For today’s gamers, Peter Molyneux’s name has become synonymous with a kind of used car salesman. Blessed with a silver tongue and a disarming ability to self-criticize (or appear to), he has time and again captured gamers’ imaginations with impossible tales that are the stuff of inspiration – though not always, as it turns out, of execution. Wandering aimlessly from studio to studio, Molyneux’s career reads like that of a restless flaneur happening upon some of the finest – and most embarrassing – moments in gaming history, from the accidental birth of the “god game” to the sleazy world of today’s freemium cash-grabs. He also has the rare honor of being one of the only gaming legends who, in a Rocks, Paper, Shotgun interview, has also been directly accused of being a pathological liar.

But before Fable’s out-of-control PR, before the artificial hype around the non-game “Milo“, or Godus Kickstarter nightmares entered the picture, Molyneux was the passionate ringleader of a small company hustling its way into the industry with shoddy ports and famously, ten ill-gotten Amiga A1000s. That day, when Molyneux walked out of Commodore’s offices having secured the Amigas on the basis of a confusion over his company’s name, marks an important turn in his own personal bildungsroman. It was here that the seed (or acorn, if you will) of Molyneux’s later grandstanding was born, and it would go on define both his relentless vision and reckless behavior as a designer.

There was always this sort of joke between everyone – the bullshit in the press again…But it wasn’t really bullshit – it was more stretching the truth.” Sean Cooper, creator of Syndicate, Kotaku interview

As Peter would have it, he was running a company called Taurus Impex, which exported not software but baked beans to the Middle East. Mistaking Taurus Impex for Torus, a company apparently known for its robust networking software, Commodore invited Molyneux & co. to come in to discuss their “product”. And the rest was history: due to his quick thinking (or lying, as Molyneux is happy to admit), the team were miraculously thrust into game design when the Amigas arrived shortly after. It is a cocktail story Molyneux tells at almost every interview and retrospective on the early days at Bullfrog.

Except that there are other versions of this story, blurring the line between truth & apocrypha with that typically Molyneux-ian ease that earned him his own dedicated Twitter parody account. According the to the book Grand Thieves & Tomb Raiders: How British Video Games Conquered the World, Taurus Impex’s “bread-and-butter income ”was none other than “contract work for databases” (p. 121). The company had actually been founded when Molyneux befriended business partner Les Edgars through the Guildford Computer Centre that Edgars ran, and its main premise was, in Edgars words, “anything to do with computers” (with other schemes, like food distribution, presumably on the side). Furthermore Torus, rather than doing any kind of ‘networking’, was a drain inspection company, whose data analysis Commodore wanted to see extrapolated and represented graphically on their Amigas. So while the call from Commodore executives was unexpected, it was not implausible: walking into Commodore’s offices, Molyneux & Edgars would have thought their meager databases had somehow gotten picked up by the big boys.

Still, it’s a rousing tale one way or another, with a core deceit that saw Molyneux’s team through its early years. The fledgling company which would become Bullfrog Productions really did have to put up or shut up, and it managed to weather the storm of misunderstanding by producing (somewhat) functional business software to make good on their promise to Commodore. But more importantly, through a healthy mix of luck and cunning, they eventually got on to what they were after all along: games.

I am a firm believer in the idea that technical limitations are often a good thing rather than a problem.” Glenn Corpes, interview with Now Gamer

In the late-1980s, the Amiga was still known more for its paint programs and video software than its gaming prowess; with prohibitively expensive, ‘professional’ versions such as the A1000, and the continuing slump brought on by the 1983 industry crash in the U.S., things did not look good for Commodore – or anyone else for that matter. But the story was different in Europe, which experienced no such crash and where many companies lived out a kind of alternate history of healthy development away from the unstable fortunes and strong personalities of the U.S. market. As new audiences were being sought internationally to move gaming from the pricey purview of a handful of hobbyists to a mass pastime, Europe (West Germany and the U.K. in particular) would emerge as a critical site for Commodore’s home gaming machine.

The Amiga hardware had wowed select audiences at the 1984 CES show but was pre-empted by the Atari ST’s release in 1985, setting the stage for a rivalry that would last for a (tech) generation. Enter the Amiga A500 in 1987, a cheaper, home consumer-targeted device built with games in mind. By 1989, Amiga was once again the ascendant faction, and with one port and an original title under their belt, Bullfrog was well on its way to treading water as an Amiga developer. But there is great irony in this: according to Glenn Corpes, art designer for Populous and creator of the experimental landscape generator that evolved into the full-fledged game, “in many ways, [Populous] was more of a dodgy Atari ST port than we liked to admit.” Programming began on Corpes’s own personal ST, which he tinkered with in the office in between other projects.

This may explain the aerodynamic simplicity of the game in comparison to the platformers, racers, and shooters that both systems were known for. Amiga games in particular were gaining a reputation for being fast and punchy envelope-pushers, brimming with cutting-edge graphical light shows. But Bullfrog’s creation was a slower burn, created not with flash but function in mind, in large part due to hardware limitations & novitiate programmers learning the ropes.

Molyneux has repeatedly claimed that it was this kind of limitation – his “incompetence as a programmer” – that led to the terrain mechanic of raising and lowering the land which became a hallmark of the Populous series. For his part, Corpes has repeatedly stated it was already in place by the time Molyneux got his hands on it (see aforementioned interview, his interview with Retro Gamer, and correspondence with Kim Justice on YouTube). It seems old Molly may have been stretching the truth again – but regardless, this kind of problem-solving became something of a “specialty and signpost of British game designers”, according to Jimmy Maher, “who, plagued by hardware limitations far more stringent than their counterparts in the United States, often used it as a way to minimize the space their games consumed in memory and on disk.” Molyneux himself has spoken of the incredibly tight space his code was packed into due to a monitor fault which made part of his work screen unusable.

On paper, then, the up-and-coming Populous was a strange bet: a slow-paced interactive simulator with stick figures on a map (‘peeps’, a neologism of Molyneux’s that never quite caught on like boardgaming’s ‘meeple’) in a sea of faster, prettier, and glitzier competitors. And yet, by the end of 1989, Populous accounted for over a third of EA’s revenue alone, inspiring a whole generation of fans and designers and guaranteeing Bullfrog’s rise to meteoric fame.

“The era of strategy gamers having to put up with game after game casting them as Roman generals, NATO commanders and nuclear submarine captains is over…With Populous you’re nothing less than an omnipotent deity with an entire world ripe and ready for the taking.” The One, April 1989.

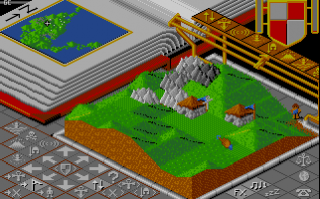

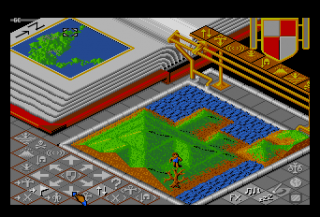

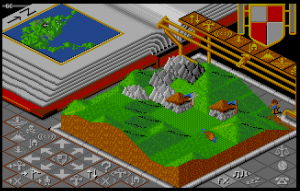

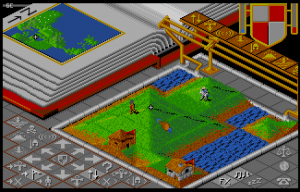

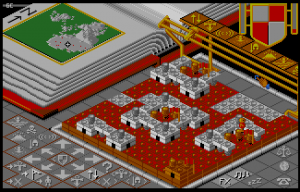

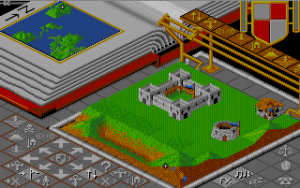

While late-game Populous devolves into the frantic, carpal-tunnel inducing clickfest which is the fate of all games of this stripe, the game begins with little pretense. In-game there is nothing but a continuous, low-chanting and an ominous, droning heart-beat that serve as the game’s only soundtrack; on an actual Amiga, the LED light pulsates in sync for added effect. Soft-blue peeps wander aimlessly in accelerated real-time, manifestly indifferent to any direct command. They scramble to build in xenophobic terror of their maroon rivals across the way; from here there is little guidance from the austere, symbolic HUD. But Populous is worth playing this way, at first – uninitiated, curious, experimental, and manic.

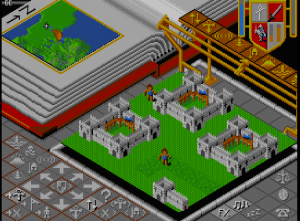

Clicking anywhere on the map (in friendly territory) will surreptitiously raise the land; right-clicking sinks the very same. Clearing the area around your peeps’ huts gives them the space to expand, while terraforming land too close to a settlement will ‘sprog’ existing peeps out to wander once again. ‘Nippling’, in the pervy boyish lingo Molyneux loved to let slip around the press, consists of rapidly raising the land upwards in one spot, either to sprog some of your own peeps or disturb your enemies’. Thankfully, settlements ruined by a sudden terrain shift re-erect themselves if the land is leveled again quickly enough, so the mechanic is forgiving rather than frustrating – it aims to keep players focused on more important matters like demographic warfare.

In the best of cases, design gives weight to abstraction, and allows for player improvisation as they make logical, thematic leaps: if I set this on fire, it will burn to the ground; if I please my followers, it will increase my strength; and so on. And while the team never thought of religious themes until late in development, the concept of divine intervention ends up creating a thematic unity that gives purpose to what would otherwise be a confusing, senseless abattoir. As Molyneux tells it, Bob Wade of ACE magazine was partially to blame, for commenting upon previewing the game that it felt like players were gods. Unsurprising with stories in the Mollyverse, Wade remembers it differently.

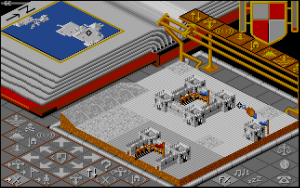

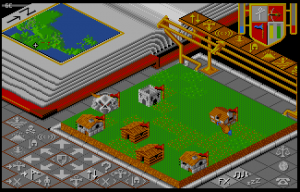

Players’ cruelty is appropriately limited, then, by their ‘manna’, depicted by a slide-rule at the top-right of the screen; a shield in the upper left depicts the health/strength and manna production of buildings and units respectively. This manna increases when your peeps are happy: that is, prospering, and growing. Growth, here, is when they have the aforementioned room for their hovels to expand into houses and eventually castles, shrinking millennia of Eurocentric development into mere seconds. And since players cannot mess with land outside of their population’s “field of vision”, they must continue pushing the limits of their frontier ever closer to the enemy to lob destruction onto their unsuspecting populace.

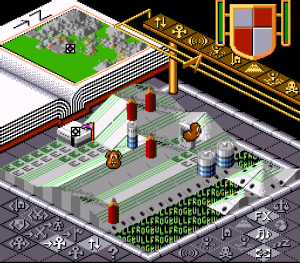

The A.I. is subtler here than it might appear, however: peeps that start out from fortresses or even stone huts will have ‘smarter’ pathfinding than their primitive counterparts, and will need less guidance if they find themselves stuck or unproductive. With time, not only are players rewarded with a slew of Biblical maladies (symbolized by tiny shockwaves, volcanoes, and floods, and even the game-ending ‘Armageddon’) which they can rain down upon their opponents, but the crucial ability to turn aimless citizens into powerful knights. These knights serve as a balance to potentially endless stalemates, and while civilian peeps are certainly capable of fighting, it is only knights who can be reliably sent out to massacre – and more importantly, who can penetrate deep into enemy lines.

As such, the early game can often be characterised as both a rush inwards and knight-wards. By following knights around around the board, even enemy land is considered ‘within reach’, allowing players to leave a trail of wanton destruction behind them. Players with quick fingers and a little patience will find that they can even drown individual enemies before the ‘evil’ deity has time to come to their rescue and re-raise the land underneath them. There’s a sadistic streak to it all – it’s no wonder that the “god game” genre eventually spawned the likes of Dungeon Keeper and even Theme Park, which encourage players to murder valiant heroes and trap customers on overpriced toilet-islands in turn.

The only other means of player intervention into the environment are the four standing orders on the lower-left, represented by a series of ideograms – ‘Settle’ (the default choice), ‘Gather then Settle’, ‘Fight then Settle’, and ‘Come to Papal Magnet’. These help shepherd the flock in critical moments by ‘gathering’ them into more powerful settlements or whipping them into a raging mob, and can be coupled powerfully with the last and most whimsically-named option, the Papal Magnet (an ankh, of all things). By placing the Magnet somewhere on the landscape and enabling this mode, all citizens will mindlessly grope towards the imposing monolith; the first peep to touch the ankh will become a ‘leader’, which is in turn the only kind of peep capable of becoming a knight.

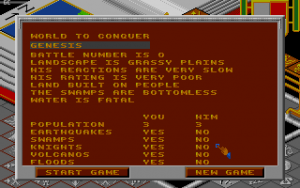

Enemy A.I. (laconically referred to as ‘HE’ in all game instructions) is a bit more of a mixed-bag. Though the game sports 500 levels of increasing difficulty, players may find that the first 50 levels feel like an extended tutorial, as they are matched with deities with very poor ratings and very slow reaction times. Most of these initial match-ups don’t even allow opponents to use any divine interventions, tilting the odds extremely in the player’s favor. Luckily, the game will skip levels to reach a more appropriate difficulty depending on player performance – a swift victory may even reward with 8 levels skipped (though it is usually far less).

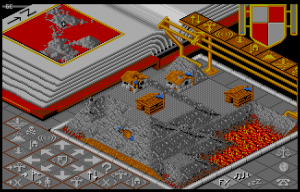

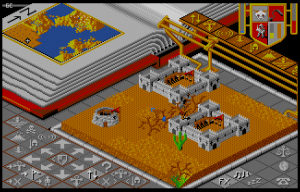

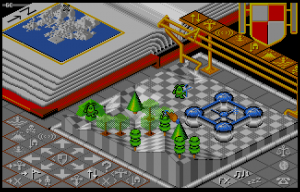

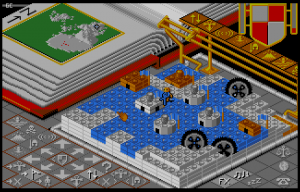

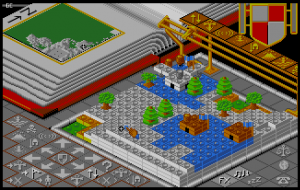

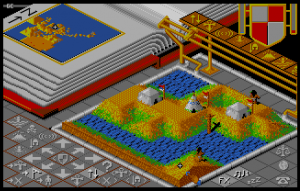

These later levels are far more unforgiving, as early earthquakes and blights arrive like a bomb with a single, thunderous MIDI note, giving players a taste of their own medicine. More importantly, terrain begins to vary after the first few levels: deserts, volcanic rock, and snow make appearances, each with their own slight tweaks on the core gameplay. Peeps are slower to expand in the snow, and quicker to expand in deserts, though they are more likely to perish in both. These levels also introduce novel restrictions, like only terraforming upwards or changing the deadliness of features like water or swamps. Expansions and other editions of Populous would enrich the variety of landscapes even further, but in the base game it is essentially 500 riffs on these same four (counting grass).

This is the heart of Populous that varies little across its half-thousand levels. But what gave the game even more life and kept it relevant for several years after its release were expansions, re-releases, and compilations with loads of additions that would extend its shelf life while Bullfrog, and their press-loving figurehead Molyneux, worked their way to the top.

“At one point Peter had a hard drive failure, there was no backup of his code and he rewrote two months of game logic in a week or so.” Glenn Corpes, interview with Now Gamer.

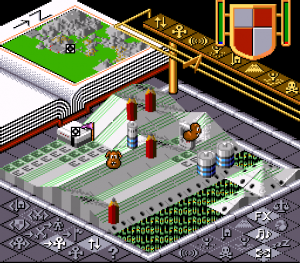

After its initial success, Populous: The Promised Lands was released just a few months later, bringing 500 more levels and 5 new terrain types: Revolution Francaise, Block Land (an homage, perhaps, to Populous’s brief foray into Lego), Bit Plains, Silly Land, and Wild West. In Bit Plains, for example, the landscape is now made of computer paper, with pencils and disks and cigarette butts instead of trees, and Spectrums/Amigas/STs/etc. (depending on your version) instead of normal buildings. Peeps themselves get a face-lift too, with stereotypical berets in France and little green men in Silly Land. These new sandboxes also have unique properties: Silly Land is actually quite harsh and causes wandering peeps to perish quickly, while Revolution Francaise is much more open and encourages quicker growth.

Promised Lands does little to change the core formula, but does offer a steeper challenge, with powerful deities right out the gate. The scope of this expansion guarantees the game’s longevity with enough variation to keep a dedicated player happy. For “just a tenner” (as the UK rags were fond of noting), players could effectively double the lifespan of their game, and the inclusion or exclusion of this map pack would become a crucial selling point in successive bundled ports of the game.

Populous: The Final Frontier is a special data disk released for the November 1989 issue of The One, a single map wherein players are to “colonise the stars” and “create space stations on vast orbiting mirrored plateaus”. The Papal Magnet is, appropriately, the logo for The One, and some effects have been modified, producing ‘crystal growth’ instead of volcanoes, and black holes to boot. This disk in particular remains hard to find.

The Populous World Editor was also released in 1991, giving players a more fine-tuned custom toolkit, including the ability to import images or use a paint tool to modify the landscape as they saw fit. Not only that, but the World Editor grants the ability to fine-tune the simulation itself, including birth/death rate of followers, manna production, and peeps’ intelligence. Interestingly, the World Editor was not designed by Bullfrog, but by two German fans, who presented their work to the team and were brought on board. This began a tradition (and occasional gimmick) that would follow Molyneux through his years, as he made no bones about preferring young upstarts to industry veterans(p. 68).

The same year also saw the release of the combination Populous/The Promised Lands, which would be re-released numerous times in later years as Populous + or Populous: Platinum Edition respectively. By this time, Populous 2 was already out, but the bargain was enough to make it a worthy purchase for many; today there is no reason to play Populous any other way.

“Publishers found that an Amiga game down-ported to other platforms carried with it a certain cachet inherited from its original version. Cinemaware, the premiere Amiga game developer and later publisher in North America, used the Amiga’s halo effect to particularly good commercial effect. All of their big releases were born, bred, and released first on the Amiga. They found that it made good commercial sense to do so, even if they ultimately sold far more copies to MS-DOS and Commodore 64 owners.” Jimmy Maher, The 68000 Wars, Part 4: Rock Lobster

Ported to the SNES, all major Sega systems of the time, Mac, DOS, and even – in a strange bit of arboreal foreboding – the Acorn Archimedes, very few gamers of this generation would have been able to avoid tripping over a copy of Populous for any one of their systems. Of course, the Amiga & ST versions, though they differ very slightly (Amiga’s superior soundchip might tip the scales for some), are largely the same – the difference here was a cultural one, similar to later console wars in that one’s choice of machine was a statement of intent, an investment in its future. Price point could may have well been the deciding factor for players then, though it is unlikely to be now.

Of all its other incarnations, the DOS and SNES counterparts are probably the most well-known. The former became the definitive version for many at a time when DOS games still sold more than Amigas themselves, and is what sites like GOG.com have available today; the latter was a launch title in Japan and was lovingly tweaked to add characteristic Nintendo flair.

Populous on DOS is not very different from its Amiga forebear, except in two crucial respects: a repetitive musical loop that became standard for most other versions of Populous, and significantly less input lag. On the Amiga, the game hangs in between launching and witnessing an earthquake, for example, whereas in this version it is instantaneous. This is enough to make it far more desirable over the Amiga version, especially for players who value intuitiveness over nostalgia factor. However, the overall sound effects/atmosphere are worse for the wear, and poor emulation can lead to a massively sped-up game. Contemporary players may want to look into reducing CPU cycles to compensate if they play this version. The game’s MAC port is an almost all respects identical to this version, with the only exception being some questionably ‘enhanced’/remixed theme music.

The SNES version, like all console versions, suffers from the lack of a mouse; while it is certainly possible to adapt, scrolling with the d-pad is cumbersome and laborious. All actions can be accessed through a string of shortcuts, but no contortions can match a mouse’s swiftness in the heat of battle. Even worse, there is no two-player functionality, a big loss given how much better it is than the base game. Still, it offers quaint twists such as Famicoms and Gameboys on its Promised Land levels (which come with the game). Wild West is now “Japanesque”, an aesthetically sleeker and politically less problematic setting (samurai replace ‘red Indians’ as rivals), and Block Land is now Cake Land (perhaps to avoid copyright infringement). It also inexplicably includes an extra world based on the Three Little Pigs. In a familiar attempt to over-sell their product, Nintendo Power praised the “life-like” graphics on the SNES (p. 71), and though they are certainly cleaner, they are noticeably shrunk down, most clearly in the HUD.

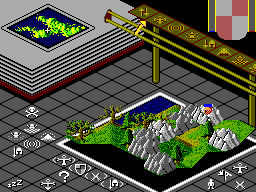

Sega console ports are an uneven lot. The Master System port by TecMagik is visibly inferior in comparison to its peers, has severely reduced music and almost no sound effects. It also prevents cheating by forcing players to progress through levels in a linear order, and lacks Promised Lands. It manages to compensate by padding in an extra – wait for it – 4,500 levels, which were no doubt randomly generated and shoved on the cartridge for marketing purposes. It is, however, far smoother than even the original Populous, especially when scrolling, a welcome respite from its otherwise barren features.

The Genesis/Mega Drive version was considered lacking in many respects at the time, though it is closer to – if slower than – the original game. So slow, in fact, that drowning peeps becomes a cinch, as rival gods have no chance of catching up. Reviewers complained that the game did not take full advantage of the hardware, though one wonders how much graphical improvement can be made on stick figures. It also retains some of the same limitations as other ports, lacking Promised Lands, a mouse, and the chanting ambiance, though it does retain a rudimentary heartbeat throughout matches.

Attesting to the irresponsible lengths the Populous fad went worldwide, a Game Boy port was also released in Europe and Japan (under the moniker “Populous Gaiden”), which has to be seen to be believed. Menus appear in chunks that need to be scrolled across just to be read, while in-game there is no HUD whatsoever: all possible actions and Acts of God are confined to a grid in the start menu, meaning players must painstakingly tab back and forth in order to do anything. Truthfully, it is a barely-playable cash-in, based on a blueprint provided by Corpes and which he has claimed (sarcastically, one hopes) was his favorite.

And of course, there are a string of ports to the other oft-forgotten architectures of the day, such as the Archimedes, PC-Engine, and Japan-only FM Towns & Sharp X68000. All of the higher-end computers tend to handle the switch with a high degree of fidelity and even some slight enhancements, such as the Sharp X68000 version’s richer, more melodic Populous loop over all stages. As for more conventional console hardware like the PC Engine, its version of Promised Lands includes a unique ‘Bomber World’, based on the Bomberman franchise, as well as some narrated cutscenes.

“Nobody that worked for Bullfrog at that time was particularly experienced or qualified, but Peter gave them such a sense of worth and self-esteem…Even though these guys were hired pretty much from the local shopping mall GameStop, he told them they were gonna be the best games company in the world.” Gary Carr, Kotaku interview

It is difficult to understate the impact Populous had on the rising game culture of the 1990s; by 1991, The One could joke that only 3 people in Britain did not own Populous, according to available sales figures at the time which placed the game at a whopping 56,000,000 units shipped. Populous became a launch-title for the SNES in Japan thanks to Imagineer, for which the designers were brought over for a rock star-style welcome in 1991, creating a “full-blown fad there that came to encompass comic books, tee-shirts, collectibles, and even a symphony concert”, according to Maher. From an obscure ‘indie’ title to the “licence to top all licences“, it spawned a whole new conception of minimalist macro-economic simulation, often earning comparisons to the one of its equally successful contemporaries, Sim City.

These two branches of the ludic tree of life have crossed more than once, with the likes of Will Wright’s Spore and Bullfrog’s own Theme games blurring the lines between these supposedly distinct phenotypes. And though there is an ongoing debate about what constitutes a “god game” versus a “sim(ulation)”, the fact that Sim City and Populous were often reviewed together and were eventually released on the same disk should lay to rest that contention. But the conflict itself is revealing about the contested beginnings of any movement or form.

Indeed, in the contemporary mania over these games, some magazines would credit Molyneux as Wright’s direct inspiration; Molyneux, for his part, even boasted once that Populous would somehow actually link up with Sim City in-game. Regardless, it is worth nothing that even though Sim City was released chronologically before Populous, the two games were actually developed simultaneously – making the birth of the god game, like the birth of modern calculus, a case of ‘multiple discovery‘.

There is one major difference between Populous and Will Wright’s urban planning masterpiece, however: it casts player choice in terms of good and evil, a theme which Wright’s games stringently avoid (though they make subtle statements about things like nuclear power). Molyneux would revisit this idea in almost every game he’s had a hand in, and while that choice is essentially linear in Populous – as there is no other kind of God to be but a vengeful, world-ending one – the roots of Molyneux’s Manichean morality plays can be seen here. In Populous, it isn’t the player launching a holy war, but their followers; by Black & White, that gap – the impersonal distance of command – is brought even further into focus, with the weight of good and evil felt in the act of being a voyeur itself. And though this may be familiar to contemporary Sims players trying to get their isometric avatars to hump each other, it was still a novelty in 1989.

Despite all of its pioneering features, however, Populous is still sluggish (even on the fastest ports), repetitive and often obtuse. The graphics are quaint but cluttered, the map is a pain to scroll around (even with a mouse), and it doesn’t reward with an upward difficulty curve. Here there is only the elliptical, unending brutality of the old-school arcade, the pride of having cracked 500 permutations on a single puzzle. It is far overshadowed by its sequel in almost every respect, as it fleshed out the incipient formula, embracing its theme in a meaningful way and offering players a chance to specialise their god to their liking.

But Populous deserves better than such harshness – for it was always a multiplayer game at its heart. Players matched each other through BBSes dedicated to online competition, and in this, Populous presaged the coming era of RTS gaming. Though critics commented on the “unusual two player mode” via a modem or serial lead (which allowed Amiga and ST users to go head to head), it turns out that single player was the after-thought; it was only by playing each other that Molyneux and his team honed the game down to its clicky, addictive core. And it shows, for Populous transforms from a curious experiment into an electric delight in the company of other humans, who are naturally more unpredictable and dastardly than the dated A.I. could ever be. The magic of two shut-ins shouting at each other from across the office in glee and terror and discovery at the weirdness of their own creation is rekindled in this multiplayer experience – so it’s worth having a friend in mind when booting up Populous again for old time’s sake.

Populous is not only about Peter Molyneux. But for better or for worse, he is that most magnetic personality around which the game formed, like a celestial body drawing detritus into its gravitational field. And there are times when old Molly did indeed seem to think of himself in such heavnly terms, as we’ve seen – Molyneux the self-aggrandiser, the boaster, the exaggerator who claimed he could “teach anyone to code in two weeks”.

But as usual, there is more to the man and to the company he helped create: the self-sacrificing leader, the passionate risk-taker, the down-to-earth, self-deprecating, visionary auteur who, like Soviet film director Andrei Tarkovsky of Stalker fame, once re-wrote his entire project after losing it all rather than throw in the towel. There is something intoxicating about Molyneux’s excitement and verve from this period, riding on the high of a string critically acclaimed games. And there is genuine maverick insight in his relentless pursuit of ‘big ideas’, which produced some of the most memorable games of early computer gaming.

Populous is crude, aged, a bit obtuse – but it would be foolish to pass it by. It contributed to the growth of a larger consciousness around the significance of games as a form of art and expression, as critics debated the theological implications of a game that allowed players to ‘become God’. And although sequels and even fan reboots have pulled it off better, the expansive spirit of early gaming culture is still alive in these masses of jittering red-and-blue peeps. So perhaps Keith Farrell of COMPUTE!’s Amiga Resource had it right when he wrote, “This, I think, is what we mean when we differentiate between computer games and videogames. Populous is a computer game, among the best ever written.”

Links:

Populous and Powermonger cover gallery Lots of comparison shots between versions

Peter Molyneux’s Kingdom in a Box Jimmy Maher’s long-form piece on Populous

The 68000 Wars, Part 4: Rock Lobster Part 4 of Jimmy Maher’s history of the home computing market of the late 1980s The Rise and Fall of Peter Molyneux Kim Justice’s thorough 5-part documentary

Retro Gamer Issue 160 Interview with Glenn Corpes on p. 92

Populous GDC Post-Mortem Molyneux walks down (rose-colored) memory lane

Glenn Corpes correspondence with Kim Justice (1); (2) Glenn Corpes clarifies some controversies and sheds light on the design process for Populous

Edge Magazine – The Making of: Populous 2009 Retrospective

Kotaku – The Man Who Promised Too Much 2014 Retrospective Interview, with a repentant Molyneux

Rock Paper Shotgun – Peter Molyneux Interview: “I haven’t got a reputation in this industry any more” The controversial ‘pathological liar’ interview

Peter Molydeux Molyneux parody Twitter account

How Game Design Works/Doesn’t Work: A Lesson from the ‘What Would Molydeux?’ Game Jam Game Jam meet-up inspired by Molydeux parody account, which would eventually bring in Molyneux himself in subsequent years

Gamespot – Molyneux on Building Populous 2011 interview, full of standard Molyneux cocktail talk

Populous to The Sims: A History of Playing God Richard Cobbett’s history of god gaming, addressing the simulation debate

From Bedrooms to Billions a documentary on “the British Video Games Industry from 1979 to the present day”; contains extras in which Molyneux expands on fine-tuning the game through multiplayer rounds

Screenshot Comparisons