, followed by a view of the title as if you were underwater…as if you were a stone sinking to the bottom. It’s a beautiful metaphor for the game’s story. In a press release from the time of its debut, Quest declared it wanted to explore the traditional foci of Ogre games, the questions of why people fight, and why they hurt each other. While they recognized the series often put it upon the player to answer that themselves, they felt this story provided a worthwhile answer in its own right.

Palatinus is a prosperous country that has been ruled indirectly as a tributary state of the Holy Lodis Empire for several years. As a result, the already hostile relations between the upper classes and under classes have intensified. Lodis’ influence led to an imposition of harsher rule, restricting rights for all but the privileged; as social problems exacerbate, both residents of the poor southern region and members of the Indigan minority are targeted as scapegoats, continuing a cyclical “war on poverty”. The south rebels, staging its revolt by capturing the heir to the throne, Prince Yumil. Yumil’s childhood friend Magnus Gallant has just graduated from the Ischka Military Academy, and is on duty suppressing the rebellion when he hears of the kidnapping. After rescuing the prince, he fights against dissident forces and learns the established social order is not all it appears to be, and joins the side of the resistance.

Person of Lordly Caliber features a fantastic narrative. Unlike March of the Black Queen, it features lengthy cut scenes between and during missions. The plot and character motivations are extensively detailed, unlike Black Queen whose story was largely told through boss encounters and running into a random villager after liberating a town. As opposed to the “Warren Report” in Tactics Ogre, there is now the “Hugo Report”, which is much the same, but for one major feature. It contains a genealogical/political relation tree that branches across every dynasty and faction.

Its only shortcoming in the story department is how it pales compared to Tactics Ogre. While there are a decent amount of branching paths and several dialogue choices, by and large Magnus leads the fight against the occupying Lodis army. It is by no means “rag tag group of misfits defeats the overwhelming empire” – but the moral ambiguity and terrifying circumstances conveyed through Tactics’ tone are missing. Yes, the story goes to some pretty dark places, but even making the “wrong” choice still leads to becoming the liberator fighting oppression. In that sense, they are telling Magnus’ tale more than you are choosing who Magnus is to be.

However, few games focus on socioeconomic disparities as major plot points. The difficulties faced by the Indigans are those encountered by internally displaced peoples’ today. Lodis’ imperial policy is strikingly similar to the treatment of colonial peoples by historical empires. Elitism and egalitarianism are intrinsically opposed, with the gap between the high and the low necessarily causing tension; these are themes worthy of consideration, and Ogre Battle 64 paints a cruel portrait of medieval life while serving up contemporary social commentary.

Fundamental gameplay remains largely the same as March of the Black Queen, yet there also many new features added which alter the experience significantly. Individual units are made both more indispensable and disposable at the same time. In the first title, characters killed in battle are instantly restored to full health after the completion of a stage; here, they become zombies if you don’t pay to resurrect them at a witch’s den before the stage ends. Zombies are drastically weakened versions of standard characters…yet retain the ability to later change classes into undead powerhouses like liches. This a creative implementation of a permadeath system that challenges the player to take care of their characters while still keeping their options open.

At the start of the game, the player is given a pool of soldier reserves. These are groups of three guys who are treated as one character unit. They are incredibly weak human shields, but after enough experience, one of them levels up into a standard fighter. As their HP gets lower, another of the three will die, but they can be replenished from the pool. Each stage awards a number of additional reserves, which is an interesting historical simulation mechanic – they can be thought of as forced conscripts or would-be revolutionaries.

Deployment costs for units are now eliminated; you also no longer collect tribute from captured cities, only receiving Goth (the currency) after completing a stage. War funds are now no longer directed towards maintaining the army on the field with mandatory daily expenditures, but are instead used mainly to buy healing items and the armor/weapon upgrades that come along. Since there is now a greater emphasis on taking care of each individual character, this frees up the resources to do so. Micromanagement is improved not only through a slicker presentation of menus, but their functionality as well. For instance, instead of highlighting each individual to see if they’re eligible for a class upgrade, collapsing the menu and repeating ad infinitum, a class change check on all characters can be conducted en masse. Equipment can even be bought at the organize screen between missions, rather than only from the towns with shops within the missions.

Whereas in March of the Black Queen the interrupt command for battles lets the whole range of options fly with any pause, in Ogre Battle 64, there’s an almost ATB-like quality to the gauge. At any time, tactics can be changed (assign target). Not until the meter charges to “2” can the player run away. At the count of “3”, Elem Pedra, the replacement for Tarot cards, can be used. This is an elemental-magic super-move which nearly guarantees knocking out the entire enemy party, unless it’s the boss. Critically, it takes an incredibly long time to recharge, so it’s a great mechanic for clinching close battles that isn’t easily abused (of course, sidequests can unlock the other three Elem Pedra that are not tied to Magnus’ affinity, allowing for a potential stock of four). Pressing the start button will trigger a “Field Pause” implemented immediately after the battle stops; for an Ogre Battle title, this is a major update, as this can give that last chance to heal a weak unit before they get ambushed.

Another major change is unit facing. A unit’s formation in battle will be determined by whether they meet the enemy head on, or get flanked or routed. Since the targeting range and damage output of characters is determined by their positioning on the unit grid, this makes placement and movement on the field all the more thought-provoking. On that end, units now actually get tired after marching. They need to periodically set up camp, or rest at a fortress, to recharge their stamina, otherwise they will unilaterally camp out when their stamina gauge reaches max. Being caught by the enemy while resting upsets formation, so this system really weighs in on the dynamics. It’s an excellent simulation element that really adds to the campaign feel.

Directing units now has more to it. Their target can either be a fortress, enemy unit, or general location. They can even be assigned behavior types, ie. aggressive or avoidant in the face of enemy units. While attacking resting enemies or flanking them confers an advantage in battle, such “dishonorable” tactics leads to a loss of alignment for both those characters and Magnus. The “Reputation” meter is gone, replaced by the always unseen “Chaos Frame”, a tally of moral choices and alignment scores. While making the right choices in the story can have a decent impact, the majority of the results come from whether towns are captured or liberated, and where character alignment stands, just as in the first game. It can be disconcerting to get a bad ending after playing as a champion of social justice, but to be fair, you are repeatedly told about the importance of securing the trust of the people, and it is an evolution of the system from the first title. Not only is it a more involved gameplay experience when attention is paid to the Chaos Frame, but it is another part of the historical simulation aspect of the series; how a leader is judged should not just be determined by treaties and policy choices, but also how they conduct themselves on a day-to-day basis.

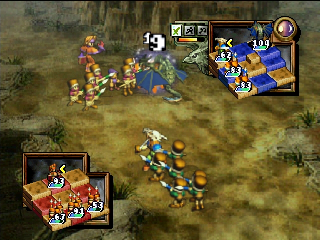

While many titles of the N64/PS1 era used ugly, blocky polygons to illustrate their worlds, Ogre Battle 64 largely relies on 2D art to great effect. Field maps are in 3D, yet cutscenes and battles – the bulk of the game – look like a painting in motion. This was a bold choice, and no other N64 entry quite looks like it. Aesthetically, it follows the template of Tactics Ogre: grand battles are punctuated by intimate scenes that reflect the motivations of characters and nations, highlighted by the contrast between realistic character portraits and super-deformed sprites. Another great use of contrast is how magic attacks are animated. Spells are rendered in 3D and naturally overlaid into the scene, both standing out and flowing with the action.

Approximately a third of the tracks for the game are reappearances from March of the Black Queen and Let Us Cling Together, with new arrangements by Hayato Matsuo. His new takes on the material enhance the originals with dashes of inspiration while evoking nostalgia for the first titles. Most of the original songs are his work, with some input by Iwata. This approach seems to be the best take for what Ogre Battle 64 is: the third game of a cult franchise. Fans would be expecting to hear the compositions they first fell in love with, which dominate the cutscenes, yet would still want something fresh – Matsuo’s new songs are set to the fights and field maps, where Ogre Battle 64 shows most of its innovation.

It may be that Ogre Battle 64 is one of the best strategy games because it combines the “freedom” of the RTS field with the “restrictions” of the SRPG grid. Each approach has its strengths. Commanding several units over a vast map is like being one of the great generals of old, forced to parse out the big picture in a tapestry of conflict. Ordering around select units on compact terrain is like leading an elite squad through a desperate struggle. Both approaches to strategy have their own limitations imposed by design – the creative venue for the player to find openings. This is what makes it so satisfying to see the battle end as fireworks dart the sky.

Ogre Battle 64 is a triumph, and takes its place as one of the core entries in the series.

Characters

Magnus Gallant

Son of a disgraced general, Magnus is an idealistic and capable man who quickly earns favor in the Southern Division suppressing the rebels. Despite being born and raised in the capital region, and being close friends with Prince Yumil, he remained away from home after graduation, and accepted assignment on the frontier.

Yumil Dulmare

Passionate and kind-hearted, second-in-line to the throne of Palatinus, he is determined to gain power to secure peace for the kingdom. Separated by the trauma of their youth, he has not seen Magnus since he lived in the capital.

Diomedes Rangue

Hot-headed warrior who serves with Magnus in the Blue Knights. Also serves as a foil to Magnus’ cool, he can be one of his fiercest supporters. Personally marked by the discrimination against Indigans, he carries a chip on the shoulder.

Leah Silvis

Heir to a noble line who joins Magnus’ battalion at the outset; driven to prove herself as a warrior. While initially made out to be a major heroine, unfortunately receives little character development thereafter.

Destin Faroda

The hero from the first game, now obtainable as a special character. Allied with the revolutionaries, he is one of the first to challenge Magnus’ notions of justice.