Phantasy Star was a hit, and it wasn’t long before work started on a sequel. It was originally conceived as a Master System game, but with Sega pulling the plug on the system in Japan at the end of 1988 and the advent of the Mega Drive that year, the decision was made to move to the more powerful console. With the jump to 16-bit, the team got larger; newcomers included character designer Toru Yoshida and assistant director Hiroto Saeki. Kotaro Hayashida was still involved, but he did not lead the project, probably to focus on other early Mega Drive titles like Space Harrier II and Alex Kidd in the Enchanted Castle, so the role was filled by Chieko Aoki, who’d created the initial outline for Phantasy Star and would also serve as the main writer this time around. The Japanese subtitle, Kaerazaru Toki no Owari ni, translates to “At the End of the Time We Cannot Return To”.

Close to a thousand years have passed since the fall of Lassic and Dark Force. For centuries, an autonomous computer network known as Mother Brain has been regulating all aspects of the environment in the Algo system, and Mota (or Motavia) is now a green planet, similar to Parma. But this utopia (at least for Parmanians) is threatening to fall apart. Two years earlier, an accident at the bio-systems lab resulted in the birth of a creature hostile to humans. The lab was shut down, but before long, similar creatures spread throughout the land, threatening the population. A class of mercenaries known as Hunters rose to fight those “bio-monsters”, but some of them turned to preying on the people instead.

After centuries of complete dependency on Mother Brain, the Government, or what’s left of it, has come to defer to it as a Godly figure (or more obviously, as a mother to a child), and is reluctant to question its omnipotence. And even if it wanted to, no one knows where Mother Brain actually is, or how to access it.

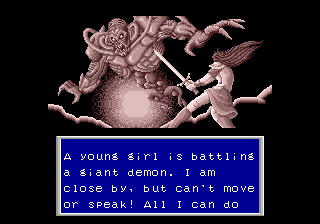

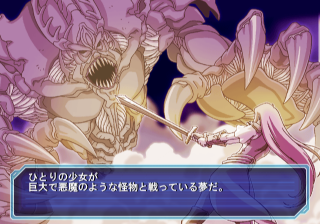

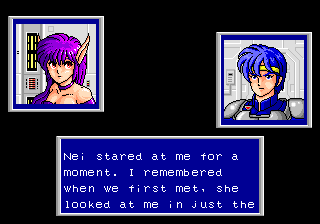

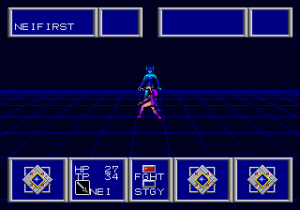

For Rolf, a government agent in the Motavian capital Paseo, the last few months have been tumultuous. He has taken in a mutant girl, Nei, born of experiments between human and bio-monster genes, after saving her from an angry mob. Her mutant genes have caused her to grow from a child to a woman in a matter of months, and he has come to see her as a younger sister. He has also been haunted by a recurring nightmare, in which another young woman, whom we recognize as Alis Landale, is desperately trying to fend off the attacks of some great demon, as he watches, powerless to help.

The game begins as Motavia’s Commander, no longer able to sit back while things deteriorate, sends him out on an important mission; get to the Bio-Systems Lab and recover the Recorder, where all data concerning the lab’s activity is stored, so as to figure out why these monsters continue to be produced. Nei insists on tagging on; though Rolf is initially reluctant, he finally agrees.

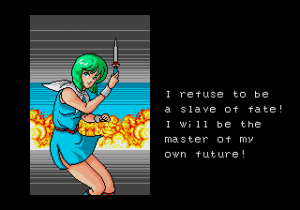

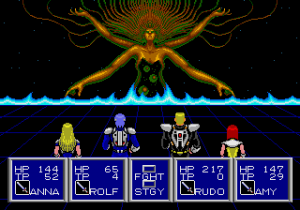

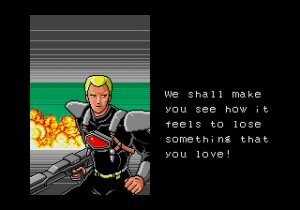

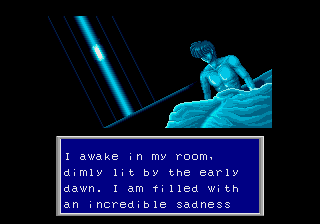

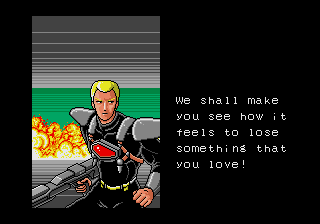

Their journey will be a tragic one. Phantasy Star II boasted the biggest cartridge for a console RPG upon its release – 6 megabits versus its predecessor’s 4 – allowing it to develop its story a bit further, and it is strikingly downbeat. In one sub-quest, a man murders his masked daughter before killing himself when he realizes who she is. Later, the heroes become fugitives, fleeing a death sentence. An entire planet is destroyed. It has one of the very first dramatic death of a playable character in the genre, and one of the great shock endings in the entire medium.

A spoiler-free excerpt from the ending

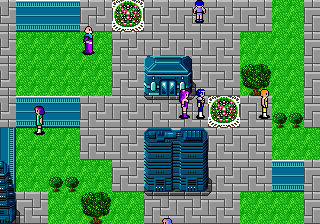

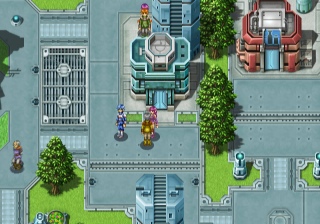

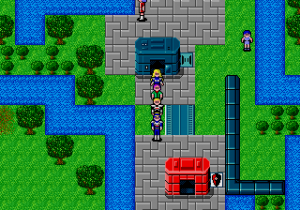

You would never guess so from its aesthetics, however. The sprites and environments are lively and colorful, and Tokuhiko Uwabo’s soundtrack is almost always upbeat and uptempo, projecting a vibe of futuristic optimism contrasting with the events of the game. The tone is a bit more stern on Dezo, with a nostalgic overworld theme and a mixture of melancholy and hard beats in the towns and dungeons. Whether or not it fits, the music is generally excellent, and sounds like very few RPGs, with deep basslines, pounding drums, and memorable melodies. The closest thing to it in spirit, if not in quality, is probably Space Harrier II‘s soundtrack, scored by the same composer a few months earlier.

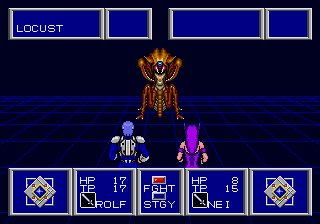

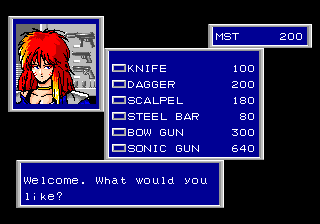

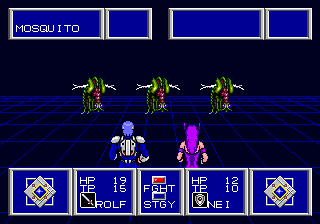

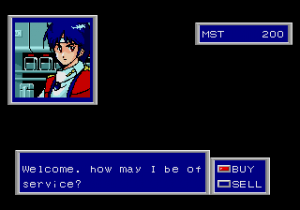

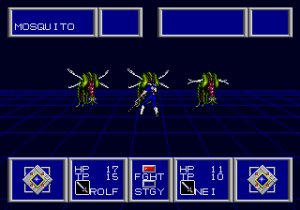

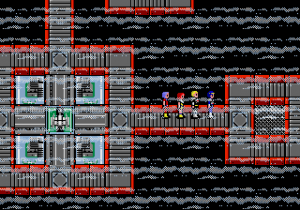

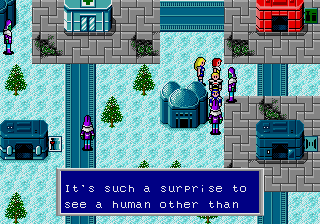

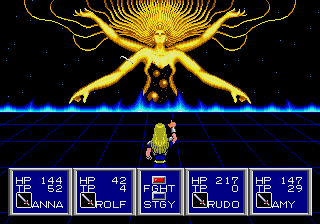

The graphics, too, are far beyond those of the Famicom RPGs that dominated the market at the time, or even the first handful of PC Engine RPGs, which tended to look like Famicom games with more colors. The improvements, however, came with some trade-offs. The towns are bigger, but you cannot enter houses, only shops. The impressive full-screen portraits of NPCs are gone, but major characters and shopkeepers get a smaller one, drawn in a more detailed, anime-influenced style. Enemies are still animated, but the camera is now set behind your characters, and you get to see them actually attack as well. When equipped with melee weapons, you see them appear before the enemies, swiping at them, which looked especially impressive at the time. The elaborate battle backgrounds are out, however, replaced by a sort of futuristic grid which makes it look like you’re fighting in an ’80s idea of cyberspace. The art style, both in and out of battle, still edges towards realistic proportions for people, if not for buildings.

Natural backgrounds or not, the battles are darkly stylish.

Outside of its big moments, the game is still very much an ’80s RPG, full of grinding and sparse on plot developments. Enemies get drastically stronger from one area to the next, and equipment is expensive, necessitating a lot of fighting to keep up. Boss battles are rare. Even as the genre as a whole was starting to turn towards a town-dungeon-town formula, Phantasy Star II has twice as many dungeons as it has towns. On the plus side, these are crawling with people, who provide plenty of background on their world and its history. With food and necessities provided for, many of them just laze about, relying entirely on Mother Brain.

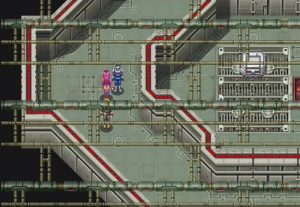

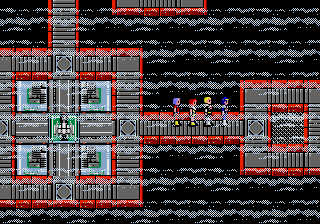

Though the developers initially planned to bring back the first-person dungeons, they eventually opted to go with an overhead view, for a variety of technical reasons. Phantasy Star II‘s dungeons are exceptionally large and complex, with the very first one in the game featuring four floors and teleporters. The encounter rate may be slightly lower than its prequel’s, but it’s still high, turning each dungeon into a war of attrition. According to an interview included in the 1993 World of Phantasy Star fanbook, they were drawn by an overzealous new employee, and though the team had mixed feelings, director Aoki decided to keep them so his painstaking work wouldn’t go to waste. They’re so hardcore that Sega thought it necessary to package a free, 110-pages hintbook with the game in Western territories, containing maps for all of them. If you opt not to use it, you may find yourself having to make several expeditions per dungeon – first to figure out the layout and grab the treasure, then again to actually finish it. This method also has the advantage of giving you enough battles to fight that you don’t have to grind outside afterward.

The dungeons also show off some parallax scrolling by sticking in pipes and other things directly below the player’s view. These look neat, but sometimes block part of the view, contributing to the feeling of disorientation.

The battle system is a bit different from before. It now allows for multiple enemy types to fight side-by-side, but you’re still limited to targeting groups rather than individual monsters. The main menu offers two options, Fight and Order. Order lets you assign specific actions to characters, while Fight lets those actions repeat, turn after turn, until you press a button to gain access to the menu at the term of the current turn. If you don’t give them orders, characters attack, though new characters are usually set to block when they first join you. Another innovation is that you may now equip weapons or shields for each hand, allowing certain characters to attack twice per turn or boosting their defense.

You can no longer save everywhere, at least not by default; instead, you must record your memories in data centers found in towns. Teleport Stations now allow you to travel to any town you’ve visited before. This convenient means of transportation has rendered vehicles obsolete within the game’s universe, and only a version of the Hoverbike/Hydrofoil remains from the trio of vehicles in the first game (the Jet Scooter).

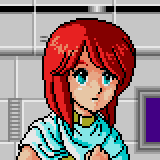

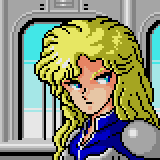

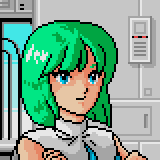

Churches have been replaced by Cloning Labs, where dead characters can be “revived”. Rolf has a home of his own in Paseo, and as you visit new towns, character who’ve heard of your deeds show up back at your house, where they tell you a bit about themselves and ask to join you, then remain mute up until the ending. The roster includes eight characters, but the party can only accommodate four. Joining Rolf and Nei are Rudo, a former soldier turned Hunter after the death of his family at the hands of Biomonsters, specializing in large firearms; Amy, a young doctor with great healing powers; Hugh, a Biologist who takes on Biomonsters with specialized techniques to protect weaker lifeforms; Anna, the tough counter-hunter (or Guardian in the localized script), who goes after Hunters who go rogue and uses slicers, which attack all enemies in a horizontal line; Kain, a failed mechanic who’s developed a specialty in wrecking mechanical enemies; and Shir, a bourgeois thief who steals for thrills. While weak in battle, she has the ability to steal items and equipment from stores just by entering and leaving them; her kleptomania is the only way to acquire the Visiphone, which lets you save anywhere.

Rudo

Amy

Hugh

Anna

Kain

Shir

Towards the end of the game, you meet up with an Esper (or wizard) named Lutz, who has remained alive for a very long time through cryogenics. In early drafts of the story, Lutz, or Noah in the English version of Phantasy Star, was considered as the lead character, but he does not join here, instead providing guidance as a wise elder figure.

Still looks young, though.

In general, the sequel’s translation sticks closer to the Japanese original’s naming conventions. The years are preceded by the acronym “A.W.” rather than “Space Century”, standard healing items are known as the “-mate” series – monomate, dimate, trimate – and spells like Fire or Wind become Foi and Zan. The names of most playable characters were still changed, mostly so they could fit inside the menus’ four-characters limit, which is how Motavia became Mota, for example. While the dialogue is still easy to follow, the syntax can get pretty stilted and goofy.

Other notable changes include an NPC, a music teacher probably modeled after Elton John, who was originally implied to be homosexual; his dialogue was changed so he doesn’t hit on the male characters anymore, though he still gives them cheaper lessons with no explanation. Perhaps he’s just sexist now?

The Japanese version also uses different, slightly sharper drum samples for the entire soundtrack, which were changed to softer ones for the Western version. As a result, the official soundtrack released in 2008 along with the Phantasy Star Complete Collection for the PlayStation 2 has both versions of the soundtrack in their entirety.

A fan re-translation was also released in the early days of ROMhacking, but while it might be a touch more accurate in some spots (and less in others – there’s a very dated Windows 3.1 joke right at the start), it reads even worse.

Phantasy Star II was a landmark title, especially in the West, where it predated even Final Fantasy in America by a full year. It was popular enough with the press that Video Games and Computer Entertainment deemed it the best title of 1989. In retrospect, however, the huge, maze-like dungeons are extraordinarily demanding, and it’s a bit sad that some of its prequel’s most impressive graphical flourishes have been dropped. It’s still a very stylish game with a great soundtrack, a great setting, and the skeleton of a great story. It’s just that it would probably be more enjoyable today if it had been made a few years later.

As with the first game, Phantasy Star II pops up on numerous compilations. On the Saturn Phantasy Star Collection, it’s basically identical to the original, but has the ability to increase the character’s walking speed, which greatly helps in the dungeons. As with the first game, only the Japanese version is playable.

On the Phantasy Star Collection for the Game Boy Advance, Phantasy Star II turns out better than its predecessor. Rather than squashing the entire screen display, the overhead segments are simply cropped, and all other UI elements are rearranged to accommodate the smaller screen. It is a little cramped, and the smaller view makes the dungeons even more frustrating to navigate. The GBA doesn’t support FM synth, so it uses an odd process that emulates the Genesis sound chip with samples. Despite some static, it works relatively well.

For the Phantasy Star Complete Collection on the PlayStation 2, again there’s the ability to increase walking speed, as well as tweaks to increase gold and experience gains to reduce grinding. Both the American and Japanese versions are included on this package, so you can compare both soundtracks.

Phantasy Star II, and the rest of the Genesis games, appear in the Sega Genesis Collection (PlayStation 2 and PlayStation Portable), Sonic’s Ultimate Genesis Collection (PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360), and Sega Genesis Classics (PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and Switch), plus it has appeared on iOS and Android mobile phones, and is downloadable on Steam. These are just straight emulations of the American ROM with no enhancements.

Phantasy Star Generation: 2 – PlayStation 2 (2005)

As with the first game, Phantasy Star II received a remake for the PlayStation 2 as part of the Sega Ages 2500 line. The graphics in this version, re-titled Phantasy Star generation:2, have been redone in the same 2D high res style as the first revamp, with the same pros and cons – some of the sprite art isn’t bad, but the character designs are inconsistent in quality. Nei, in particular, with her gigantic ears and frilly outfit, is the worst of them. The spartan blue grid for the battle backgrounds from the Genesis game have been replaced by actual backgrounds this time, although you can still use the grid if you’d like. Some of the dialogue has been expanded, and there’s an extra subplot regarding a missing government agent named Shelly.

The battle system has been slightly upgraded to allow manual targeting of enemies, although there’s still the Auto battle function. There are now three levels of attack, determined by how long you hold down the button – higher level attacks do more damage but are more likely to miss. You can also block attacks by timing button presses right before an enemy hits. Also included are limit break style special moves exclusive to each character that build up as your party takes damage. You’re graded on performance after each battle, which determines experience points bonuses. Characters not in the active party will still gain some experience points, or craft random items for you.

Many of the other additions have carried over as well, including the ability to talk among party members, the elemental affinities, the faster walking speed, a larger inventory, TP restoratives, and mid-dungeon saves. There’s none of the extra fetch questing from Generation: 1, and the difficulty here is much closer to the original, if not harder – which is to say, extremely brutal. The dungeons are mostly the same, with some changes here and there. The arranged music is slightly better than in the first remake, but still not quite as faithful in tone as it should be.

Additionally, Phantasy Star II was notable because a pretty major player character is killed partway through the game, long before anyone had ever heard of Aeris. This remake fulfills all kind of fanboy fantasies by allowing you to resurrect them – but only if you have a completed save from the first Phantasy Star remake, and go through a long process of tedious steps. Finally, if you’d rather not bother with the remake, Sega included an emulated version of the original Mega Drive game…though since it also appears in the later Phantasy Star Complete Collection, also on the PlayStation 2, it’s probably not necessary.

Comparison Screenshots

Links & Sources –

Shmuplations – 1993 Developer Interview

Mobygames – Game credits.

Segaretro.org – Has scans of the hintbook packaged with the game.