Every company has their oddballs and one-offs that get eclipsed by their bigger franchises. Urban Champion is more or less forgotten by Nintendo (likely for the better), Capcom will make no sequels to The Speed Rumbler, and where’s Axelay 2, Konami?! Whether they deserved sequels or not, some games just peter out into obscurity. Namco was slightly better about this than other companies, if not just for their amazing Namco Museum compilations of the nineties. While featuring the expected big ones like Pac-Man, Galaga, Mappy, and Dig Dug, each installment would have at least one really weird game that no one would ever expect to see. 1 had Toypop, 2 had Grobda, 4 had the Genji and Heike Clans (Genpei Toumaden), and 5 had Baraduke. Today’s lesson is on 3‘s obscurity, a science-based action-puzzler named Phozon. It had oddly never seen actual release outside of Japan until its appearance on Namco Museum, making its appearance alongside Ms. Pac Man and Dig Dug rather jarring. While certainly not as notable as either or those games, Phozon nonetheless deserves a play for its unique premise that can’t really be compared to any other game of the time.

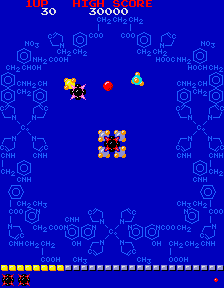

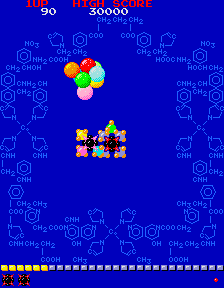

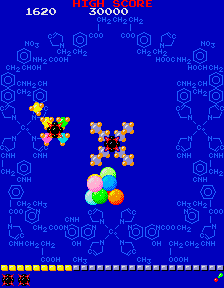

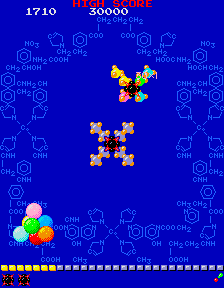

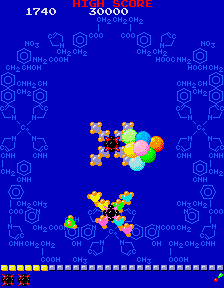

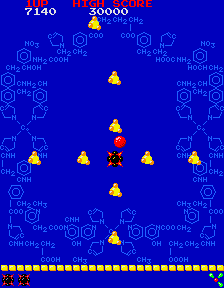

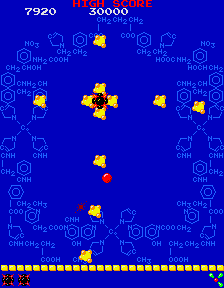

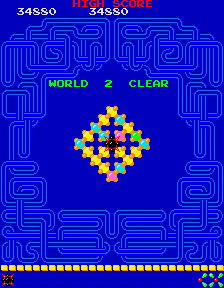

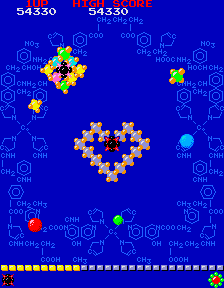

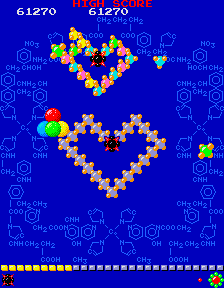

The playfield is a large blue screen with either various molecular formulas strewn about or one long elaborate line around the perimeter. The former background implies that your goal is to make some sort of chemical compound, though this game probably isn’t very effective at teaching the scientific method to grade schoolers. Your avatar is titled Chemic, a black atom with red spikes protruding from its corners, which is pretty badass for a subatomic particle. The dead center of the screen shows a duplicate of chemic with thingies attached to it in a specific pattern. These “thingies” are facsimiles of Moleks, molecules that are able to bond with Chemic simply by floating into them. Your goal for each level is to guide Chemic so Moleks stick on it in the exact same pattern shown in the center. The Moleks are always moving and it’s likely you’ll approach one from the wrong angle, and you won’t win if you have even one extra Molek disrupting the pattern. That’s why there’s an eject button that allows you to shuck off the last Molek attached to you, and you will be making fair use of this button. After beating the first stage, the second stage has you keep your previous Molek pattern and requires you to add even more on top of it, and even more so for the third level.

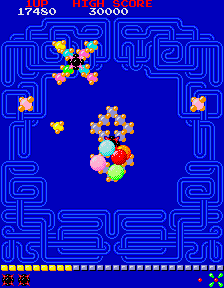

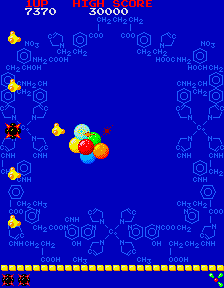

It’s tough enough to line up all Moleks the way you want, but you have to form the pattern while dealing with a rainbow-colored marauder. Your sole antagonist in the quest to become complete is Atomic, a large cluster of multicolored spherical molecules whose purpose is akin to the Qix from the eponymous Taito puzzle series. Atomic floats about in semi-random patterns and direct contact with Chemic loses a life. Besides just drifting about, Atomic has three tricks up its sleeve: It can disband all of its molecules as they each lurch outward for a second before reforming, it can shoot projectiles that can blow off your meticulously placed Moleks, or it can do the first move and have one of its individual globes burst into eight smaller projectiles, each of which can destroy a Molek as well.

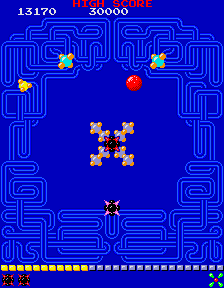

Normally, you have to avoid Atomic, but at the beginning of any stage where you still have Moleks attached to you, the Moleks spin rapidly and can actually grind away Atomic’s molecules if you position yourself just right. Most stages also have rapidly flashing Power Moleks that give you this temporary offensive power once they attach to you. Still, you’ll be trying to avoid Atomic for most of the time until you complete three patterns in a row. Every fourth level gives you the chance to exact sweet revenge on Atomic by giving Chemic the ability to fire damaging Moleks in four simultaneous directions, temporarily changing the game into a shoot-em-up. The bonus ends prematurely if you get hit, obviously, but you can destroy up to four Atomics if you’re savvy enough, granting a large perfect bonus. After a bonus level, you’re back to Chemic without any Moleks attached to it and will have to start off on a new pattern.

Phozon is a rather unorthodox premise that seems alien at first glance, but even without being able to understand the Japanese text that flashes up in the original arcade version (the version in Namco Museum Vol. 3 gets rid of the Japanese text), you can probably gather what to do simply by looking at the center diagram. It starts out simple enough but gets incredibly difficult by the third set of levels, where you basically have to completely eject your current pattern and start from scratch for the next one. Phozon definitely makes for a good challenge under a rather original science-themed setting. It may not have the timeless quality of Pac-Man, the frantic pace of Galaga, or even the catchy music of Mappy, but Namco considered it good enough to feature on their premier nineties compilation series, and its place is arguably justified. It even popped up many years later on iPhones as part of a “Namco Arcade” app, for whatever that’s worth. You probably won’t learn anything about the scientific method after playing Phozon, but you will have experienced one of Namco’s lesser-known sleeper hits.