- Planescape: Torment

- Toment: Tides of Numenera

Warning: this article contains major spoilers for Planescape: Torment, including references to the game’s ending.

The worlds(s) of Planescape

When any piece of fantasy fiction is compared to Dungeons & Dragons, it’s rarely a positive thing. Despite the influence and popularity of this famous pen and paper RPG, if a setting is described as ‘D&D-like’, you can expect it to be a generic fantasy story with races borrowed from Tolkien, an assortment of evil beasts, a few evil overlords with magical powers and a society that superficially resembles medieval Europe. Despite the perceived lack of originality, one of the game’s possible campaign settings is the strange and unique multiverse of Planescape.

Planescape could be described as a ‘meta-setting’: it combines all the other worlds of D&D (most – but not all – of them are different parts of the universe known as the Prime Material Plane), adds different universes for the Greek Pantheon, Valhalla, Christian demonology, the Divine Comedy, four classical elements and a few other things. The whole multiverse is a setting of conflict between order and chaos – its most extreme form is the eternal Blood War between two evil races: ‘lawful evil’ baatezu (devils) and ‘chaotic evil’ tanar’ri (demons). In the center of all this lies the neutral plane of Outlands, from which other universes can be accessed. In the center of Outlands stands an infinitely tall Spire, on the top of which floats the city of Sigil laid out on the inside of a torus. Sigil is the ‘City of Doors’: every door, window or arch is a portal leading to a different plane – as long as you have the right key. The city stays neutral in all major conflicts, but it is itself a battleground for different factions (inspired by those in Vampire: The Masquerade), closely watched by the mysterious Lady of Pain – both a ruler and a prisoner of Sigil.

Sigil is a fascinating city in both its architecture – which, in addition to the endless interdimensional portals, shifts and changes constantly as it is altered by the dabus, servants of the Lady who speak through images – and its culture (with faction politics, visitors from other worlds, a criminal underground with a unique dialect based on thieves’ cant and Cockney rhyming slang). It’s no less interesting outside of Sigil as the planes range from the fantasy worlds of the Prime Material Plane to the clockwork universe of Mechanus, inhabited by the robotic collective of the modrons.

The scope of this setting is of course far too big for a single video game – even moreso in the late 1990s, when Planescape: Torment was being developed. The huge multiverse consisting of dozens of infinitely large worlds, many of them working according to different rules and all of them with completely different landscapes and inhabitants, is just not something that can be practically realized in a non-tabletop setting where the potentially limitless imagination has to be reduced to fit the technical limits of gaming PCs – not to mention the workhours needed to create all the content. Thus, Planescape: Torment takes place mostly in Sigil. Visits to different planes are fairly short and usually focused on small areas: the city of Curst and a small desert section in Outlands, the same city in Carceri, an optional ‘dungeon simulator’ in Mechanus, two whole screens of helish Baator and the endgame on the Negative Material Plane. Most of the other planes will be mentioned in passing, while Limbo and the Elemental Plane of Fire are described in text-only retrospectives, which play important parts in the backstories of certain recruitable characters.

Despite the reduced scope, Planescape: Torment is still very much a Planescape game. Themes central to the setting – multiple worlds, Blood War, factions, gods – play important parts in the story of the game, even if the player doesn’t do as much ‘planeswalking’ as could be expected from the title. The focus on Sigil also pays off in that Planescape: Tormentreally captures the mysterious atmosphere of this place. The game’s world clearly doesn’t follow the standard rules of our reality – or the standard rules of fantasy for that matter. Even though is a strange place, there always seems to be some logic behind its strangeness – but the exact workings always evade your grasp. Planescape: Torment tosses you into a world where an alley can be pregnant, logical reasoning and strong will can remove people from existence and a shop specializing in curiosities from different worlds will try to sell you baby oil made from real babies – and it does so in a brilliant way so that it never feels like a pointless, random collection of things people would consider weird.

Infinity Engine and the late 1990s cRPG landscape

Planescape: Torment is powered by Bioware’s legendary Infinity Engine. As such, it’s played from an isometric perspective and employs a real time combat system with active pause. The main character is controlled directly with a mouse and the companions either the same way or by an adjustable (but not very good) party AI. The rules are a fairly accurate representation of second edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, which means that it has some interesting but nowadays unpopular mechanics like the need to memorize spells (which creates a natural restriction of how often the spellcasters can actually use their abilities) or the always controversial armor class and THAC0 stats.

As Planescape: Torment was the second game to use Infinity Engine after the original Baldur’s Gate, its version of the engine is still a bit clunky and unpolished when compared to Baldur’s Gate II. The most annoying of the problems is the need to pixel hunt for items dropped by enemies (or fallen party members), which are sometimes covered by terrain. The optional dithering of obstructive foregrounds can help but it can still be hard to see (Baldur’s Gate II solved the problem by allowing you to highlight interactable objects by pressing tab). The pathfinding is pretty weak – especially when fighting in tight, irregularly shaped streets and corridors – which in case of Planescape: Torment translates to ‘very often’. The game does a good job of reducing the need to navigate different menus during gameplay by introducing a ‘radial menu’ accessed by right clicking, which pauses the game and gives access to spells and ‘quick item slots’ but it’s a shame that unlike ‘quick items’, spells cannot be assigned to keyboard hotkeys.

Planescape: Torment might be an Infinity Engine game but it’s also clearly a Black Isle title, with an approach to quest design not dissimilar from that of the first two Fallout games. Almost all of the quests can be solved through dialog and stat checks (but no skill checks, as skills in the game are limited to identifying unknown items, weapon proficiencies for fighters and lockpicking, pickpocketing and stealth for thieves), without the need to enter combat. It’s a good thing too, because combat is clearly the weakest part of the game. Some of it has to do with the unfortunate mixture of level design and pathfinding but the fairly low equipment variety combined with the fact that many characters have plot-related equipment restrictions also contributes to the problem. Another contributing factor is that aside from magic (with uses limited by design), there aren’t too many ranged combat options – either for players or for enemies, which are more often than not simple melee trashmobs.

According to the game’s end credits, Planescape: Torment also takes inspiration from Final Fantasy VII and VIII. While combat systems, structure, quest design and non-linearity put the game squarely in ‘western RPG’ territory, the influence of Japanese games can be clearly seen in the lengthy animations of high level spells – not unlike Final Fantasy’ssummons. Console RPGs might also have influenced the NPCs with their memorable quirks and the fact that many of them have an optional sidequest attached to them to further their character development – a concept more fully realized in Baldur’s Gate II and later Bioware games which made those “character quests” an integral part of computer RPG experience.

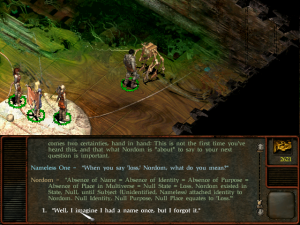

Null Identity, Null Purpose, Null Place, equates to ‘Loss‘

Unlike most other computer RPGs, Planescape: Torment doesn’t allow players to create their own characters. The game’s protagonist is always the Nameless One – an immortal amnesiac looking for the truth about his identity. It’s still a middle ground between creating a character and controlling a predefined one: while the Nameless One will always look the same and have the same backstory, his stats and personality (or, more specifically, the personality of the current incarnation) depend on the player. The game still gives many opportunities to roleplay and make decisions – both small (sometimes it’s possible to choose not only a dialog option but also intentions behind them: the other characters won’t notice the difference between an honest response and a lie, but it does carry a small alignment modifier) and fairly large – although mostly on a personal level: you won’t save the world or conquer it, but you may save different people or kill them, uplift or abuse, help or betray.

The question of identity is an important one: The Nameless One not only has to find his place in a strange, confusing world, but also deal with the consequences of his actions – often the ones he doesn’t remember (should he even be responsible for them? – that’s another of the game’s various dilemmas). The recruitable characters often struggle with their identities as well, although of a different kind: their backstories tend to include the idea of being different from or getting into conflict with those seemingly similar to them – usually members of their own race.

Also important are concepts of loss and regret. The Nameless One can complain about not being whole, about part of him being missing. This takes many forms: lost memories and identity (once again), the inevitable deterioration of his mind and body (despite immortality) and of course Transcendent One – literally a part of him that was separated when he became immortal. There’s a good reason for the game’s final location being called Fortress of Regrets.

The search for identity and the attempt to regain what was once lost is the main motivation for both the player and the Nameless One. The first thing you’re looking for in the game is the journal the protagonist has lost between his incarnations – and even though during the course of the game you’ll find a few different journals, none of them will give away too much about your past. Ultimately, the identity of the Nameless One from before the game begins is less important than that of the playable Nameless One – according to the design document from the time when the game was being developed under the working title Last Rites, this is how the character creation in Planescape: Torment works. The Nameless One is built primarily not by increasing and decreasing numbers in a menu, but through decisions and the natural interaction between the character and the game.

You wake up in The Mortuary

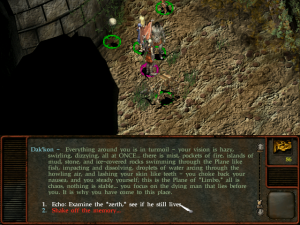

The plot of Planescape: Torment begins with the Nameless One awakening in The Mortuary – a giant morgue which serves as the headquarters of Dustment faction – a semi-religious organization founded on the idea that everyone is already dead and should seek to achieve ‘True Death’ by rejecting all earthly passions. From there, he emerges to ‘The Hive’ – poor and dangerous slums of Sigil inhabited by criminals, prostitutes, menial laborers, small-time merchants and ‘collectors’ – people who make a living by looking for corpses and selling them to Dustmen who turn them into zombies.

Then, the Nameless One’s quest will take him to several other parts of Sigil. First are the catacombs, which are inhabited by two unusual societies: the ‘Dead Nations’ where zombies, skeletons and ghouls are ruled by the reclusive Silent King (certain decisions can lead you to becoming his successor, which is one of the few ways to actually lose the game) and their sworn enemies, the collective consciousness of rats. Later he’ll explore the Lower Ward, where Sigil’s middle class lives among the machinations of rivalling factions and the poisonous air from portals to hellish plains, as well as Clerk Ward, home of the bored, decadent, often hedonistic and sometimes depraved (you can meet a woman who will give you money for the opportunity to kill you) aristocracy.

The locations outside of Sigil are less interesting, although they too have their memorable moments. The prison city of Curst, where liars and traitors live, works not unlike the world of Pagan in Ultima VIII – it’s a place where sometimes the only way to progress is by causing harm, one way or another. During a confrontation with the Pillar of Skulls in Baator – a grotesque, screaming creature made of the heads of those who gave others dishonest advise in their lifetime – the Nameless One must sacrifice something before getting the answers he needs. And there’s of course, the game’s finale in Fortress of Regrets.

On his journey, the Nameless One is accompanied by a colorful cast of recruitable characters, each with a fairly deep and interesting backstory. The number of possible companions is smaller than in Baldur’s Gate, but they’re also much more developed and memorable, with many possible interactions between each other and a few possible relationships with the player character. Neutral NPCs and major antagonists are no different, often having their own agenda and a sense of morality which, while often strange, usually goes beyond simply being evil for evil’s sake. The NPCs of Planescape: Torment add a lot of personality to the game, providing both humor (despite many darker themes, the game can often be quite funny) and emotionally resonant tragedy – the game’s more personal narrative means that an evil Nameless One lying to someone who trusts him can make the player feel far worse than an evil Vault Dweller or Bhaalspawn slaughtering dozens of innocent people (in Fallout and Baldur’s Gate, respectively).

Recruitable Characters

The Nameless One

The game’s immortal protagonist – a human whose plan to cheat death didn’t go the way he expected. He lived many lives and managed to become an expert of every possible skill – levelling up for him is just the matter of remembering how to do things. During his unimaginably long life he managed to antagonize every single god, which is the reason for his inability to become a priest. His experiences left his body horribly scarred, making him look more like a zombie than a man. Of his previous lives, two come back to haunt him more than others: the Paranoid Incarnation (a violent madman setting traps to destroy both his enemies and his future incarnations who ‘come to steal his body’) and the Practical Incarnation (a ruthless manipulator who set up complicated plans without regard for the feelings or lives of people around him).

Morte

The first NPC met during the game: a wisecracking, perverted floating skull who claims to be a mimir (‘a talking encyclopedia’). Serves primarily as a comic relief character, but as the game goes on, it becomes obvious that he’s not being completely honest with the Nameless One and that he knows more than he tells him. He can’t equip too many things due to the fact that it’s pretty hard to put a skull in a suit of armor – but even without one he has great defenses and serves as the typical tank (he even has a special ‘insult’ ability which causes its target to attack him in melee).

Dak’kon

A warrior mage (‘zerth’) of the strange race known as githzerai, who dwell in the chaotic world of Limbo, which they shape with their will. He wields the karach blade – a sword that changes shape according to the emotions of its owner. He religiously adhers to the words of Zerthimon – an ancient hero who freed the githzerai from their slavery – and has to deal with a crisis of faith. Another of his problems is that he was deceived into giving up his freedom – and freedom is one of the biggest githzerai virtues. Originally intended as a lawful member of a chaotic race (a paradox similar to that of other Planescape: Torment characters), he was popular enough (especially given the relative obscurity of his race) to cause most subsequent depictions of githzerai to become similar wise and disciplined warriors. In combat, he’s a good fighter and a decent spellcaster.

Annah of the Shadows

A tiefling (a person of mixed human-demon ancestry) adoptive daughter of Pharod, a leader of the community of collectors living under The Hive’s Ragpicker Square. Annah is an impulsive, short-tempered character with a great knowledge of Sigil’s criminal underground. She’s a potential love interest for the Nameless One and she actively dislikes Fall-From-Grace. She’s a fighter and a thief, although her combat effectiveness isn’t too good and (unlike in Baldur’s Gate) trap detection isn’t needed that much. Her other thief skills can come in handy occasionally though – especially the ability to sneak through combat-heavy areas (it’s enough for her alone to reach the end of an area, because unlike Baldur’s Gate, you don’t need to ‘gather your party before venturing forth’).

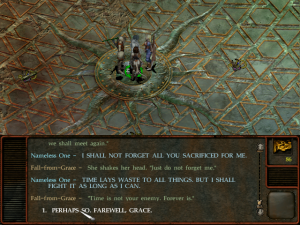

Fall-From-Grace

A character built on paradoxes: a demon who rejected chaos, a celibate succubus who owns a brothel in which nobody has sex and a priestess who doesn’t worship any god. She’s a member of Society of Sensation – an epicurean faction which focuses on experiencing as many different things as possible. Like Annah, she is a possible love interest – but her nature as a succubus means that even touching her is dangerous. As a priest, she’s a very good healer with a few useful support and offensive spells, but her inability to wield weapons makes her rather useless in melee.

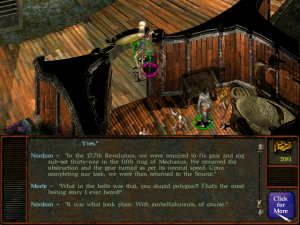

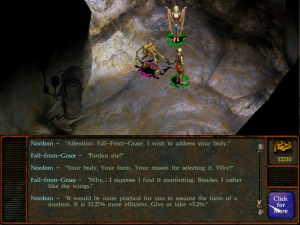

Nordom

Nordom is a modron who “went rogue” – he separated himself from the collective consciousness and attained individuality. He’s far more chaotic than any other modron in the game, but is still a mechanical construct who relies more on logic than on emotions. His dialogs are quite amusing given his overuse of technical jargon and tendency to confuse similar-sounding words. Nordom wields “gear spirits” that are conveniently shaped as crossbows and is the only purely ranged character, which makes him quite useful in combat, although the process of finding him requires a long trek through a repetitive (intentionally, but it doesn’t make it any less tedious), randomly generated ‘dungeon simulator’ filled with strong enemies.

Ignus

An insane wizard obsessed with fire who outright admits to his desire to kill everyone. As a punishment for arson, his body was turned into a portal to the Elemental Plane of Fire – something he not only survived but learned to use to his advantage. He’s the “smoldering corpse” of The Hive’s Smoldering Corpse Bar and the only way of getting his attention is to use a decanter, which can pour water on him endlessly. He is probably the best spellcaster in the game.

Vhailor

Vhailor is a member of the Mercykillers faction and as such is obsessed with ruthlessly delivering justice. He was imprisoned in Curst by one of the incarnations of the Nameless One, died in captivity and became a ghost haunting his own old armor… without even noticing it. Vhailor used to pursue the Nameless One, but with the right dialog choices it’s possible to make him join the party. It’s also possible to make him realize the errors of his obsession with punishment without a regard for mercy, which leads his spirit to stop clinging to life and leave the armor he inhabited. Vhailor is the strongest melee fighter in the game but, he may turn on the Nameless One for saying the wrong things, and he makes a peaceful solution to a certain quest impossible.

Important NPCs

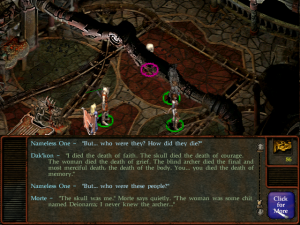

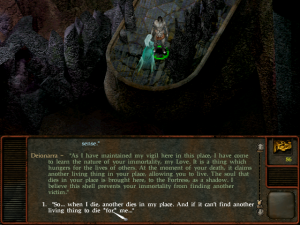

Deionarra

Deionarra used to be a lover of the Nameless One’s Practical Incarnation, who died as a result of his actions. She’s one of the game’s more tragic characters: a ghost trapped in the state of undeath by her love for someone who cared only about himself. Nameless One can promise her to look for a way to either free or join her.

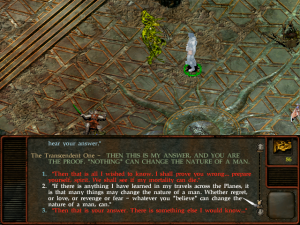

Ravel Puzzlewell

Ravel is a powerful ‘night hag’. She’s known for killing everyone who fails to answer a question she once couldn’t find an answer for: “What can change the nature of a man?” She’s the one who helped the Nameless One’s first incarnation to become immortal and as such is an important part of the game’s main story. Meeting her and having her judge the Nameless One and his companions is one of the game’s best scenes. She’s one of the few characters who needs to be fought in order to complete the game, although she’s not that tough despite having a few rather powerful spells.

Trias the Betrayer

A fallen angel who, disappointed in the gods’ inaction in fighting the forces of evil, decided to take matter into his own hands. Unfortunately for everyone, his plan involved allying himself with the evil creatures of the Lower Planes and leading them to attack neutral areas, hoping to provoke divine intervention. Another unavoidable fight, although this time much more difficult because of his ability to cast spells like Cloudkill.

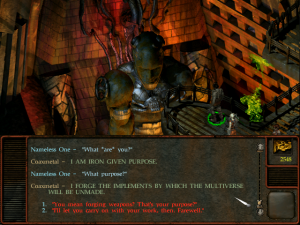

Coaxmetal

He’s a giant golem imprisoned inside the siege tower in Sigil’s Lower Ward. He forges weapons so that the inhabitants of the planes destory each other in the name of inevitable death, decay and entropy. Coaxmetal is able to create a weapon that can, kill the Nameless One under certain circumstances. It’s possible to free him, which earns a lot of chaotic alignment points.

Transcendent One

The Transcendent One is the Nameless One’s mortality. He resides in the Fortress of Regrets on the Negative Material Plane and does everything in his power to stop the Nameless One from finding him. He’s the game’s final boss and not unlike the final bosses of Fallout and Arcanum he can be ‘defeated’ through dialog options, provided you have the necessary stats or items.

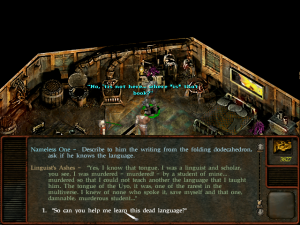

The great wall of text

While Planescape: Torment is an Infinity Engine game with most of the standard elements this implies, its appeal lies not in its cRPG mechanics but in its writing. There is a lot of text to get through in the game – and it’s not just dialog but also a lot of narration. The game does have a few pre-rendered cutscenes, but it generally doesn’t follow the ‘show, don’t tell’ principle. Some of the game’s more memorable moments – the Nameless One reattaching his eye, solving Unbroken Circle of Zerthimon or opening the bronze sphere – are communicated through writing without any sort of accompanying animation.

A lot of the writing is there to set up player choice and show the consequences of actions, but some of it is completely non-interactive, being more like a ‘text-based cutscene’. The most common examples are memories: at certain points, the protagonist will remember the events from before he woke up in Mortuary. While it would be technically possible to render many of them as FMV sequences, the decision to go with the descriptions has its advantages as it easily allows to show the character’s way of thinking and emotional state – something which would be hard to do with animated cutscenes in 1999. Other ‘text-based cutscenes’ take the form of sensory stones: magical recordings of a person’s mental state during a certain event. The majority of them have no direct relation to the game’s plot, acting more like standalone short stories – which is similar to how ‘lore books’ function in many RPGs, with the difference being that Planescape: Torment has good enough writing to make them actually interesting.

The text-heavy approach of Planescape: Torment is ultimately one of its greatest strengths. While the downplaying of D&D mechanics and the focus on writing might mean that the game sometimes feel less like a cRPG and more like a novel-length choose-your-own-adventure story, it is pretty much one of the best choose-your-own-adventure stories ever created. The RPG elements, despite the disappointing combat, are still strong enough for the game to feel like a direct descendant of Fallout and Baldur’s Gate.

City of Doors in pictures and sounds

While there is a lot of text in Planescape: Torment, that doesn’t mean that it’s not a good-looking game. While the fixed 640×480 resolution might not have been impressive even at the time of the game’s release (and doesn’t look good on widescreen monitors), the game has a marvelous art direction. The architecture of Sigil is appropriately twisted and full of sharp edges, The Hive looks like it was built with repurposed junk (although given how much time is spent there, its brown-colored streets might get a bit tiring after a while), Clerk Ward is rich and elegant while the Fortress of Regrets is dark and disorienting. All the major characters look great as well, with imaginative and often strange designs reflecting their unusual personalities. If there’s anything that doesn’t look good, it’s Curst and its surroundings – there’s just nothing too memorable about those places, maybe aside from the fact that all the inhabitants wear blades and spikes on their clothes.

The game includes a few CGI cutscenes, most of them showing the different planes when you first visit them. The best of them has to be the introductory film, which shows the Nameless One being put in The Mortuary while important parts of his previous lives are shown either directly or symbolically (including the striking image of his human self transforming into the scarred, gray-skin monstrosity he is during the game). Most of the other cutscenes aren’t that interesting, but they’re still pretty fun to watch and their low-polygon look is stylized enough so it doesn’t seem too silly.

Planescape: Torment features a soundtrack by Mark Morgan. The music of the game is defined by two things: drums and choirs. The former are very rhythmic and repetitive, giving it a sort of hypnotic quality, while the latter are soft, high-pitched and melancholic. The combination of those two creates tracks that are strange, mysterious and often sad – perfectly complementing the game’s atmosphere. The best of them has to be the Deionarra’s theme – a haunting, unforgettable take on the game’s leitmotif.

Originally, the game’s soundtrack was to be composed by Brian Williams, a British electronic musician most known for his solo project Lustmord. Management change at Interplay resulted in him being replaced by Morgan (apparently, the executives were interested in a more conventional soundtrack) and the original music was never finished, although it can be heard in some of the game’s early trailers (like this one, which was included as a bonus on the Fallout CD). Those tracks are in the ‘dark ambient’ style Lustmord is known for and are excellent examples of the genre, although they’re more of an acquired taste than Morgan’s soundtrack. Dark ambient fans and those interested in the game’s original vision should check out Lustmord’s album Metavoid, which includes remixed versions of some of the tracks meant for the game (the song for the trailer, for example, has been reworked into “The Eliminating Angel”.

Sound effects are generally good, especially when it comes to the spells. The game also has high quality voice acting, with Morte (Rob Paulsen), Ravel (Flo Di Re) and the Transcendent One (Tony Jay) standing out from the crowd. Michael T. Weiss, the voice of the Nameless One, is good too (especially when he starts talking after dying and getting brought back to life), but his lines are too few and repeated too often – ‘I’m gone’, ‘I’m hurt’ and of course ‘Updated my journal’ are heard dozens of times, which can become annoying after a while.

Technical issues

For a fairly complex 1990s RPG, Planescape: Torment runs stable and can be played from start to finish without too many noticeable bugs. Like all Infinity Engine games, it works well on modern systems but doesn’t natively support widescreen resolutions, so it might require installing a mod to solve the issue.

Some of the game’s content has not been finished and has been made inaccessible, although files and scripts are still present within the game files. Many of those removed elements can be restored with the highly recommended “Unfinished Business” mod. Other useful mods include the ones that tweak the interface and make companion AI less stupid.

Best cRPG ever?

Planescape: Torment is probably the best counterpoint against the claim that non-linear, branching narrative is inherently worse and somehow less ‘artistic’ than the more directed structure. Whether you play the game as a man seeking redemption, facing the consequences of his actions and accepting death, or as a cold and cruel egoist using everyone around him to reach his goal, Planescape: Torment is a great story. It’s a perfect example of what branching, segmented narrative can achieve when placed in the hands of good writers and combined with a great engine and a memorable audiovisual style.

The game is not without weaknesses: The interface is not as good as it could be, the combat is tedious (especially in Curst) and some of the puzzles required to finish the game can be annoyingly vague – at a certain point, you need information that can be only extracted from a wizard, who doesn’t want to talk to you unless you give him a piece of candy; while he clearly indicates that he wants candy, nothing in the game implies that you need to talk to him, he’s in the area which can only be accessed by members of a specific faction and the particular candy can only be bought from one place in the whole game. But ultimately those flaws are pretty minor considering the game’s great writing, fascinating story, memorable characters and high ammount of non-linearity.

Planescape: Torment deserves its place in the canon of the best cRPG games ever created. The game receives constant praise among the fans of the genre and none of it is undeserved. Its lasting appeal is a testament to the genre’s immense potential and to the ambitious and creative nature of the late 1990s PC gaming scene. It’s a game built on the idea of ‘avant-garde fantasy’, which doesn’t shy away from difficult themes – and it does it while still being simply fun to play.

Links:

Planescape: Torment official website mirror at Outshine

Vision document (design document for Planescape: Torment from when it was called Last Rites

Planescape Torment: What can change the nature of a man? at The Writer’s Block

Planescape: Torment Retrospective at Funambulism

Planescape: Torment shrine at RPG Classics

Infinity Engine: The Retrospective at Niche Gamer (by the author of this article)

Torment – Book (1999)

Given that Planescape: Torment had a deep story and required a lot of reading, the idea of turning it into a novel was basically a no-brainer. Unfortunately, like the Baldur’s Gate books written by Philip Athans, it didn’t work out the way it should have.

The general outline of the plot is quite similar to how the game played out at first, although as it goes on it becomes to differ more and more from the original story: there is an immortal main character who wakes up in The Mortuary with no memories, he does explore the city of Sigil with the help of Morte, Dak’kon and Annah, there is an expedition into the catacombs, the search for a night hag Ravel, a trip to Curst – but the ending is changed significantly, giving a much bigger role to Fhjull, a minor character from the video game.

Many details are completely different: Annah is a wizard now and she looks nothing like her video game – and neither does Fall-From-Grace, Ravel, Trias or many other characters. Dak’kon’s story arc is completely different, turning him into a member of Believers of the Source faction who follows the protagonist because his immortality might confirm some of the group’s philosophy and meeting with Ravel is just there to dump some exposition onto the readers. Most importantly, the Nameless One is not actually nameless – while he does not remember his original name, everyone just calls him Thane, which is supposed to be a shortened form of something from githzerai language. Some characters (e.g. Fall-From-Grace) have their roles in the story reduced drastically. Others (Ingnus, Nordom, Vhailor) don’t appear at all.

While the changes – especially to the motivations and personalities of different characters – are almost universally for the worse, that’s not the book’s biggest problem. What really kills the book is its dry, emotionless writing. The book – written by Ray and Valerie Valesse, a couple of editors who worked on a number of pen and paper RPG books for Wizards of the Coast – boils the story of Planescape: Torment down to a series of short journeys from point A to point B, with something occasionally happening along the way. It’s all very fast-paced, with most things happening over one or two paragraphs but despite that a lot events take place, almost nothing interesting ever happnes because the events don’t seem to hold any weight. Most of the characters are there just to make the plot go forward and aside from Morte and Annah, they have zero personality. Thane is the worst one of the bunch – he’s single-mindedly focused on finding his lost mortality, like game’s Practical Incarnation but unlike Practical Incarnation, his goal-oriented nature doesn’t push him to manipulate others or do any other bad things. It just pushes him to make the plot go from one place to another.

That is not to say that the book is entirely bad. It’s just an average, forgettable title, which remains completely unimpressive despite a great premise. It lacks personality, emotions and no part of the books is even remotely quotable – there’s no ‘what can change the nature of a man?’, no ‘time is not your enemy, forever is’, no ‘endure, in enduring grow strong’, no ‘I shall wait for you in death’s halls, my love’ and there’s nothing that comes close. But it’s not entirely bad and it doesn’t make the reader want to put it down instantly and go read something else – which might not be an impressive feat but is still much better than Baldur’s Gate novels with their violent and long-winded but ultimately dull descriptions of combat, which seemed to go on forever.

Like many video game tie-in novels, Torment is bland and uninteresting. It’s the book which epitomizes ‘nothing special’ – especially when compared to the game it’s based on. It’s hard to recommend it because while it’s fairly competent, it just offers nothing new to those who’ve already beaten the game (aside maybe from a different take on the ending) and for those who haven’t it’s just an inferior alternative to playing it.

Planescape: Torment – E-book (2000) /

Planescape: Torment, A Novelization – Let’s Play (2006 – 2011), E-book (2011)

Given the disappointing nature of the official Torment novel and the amount of text that can be found in the game itself, fans of Planescape: Torment decided that the logical solution to the problem would be adapting the script of the game into the format of a novel. There were two unofficial novelizations of the game created by its fans: the first by Rhys Hess in 2000, the second one by SomethingAwful user ShadowCatboy in 2011 based on his Let’s Play series of the game.

The goal of Rhys Hess’ novel seems to be to create an adaptation that is as faithful to the original script as possible (or rather of a certain path through the branching script: that of the good-aligned Nameless One), adding as little narration as required and relying mostly on the in-game dialog. As a result, it’s something that often reads more like a script than like a novel. The added narration (first person, from the perspective of the Nameless One) consists mostly of short descriptions of places, characters and actions (with the combat sequences completely underplayed, contrary to oommon trends in video game novelizations). Rhys Hess’ book is carried by the writing of Chris Avellone – and it seems that it was the intention behind it. It’s less of a reimagining as a novel and more of a translation into the format of a novel, with as little changes to the original author’s vision as possible.

A novelization written by ShadowCatboy takes a completely different approach, although it’s also written from the perspective of a good Nameless One and it even borrows some passages from the Rhys Hess version. The book (and a Let’s Play is based on – the e-book version is more or less a Let’s Play without screenshots, illustrations taken from Planescape books and links to the game soundtrack) uses the script of the game but it also adds plenty of new narration and a story-within-a-story structure. While bulk of the novel is the Nameless One describing his adventures, this is all framed in a second-person narrative in which ‘you’ sit in the tavern and listen to a group of characters read several different journals written by the game’s protagonist. As the frame story takes place in Sigil, it’s all full of the trademark weirdness of the Planescape multiverse: the journals begin as written words but in the end they’re liquid memories of the person who read and destroyed the journal, extracted from the Silver Sea. The storytellers and those who listen to them are also an unusual bunch, consisting of an angelic bard, a dwarven midget, an imp who belongs to the insane Xaositect faction and a dweller of the Astral Plane who collects lost knowledge.

Because of their different approaches, the books have more or less the opposite problems: the first one simply doesn’t bring anything new to the table and relies purely on the original script while the second one can be rather inconsistent with its writing – especially given how it was written episodically, over a period of five years. That said, both are surprisingly good reads, which capute the atmosphere of Planescape: Torment better than the official novelization.

Rhys Hess novelization, despite starting out as a completely unofficial fanwork, has received the recognition: since 2010, it’s been included as a bonus with the GOG version of the game.