Content Warning: This article discusses child abuse and alcoholism

Gaming is an interesting medium. Thanks to its interactive nature, you can convey a lot just through the act of play and engaging players with the mechanics and systems. We’re starting to see more and more experimenting with this concept as the years go on, but one thing we’re still having trouble dealing with is how we use this unique aspect of engagement with games to explore more complicated and heavy subject matter. Most indie releases that do this use visual novel or exploration game formats, such as Will O’Neill’s Little Red Lie or the infamous Gone Home, but some do try to use traditional mechanics. This is the case for Papo & Yo, a puzzle platformer about dealing with an abusive parent as a child. That doesn’t sound like a combination that would work, yet it does.

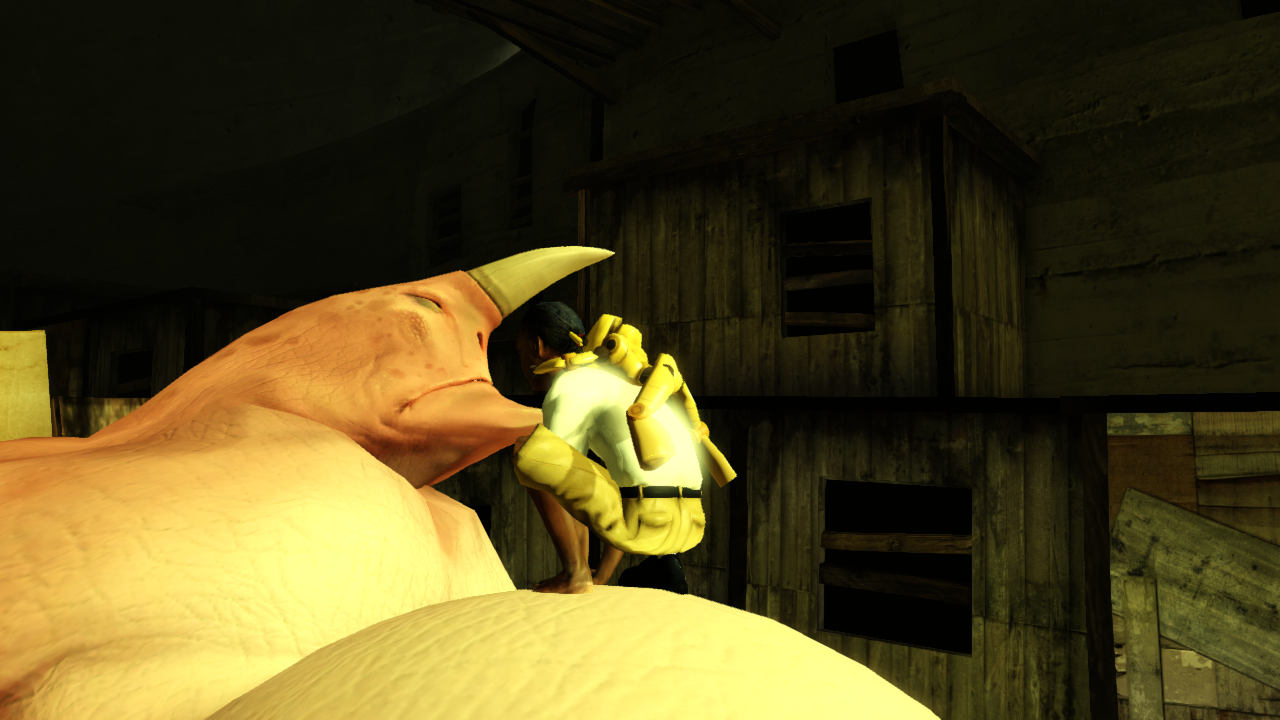

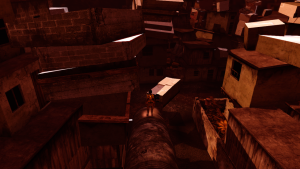

The game was the brain child of Vander Caballero, based on his real life experiences of living with an abusive, alcoholic father. It follows a young boy named Quico, who is hiding from something in a closet before a mysterious symbol on the wall opens a portal to a strange favela somewhere. He meets a girl with magical chalk who calls him cursed, along with a monster that stupidly lumbers around to eat fruit. That monster, however, has a violent side that comes out when it eats frogs, making it light aflame and attack whatever is near it. The girl says the monster can be saved of its rage by taking it to a shaman. Thus, Quico sets out on a journey with his robot companion Lula to cure the monster from its deadly true nature. Needless to say, things don’t go neatly or nicely.

Papo & Yo reads like a message from an adult Caballero to his younger self, and it’s far more insightful into the subject matter than most popular media. The common narrative with abusive relationships is that the violent party is forgiven or finds redemption, but that’s not how this usually goes in real life, especially with addiction at the center of the issue. As someone who deals with addiction issues and has been around people struggling with the same problems, I understand that it’s a condition that can’t simply be cured. It’s a demon on our shoulders that never really leaves, so the idea that the monster can be cured of its frog induced rage (the father of his alcoholism) is absurd – and the game knows it. They’re far too off the deep end, and the amount of pain we discover and see caused to Quico makes the ending message of the game all the stronger.

The game’s mechanics serve an important purpose in this message and narrative, as they’re meant to make you emotionally connect with Quico’s viewpoint. The thing about the monster is that it isn’t pure evil or hates you, not at all. It fact, through most of the game, it’s a gentle giant who laughs and plays a bit when you kick a soccer ball at it. Living with an abusive person isn’t hitting and screaming 24/7, especially when dealing with an alcoholic. There are good times, those times that convince someone to stay and think they can fix said person, but it’s not the victim’s place to “save” their abuser. Quico is a scared, confused child, he isn’t equipped to figure out how to help the monster, nor has any sort of authority over it. Despite all those fun times with the beast (further pushed by making the monster necessary to solve puzzles), it’s not enough to try and stay with or save the creature. Sometimes, the best decision you can make is to save yourself.

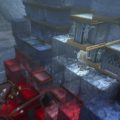

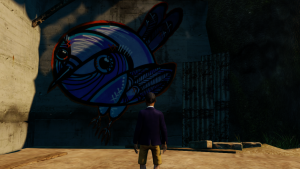

Puzzle platforming was a great angle to tackle this sort of relationship, as there’s a lot of down time where you can just relax and absorb a moment where you try to figure out a solution. You get a feel for who the monster is and why someone would want to hang out with it, especially in one puzzle where it can save you from death if you screw up. The world around you can be manipulated with chalk drawings the girl has left around, which can be as simple as pulling a switch or device to picking up a block and using it to control entire buildings. While few of these puzzles are difficult or challenging, their ease serves the narrative better by putting you in a more relaxed state, though there are stumbling points. A segment with a house bridge fails to show you can move the bridge side to side because the chalk lever it uses is usually associated with back and forth movements only, for example. A late game bridge puzzle also proves frustrating of you don’t remember you can splatter frogs on walls, which was only used for one other puzzle up to this point.

The game has some fantastic art direction, using the favela setting to its fullest. Through the eyes of a child’s imagination, the square and simple buildings become possible blocks and platforms you can manipulate to your advantage, and you slowly start to see the realistic presentation peel away and reveal a pure white, blocky underbelly. Brian D’Oliveira’s score is also brilliantly interrogated into gameplay, slowly revealing more of his melodies as you get further and further in a puzzle, really standing out in the house bridge puzzle. Its a good thing the game has such a sense of style, because it is not a looker on he technical side, especially with the wooden and often expressionless character models. Serious story beats lose their edge a bit at points partly because of this, or partly because there’s a scene missing (like Quico not reacting after a massive, game changing moment towards the game’s end). The PS3 version was especially notorious for technical jank and glitches, though the computer ports seem to have patched a lot of this out.

While the game lacks a lot of polish, it’s incredibly memorable for its ambitious story and just how well it manages to convey everything in a two hour time frame. Papo & Yo is one of those games that really shows the possibilities of the medium, and while there’s debate to how much it succeeds at what it aims to do, it certainly shows that you can apply the unique qualities of games to create a story in a way other mediums can’t. It’s an indie darling for a reason. Though ending by teasing that you can collect hats by replaying the game over and over does take some wind out of the sails.