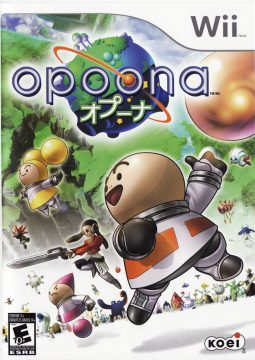

Opoona is a quirky, sci-fi themed RPG, released in 2007 for the Nintendo Wii. Not only was it produced by longtime Dragon Quest veteran developer ArtePiazza, it was one of the earliest role-playing games for the system, ready to spring into a still-empty niche. Yet it tanked and it tanked hard, even in its native Japan. How hard? In Japan, it released the same day as triple-A ultra-mega-title Super Mario Galaxy, but even in North America and Europe, where it launched significantly later, it failed to find its footing. Moreso than its quality, this it perhaps a sign of the sort of RPG Opoonachose to be: Not the standard, high-fantasy gold-‘n’-grind fest, not an epic, sweeping tale of good versus evil, no battle-hardened teenagers with spiky hair in sight, but a rich, dense, and almost impenetrable world-building experience for the handful of people seeking exactly this sort of game in the first place. And it’s told through the eyes of a trio of Playmobil-esque alien children whose summer vacation has just gone horribly wrong.

Characters

Opoona

Our heroic mime, primary protagonist, and designated melee fighter. Described in the manual as a “carefree big brother,” but, due to his mime-iness, his personality is mostly whatever the player chooses to make of it. Also a top-notch dancer and ukulele player.

Copoona

The second party member and magical powerhouse. A sweet and caring little brother. On Landroll, he takes the job of healing people with his magical powers, and his calm demeanor combined with his friendly personality make him a popular guy.

Poleena

The third party member, who even gets to spend some time as protagonist away from her brothers. She strikes a balance between magic and melee powers, and can talk to spirits. She’s a fiery go-getter who is always quick to take initiative.

Dadeena and Mameena

The parents of Opoona, Copoona, and Poleena. They’re among the most respected of the Tizian warriors, but have been put into a coma due to the injuries they sustained in their ship crash. Now, their children must save them.

Chaika

A young girl who multitasks almost as much as Opoona does, being both a powerful Landroll Ranger as well as an inventor and big company shareholder. She’s friendly and chipper, but fierce in battle. She and Poleena become good friends.

Goldy

Head of the Landroll rangers, and mentor to Opoona. Good-natured and generally lovable, despite his pugilistic profession. He’s extremely loyal and sticks to his principles, but rumor has it he’s torn between loyalties…

The story that actually kicks off the game is almost RPG 101: Someone’s in trouble. Save them. Our protagonist Opoona is the eldest child of what we shall call the “Na” family, which consists of parents Mameena and Dadeena, and children Opoona (orange), Copoona (grape), and Poleena (lemon). They’re members of the Tizian race, a storied alien species who have long been the protectors of peace in the galaxy. Their spaceship malfunctions en route, and crash-lands on the planet of Landroll. Opoona, Copoona, and Poleena safely jettison in escape pods, but Mom and Dad crash with the ship, and are sent into a recuperative coma. So now Opoona must plumb the depths of Landroll to amass mystic minerals called Matia in order to heal his parents. It sounds like the set up to a perfectly ordinary and respectable RPG, perhaps one spent traversing eight elemental dungeons to collect themed Matia crystals. But then the game throws a curveball: “Matia,” in addition to being a mystic power source, is also used by Landrollians as money. And how do you get money? By getting a job (or several), of course.

The planet of Landroll is a massive, tangled web of bureaucracy and social networking, and Opoona’s success in his quest will be determined not by his skills at boss-stomping, but by his multitasking abilities and his societal maneuvering and his integration with the culture. Opoona has to carve chunks of his busy monster-fighting and boss-stomping schedule to visit with his Facebook friends and practice his dance steps for his premiere on intergalactic TV if he wants to heal his parents. Of course, this is an RPG storyline, and the game would be remiss if it didn’t work a little world-saving into things, in the form of a Dark Force threatening the world from an ancient meteor that slammed into the planet. But even the Dark Force is wrapped up and integrated into the vast net of Landrollian society, and many of the base aspects of Landrollian culture are informed by the need to keep said Dark Force at bay. Similar to the novels of Victor Hugo, where the setting is as much a starring character as the protagonists themselves, Opoona is as much a game about the world of Landroll, how it ticks, what its people are like, what its history is like, and its day-to-day life as it is about the three little Playmobil aliens trying to navigate it.

Landrollians live in giant cities-under-glass called “Domes,” because their seemingly idyllic wildernesses are teaming with malicious, invasive, and literally alien species known as Rogues. In order to keep these claustrophobic dwellings in order, Landroll implemented a series of jobs and ranks to ensure that every citizen has a station and role in society–even outsiders like Opoona. Everything in the game is tied to jobs on Landroll. Opoona gets to go to new cities by receiving new assignments in those cities. He receives money by completing certain jobs. Getting to certain levels in each job gives him the right to do other jobs, which can grant him new skills and abilities. Jobs let him meet new people. Jobs help him boost his stats. And each job has something to teach him about Landroll’s culture. Take the Farmer job, for example, and he’ll learn all about how the once-proud farming tradition on Landroll has been subsiding now that the wildlands of Landroll are almost uninhabitable and more food production has become artificial. Take the Clerk job, and he’ll get to visit fancy hotels and location spots way out of his league so he can hobnob with the societal elite. He can even become an Art Coordinator and visit the game’s several museums, where he can catalogue the 50+ works of art in the game, with their associated art history lessons on Landroll’s prevailing schools of artistic thought.

Opoona’s primary job, of course, is the Ranger job, which is the one that lets him beat up monsters, retrieve plot trinkets, and explore dungeons in classic fashion. But even then, the game doesn’t let the player brute-force their way through to the resolution. Planning director Sachiko Sugimura wanted to create a game around the idea that “every single person means something,” and as a result, the game both encourages and enforces socialization. Throughout the game, certain special characters will agree to become Opoona’s friends, and will add him to their social network. By talking with them regularly, building his stats, and going on sidequests, he can advance his friendship level with them, gaining more stats and rewards in return. Come the final dungeon, Opoona learns that he needs to assemble a crack team to storm the enemy base with him–and only those friends who truly trust and feel close to him will have the nerve to join him by him side. It’s a design decision that most rewards the sort of players who go back to chat up every NPC after every significant gameplay moment to see if they have anything new to say, but will leave less chatty players in an eleventh-hour scramble to hunt down all of the “friendable” characters for one last sidequest blitz before the endgame.

The game’s emphasis on character interaction is reflected in its general world map design, with expansive, labyrinthine cities that dwarf its small and straightforward wilderness areas and dungeons. Take the first city and its adjacent field area, for example: The battlefields outside the dome are roughly four screens large, and, unlike many of the later areas, are not connected to the rest of the map. As for the first city itself? Here’s a minimalist map of it:

The game contains four more cities just like this. The early portions of the game in particular are spent almost entirely indoors, making for a low-octane start without much emphasis on action. It differs from the hour-long intro cutscenes of the rest of its genre in that the player is in control through almost all of it, leaving them to get hopelessly lost at their leisure. The slow beginning and initial lack of direction will be immediately off-putting to some players, but others will enjoy the ability to simply explore and to get to know the game at their own pace. The game does pick up, and at around the halfway point, it becomes more traditional, with a more open overworld and a greater emphasis on fighting – at least, until the final rush to befriend everyone in order to take on the final dungeon.

But once the combat does come, what is it like? Tizians such as Opoona have two tools available to them in battle: their bonbons, which are the floating balls above their heads (or where their feet would be, in Copoona’s case), and special powers called Force. However, in order to use these powers, Tizians must make use of a special hormone, and their body can generally only handle the pressure for around two minutes. This places an immediate time limit on battles, exceeding which counts as a KO. To keep up with this stringent time limit, the game’s main method of attack is similarly fast-paced: Basic melee moves are performed by tilting and releasing the control stick. Depending on the direction the player presses, Opoona and company will throw their bonbons in different arcs. To target specific enemies on the field, the player will need to throw trick shots that hook towards them, and players can target their weak points and avoid their shields by throwing bonbons such that they curve towards the enemy. The player can even hold down the control stick for longer and release it later to charge their shot for more power. But charging requires Energy, and after attacking, each character must wait for their squarish Energy Meter to refill before attacking again. It’s not quite a real-time battle system, since the characters are rooted firmly in place and only their bonbons move, but neither is it turn-based: Enemies will attack no matter what the player is doing, and the game requires awareness of their placement in space.

The magic system, Force, isn’t quite as elegant (yes, there are menus involved, and the game doesn’t pause when the player flips through them). But it often requires the same amount of consideration for space, since many Force spells have unique areas of effect. Skills can target specific levels of foes (airborne or ground-bound), or zigzag through the crowds, or crush closely-clumped groups of enemies. And while there are numerous spells that target everything on the field, later battlefields litter the floor with bombs that will explode if touched. Utilize one of these powerful skills, and it’ll detonate the bombs and knock off huge chunks of Opoona and company’s health. Like most RPGs, there is also some elemental voodoo going on, and magic does come with elemental affinities like fire, lightning, and earth. But enemies are also capable of resisting (or being vulnerable to) certain skills less out of element and more out of flavor: For example, little sister Poleena can learn a skill which floods the battlefield with stars, which does exactly 130 damage to all enemies… Except to an enemy known as the Star Human, whose celestial heritage gives them near-immunity to that one specific spell. Although logical, its specificity makes it somewhat unexpected in a genre known for more broad-strokes systems of strengths and weaknesses, such as “water beats fire.”

Items are one of the more oft-overlooked aspects of RPG battles-aside from the all-important, stat-raising equipment, many items’ effects have corresponding spells that can be more easily (and repeatedly) cast, and it’s often cheaper to spend a night at the inn to recover MP than it is to stock up on potions. Opoona attempts to entice players towards its inventory not simply by making them valuable, but by making them quirky. Among the most useful items in the early game, before Opoona finds his siblings and must take on parties of up to eight enemies all by his lonesome, are the packs of gum he can purchase from vending machines: They let him spit needles, cause explosions, and float like a balloon (no wonder the item descriptions tell him not to chew indoors). Healing items are foodstuffs like BLTs and minestrone, but other high-grade cures include pies stuffed with fortunes (like fortune cookies, but with fruit filling) and pizzas decorated to resemble roulette wheels. In-battle attack items generally have no spell counterparts and have unique animations, such as burying the battlefield in Tetris block look-alikes or swarming enemies with stickmen – with the ultimate battle item (and most powerful attack in the game) being nothing less than an avalanche of popcorn. This strangeness extends to the equipment, almost all of which visually affects each character’s bonbon in some way. Standard equipment will simply make the bonbons appear larger or shinier, but special items can wreath them in flames, or turn them into maces, or even surround them with tiny UFOs. It gives the items a distinct personality beyond their effects or the stats they boost, and helps each one be memorable.

But even in its more pugilistic later stages, the game still remains deeply entwined with its people. Opoona and his siblings have a raft of battle stats like most RPG protagonists, but they also have stats with names like Fame, Love, and Integrity. These storyline stats won’t grow just by fighting in battles and leveling up. Only by talking to people and making friends can one make these stats increase. Even for those bloodthirsty types most interested in battling, the game tempts players with promises of unique equipment and rewards should they follow it down the chatterbox path. “Just befriend enough celebrities to get a high Fame. Then you can act in a commercial and receive one of the rarest pieces of equipment!” “Just talk to this guy a couple times, and he’ll tell you where to find a rare rogue so you can complete your Rogue Book!” “If you only had higher Integrity, this shopkeeper would sell you better items!” Even aside from needing enough close friends to enter the final dungeon, much of the player’s success in the game is dependent on how closely he or she manages to integrate with the people of Landroll. The best battle items are hidden away with nondescript NPCs whom only the most ardently social will find. Stat-boosting opportunities come from befriending certain people and receiving free (or cheap) stat items from them. Even staying in a ritzy hotel offers excellent free goodies via the continental breakfast. Opoona never lets up on its point that it’s the people who really matter.

A player with guns blazing can zoom through Opoona‘s main game in around 40 hours, but Opoona was not a game truly designed to be zoomed through. Although the game can be played with a Wii Remote and Nunchuck duo, or the Classic Controller, the original control scheme for the game–and the one considered by the developers to be the “definitive” control–uses nothing more than the Nunchuck itself, allowing for a relaxed, one-handed play style. They envisioned a game that would appeal to whole families, adults and children alike, with worlds of optional content for players to explore at their own pace. Opoona begins the game on vacation, and in a sense, that’s what the game is most like: A vacation. If you just run through a vacation, spending half an hour at each landmark before moving on to the next, you won’t get much out of it. You might have a few pictures, but where are the stories to tell? What details will you remember from each place you visited? But if you meander from place to place, taking in all the sights and taking the time to learn about them, you’ll have a vivid experience that will stick with you for a long time coming. Hence why Opoona sometimes moves slowly. Completed in full, the game can take around 90-100 hours. That’s a long vacation.

Now, let’s talk about art and aesthetics.

Not musty old pictures on the wall; not a bunch of people in clothes worth more than a week’s wages sitting around and talking about the intent So-And-So Dead White Guy had when he made that brush stroke up in the left corner of the canvass. A thing which somebody made, and when someone looks at it, it sucker-punches their chest with that strange, trembling, enraptured feeling we identify as “beauty.” The emotions that well up inside of someone when they stare at those brush strokes, or that photosensitive paper, or that twisted lump of metal. Taking something that only exists in the space of one’s head, and making it something real with paper or plaster or pixels. Stuffing the vast expanse of one’s soul into a three foot canvas or three hundred pages, and wishing and hoping that someone else will someday look upon it and see perhaps one percent of one percent of the essence of them. Art.

Opoona is a game that has a deep, sensuous relationship with art. Every major city in Opoona has some kind of museum in it, and they’re one of the first places the player will find themselves visiting on their first tour through a dome. One of the biggest sidequests in the game is devoted to cataloguing all the art installments on Landroll in one easy-to-read book. There’s an entire city, Artiela, dedicated to the concept of art. Even the development team behind the game is named “Arte Piazza”–“art square” in Italian. Everywhere the player goes in the game, there’s some reminder that the developers were great art lovers.

For the game’s visual style, the developers deliberately averted the dark, realistic look favored by other modern games-somewhat ironically, they felt that look was too “gamer” and niche, and they wanted to appeal to a wider crowd. Opoona‘s models are smooth and colorful, and utilize a sort of cel-shaded look: The grapics lack the hard shadows found in a lot of cel-shaded games, but they do have the characteristic “outlining” often used in the style. The animations of the people and characters are, in a word, gorgeous. The studio used motion capture to animate the humans, and they move with impressive fluidity. They walk, talk, and even dance with realistic purpose and a silky-smooth framerate. (Even the choreography of those dances is surprisingly professional.) The rogues, on the other hand, have impressive cartoony motions that nicely display each monster’s individual personality. Each outdoor area is lushly populated with plant life and interesting rock formations and expansive backgrounds that, while unexplorable, set a breathtaking scene, be they towering trees as big as mountains, sparkling rivers cutting blue-gray gorges out of the rock, thick, looming storm clouds, lanced with brilliant light and circling rainbows, or soft, swirling dunes of sapphire sand. Even in the domes, the game’s urban areas boast a visual style inspired by modern architecture, and were designed specifically to hit the sweet spot between real and imaginary. Thus, there are places like Lifeborn’s majestic aquarium, where alien fish swim in hovering tanks just above Opoona’s head.

The generic human citizens of Landroll are done in a vaguely anime-esque style that doesn’t push any limits, though the fashions and hairstyles of those NPCs are off-kilter even by anime standards. But it’s in the alien species and enemies that the game flaunts its creativity. Few of the creatures resemble anything found on Earth, to the point of being difficult to describe in writing. The design for Opoona himself apparently came to character designer Shintaro Mojima in a dream, and he drew it in the steam on his bathroom mirror after a shower, so he wouldn’t forget it. The literal rogue’s gallery goes a step further by openly defying the enemy conventions in almost every RPG since Dragon Quest. The game’s first “traditional” enemy is also its last: The generic Jelly that assaults players in the beginning area. But even that goes beyond the usual “blob of goo” design and resembles a sort of slug entombed in a gelatin mold. Rather than animals and plants, Mojima drew inspiration from industry and machines for the rogues’ designs, giving them a unique blocky and tubular look. Even the enemies with familiar names, like “Golem,” “Dragon,” and “Vampire,” have designs created from whole cloth. The only real shame is the game’s reliance on palette swaps to fill out its bestiary.

But visuals are only one part of a game’s aesthetic feel; music plays a critical role in establishing the mood of a game. Being artistic people, the dev team doubtless wanted a soundtrack that matched the feel of the sort of game they wanted to make. To that end, the developers worked with Basiscape: an independent sound design company whose members had worked on such games as the Final Fantasy Tactics series, the Ogre Battle series, and the cult classics Grim Grimoire and Odin Sphere. The soundtrack they assembled was designed to match the main character’s worldview as he progresses through the game. It’s quirky, peppy, and good-natured; it has the welcoming warmth of a cartoon or a children’s movie, just like the cute face of its main character. Yet there’s a ballet-like gracefulness to it that lends the game an air of gravitas.

Most of the tunes in the game are upbeat and major-key. They have a jovial, bouncy feel to them, and there are many recurring melodies throughout the game that identify specific regions or moods. The main Opoona theme is a spry little tune that pops up throughout the game, usually during important moments. Each of the domes has its own theme, and most of the music in or around that dome is a variation on that theme. The game’s final major melody also defies the cheerful atmosphere of the others: “Spirit Poem” is a slow, reverent tune that plays when the game becomes more mystical and magical, and during moments of great emotion. In terms of instrumentation, the game blends synths with traditional orchestral instruments. Usually, the harmony and backbeat is provided by the synth, with strings and woodwinds carrying the main melody. It goes well with the game’s visuals, blending natural and futuristic elements just like the world and its creatures. The orchestral portions are also extremely performance-driven. They feature frequent grace notes, and slow, sliding portions that glide from one tone to the next to give a floaty, atmospheric feel. Real performances mean real emotion, and those emotions help bring to life head composer Hitoshi Sakimoto’s vision of a soundtrack that molds itself around the main character, emphasizing his feelings about his journey and creating sympathy for him in the audience.

But Opoona‘s true love of art is found not in its visuals or its music, but in its museums. Many games before it have flirted with the concept of in-game museums–these typically consist of fifty-pixel textures stretched out over two-hundred-pixel space, with a small examinable plaque beneath that explains the painting’s title and with it some description on what it’s supposed to mean to the player. In Opoona, in the city of Artiela, nearly every house in the dome has canvasses propped up against it, depicting strange cartoonish monsters or abstract trees or mysterious crow silhouettes against blazing orange backgrounds. And those are the throwaways; the artworks it doesn’t bother to explain. There are fifty-two “real” works of art scattered throughout the game, paintings and sculptures and even artistic installations, each of which has a solid page of description that details its name, the Landrollian year it was made, the school of artistic thought it represents, and the history of the piece. And while some of them do take the “slightly blurry texture” route (particularly, a group of landscape “paintings” based on in-game areas), for the most part, they are designed with the same care one would expect from a real artist putting that one percent of one percent of their soul into something. More than just artists, the real-life creators of these pieces were actors, adhering to fictional artistic styles and mindsets with such strength that their “fictional” works of art hold real conviction–and real beauty. Above it all, many of the game’s artworks are genuinely pleasing to look at; even hypnotic in some cases. In a way, their existence is representative of the game as a whole: Aesthetically pleasing, deeper than they appear on the surface, and most rewarding to those who take the time to get to know them.

Opoona‘s emphasis on socializing over action was always going to make it an acquired taste, but there is, sadly, one element in the English version of the game that holds it back even further in this department: The translation. By all accounts, the Japanese script of the game is lovely. There are glimmers of this in the English translation, with a few, almost poetic-sounding lines tucked away in strange, hidden places, and wry observations from the mouths of NPCs or in the game’s descriptive text. But for the most part, the game was nowhere near as well-translated as it could have (or should have) been, with numerous spelling errors, character name flip-flops, grammatical blunders, and whole clues rendered useless due to what appears to be thesaurus abuse. It’s readable, certainly. It’s generally a step above the old NES game translations. But even at its best, it tends to be stilted and unnatural-sounding. For a game that places so much emphasis on text, this is downright self-destructive. If being poorly-written prevents the player from enjoying or understanding such a major aspect of the game, they’re going to have trouble getting into the game as a whole. Perhaps, given the game’s poor showing in Japan, Koei, the publisher, lost faith in its abilities overseas, and simply rushed out a translation to fill a quota. Were Opoona given a better English script, it might have found a bigger following.

Eloquent or Engrish, however, Opoona still has something few other games can boast, at least to the extent Opoonadoes: A wholly unique atmosphere that’s all its own. ArtePiazza wanted to craft a game that would appeal to everyone: Adult and child, gamer and non-gamer. In doing so, they put their whole heart into creating a fleshed-out world not quite like anything else. Opoona is often compared to EarthBound: They’re both traditional RPGs with nontraditional settings, with extra helpings of love and care gone into making them fully realized worlds with flaunt-worthy style. Neither was a critical darling at the time of their release (Opoona sits at a middling 65 percent on Metacritic), but those who love them do so with hearts full to bursting. Maybe in fifteen years, it’ll have built up the same kind of massive cult fanbase, and the large-scale online petitions and fan campaigns will wring a sequel out of ArtePiazza. (The game does leave a number of questions unanswered, after all, particularly about that meteor.) In the meantime, the game itself provides enough content for at least two or three smaller games – if only Opoona, and the player controlling him, stop to find it.

Links:

Opoona Official Japanese Website.

Opoona English Teaser Site.

ArtePiazza Developer’s website.

Basiscape’s Website

Landroll Admin Center a fan-site with numerous guides and images (source of Tokione map)

Q&A with Opoona Developers and Character Designers

Interview with ArtePiazza

Interview with Basiscape