It’s kind of amazing just how prolific Gainax’s work has been. The studio’s impact in anime goes without saying, but they’ve also had a surprising influence in other fields. In particular, they created a game series called Princess Maker, a strange daughter raising sim mixed with RPG elements. The series first appeared in 1991, several years before Gainax became a force with the success of Neon Genesis Evangelion, and lasted into 2008 with a fifth game and a port of the forth. However, actually talking about these games is a challenge, as fan translations are unfinished or simply not attempted for any of the series outside the first two games, and none of them ever received an official translation up until very recently (and very poorly).

Well, one did get a translation back in the 1990s, but the translation didn’t release as planned. Princess Maker 2 is a particularly interesting bit of gaming history, showing the risks localization brings. It also shows that a game can still be very influential, despite never getting a proper release for a certain region.

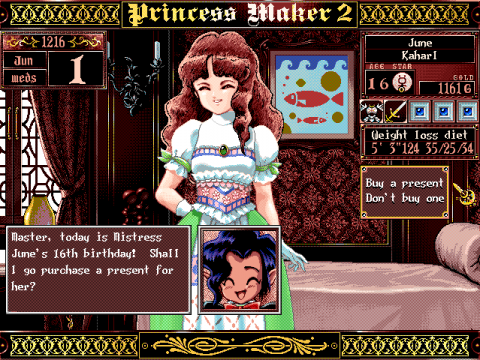

Princess Maker 2 sets itself in a medieval European fantasy world, where Lucifon (aka the devil) has come around to punish mankind for their arrogance by destroying the major kingdom of the land. This is when your character steps in, a warrior from another land who becomes a hero that defeats the demon hordes. The king grants you work at his palace and promises to change his ways, while the heavens have bigger plans for you. They send you a child from the stars to raise, a young girl who has the potential to be a great hero like yourself and set humanity on the proper path. What happens from here is up to how you raise the young girl, and the endings range from heart warming to horrific.

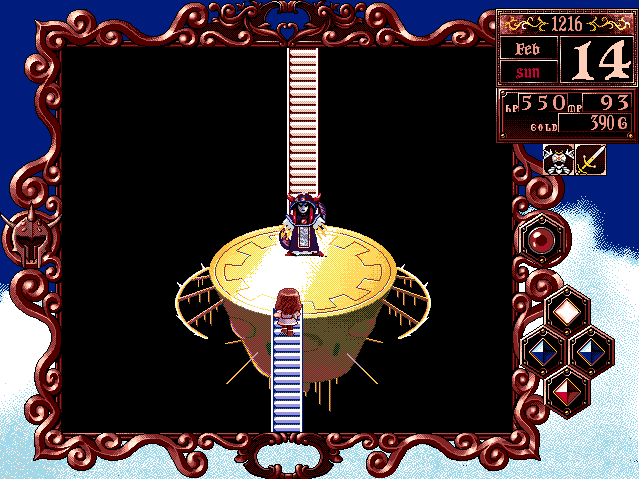

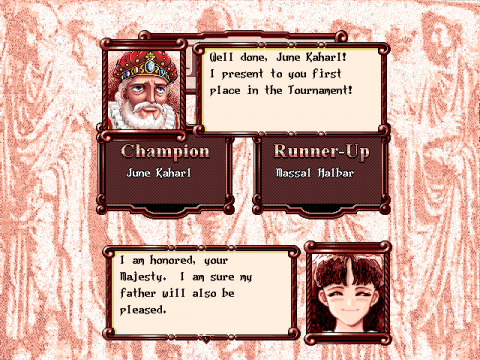

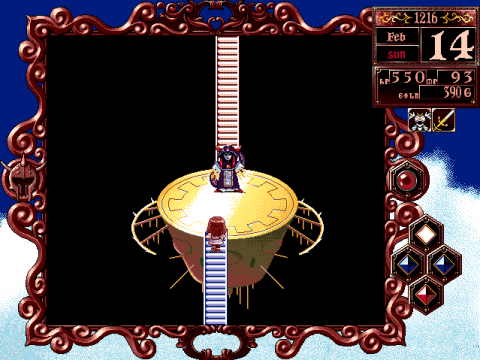

You start the game off by naming the hero and the daughter, while also deciding the daughter’s birthday and her blood type, which affects variables that change her stats. You raise her from age ten to age eighteen, sending her to do different jobs as the main breadwinner (your allowance is yearly) and learn a variety of skills from different schools. You can also visit the court to try and meet different high ranking officials and gain clout, visit shops in town for goods, and go on adventures in four different dungeon areas, each with their own special events and secrets. There’s also other special events, like the harvest festival contests, getting visits from different deities of different fields, meeting with salesmen, gaining a rival, challenges in the streets, and much more.

There are a ton of different stats that decide which of over seventy possible endings you can get. There are simple endings, like the daughter earning simple jobs or working in the arts, and much larger endings involving the gods and demons of the world. Since this is a work from the studio that would go on to make Neon Genesis Evangelion, the inclusion of bad endings isn’t surprising in the slightest. It’s not just the daughter becoming a demonic conqueror either; It’s entirely possible to be such a bad father that she becomes an amoral prostitute or criminal.

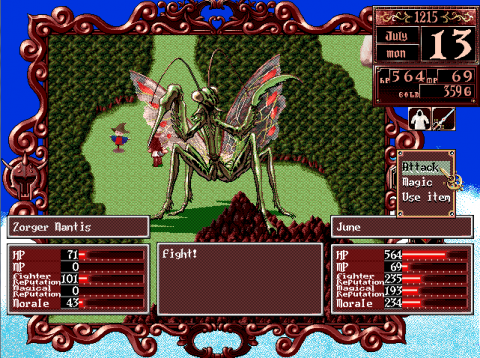

The game plays itself out in menus, as you make decisions and schedule how your daughter will spend her month. She can get tired if you overwork her, so you have to remember to give her time to rest. Her work is the main source of income for the house, and it helps her earn different skills, but risking an adventure in a dungeon area can lead to greater riches (assuming your daughter is strong enough to make the journey). Money leads to better equipment and better clothing, which in turns allows for more ability as a fighter or in trying to earn favor at the court. All other systems, like dungeon exploration and combat, are dirt simple, with simple options that have no real complexity or strategy. It’s all about learning the layout of different maps, figuring out how to trigger different events, and knowing the most basic weakness of an enemy.

Trying to increase or decrease different stats is the real challenge. While a few endings require events to trigger during the game, most all require different stats at certain levels. There’s all sorts to keep track of, from general attributes like charisma and strength, to specialized ability in combat and other fields, and even different reputations. On top of that, your daughter’s weight decides what she can wear, court popularity is measured as a separate statistic, and even breast size can be affected through a special item (remember the term “Gainaxing” exists for a reason).

Every job or school affects different stats, and can even cause some to decrease. Hair styling may pay a lot, but it also greatly decreases constitution, as does putting your daughter on a diet (necessary for certain outfits). Grave-keeping may build magical defense, which is a major help for dungeons and combat events, but it also destroys your charisma very quickly. Even hunting can build your sin ever so slightly, which can risk bad endings. You’re constantly keeping track of all these statistics, and you have to carefully plan out education in order to get the best possible endings you’re aiming for. It’s like affection statistics in visual novels with romance paths, except multiplied by the dozens and made the main focus over the narrative. This level of micro-management is oddly addictive, creating a game that can be beat in just a few short hours and instantly replayed to find something new.

This ridiculous focus on choice and decision has impacted a ton of games over the years. The Princess Maker series wasn’t the first to offer a game like this, but it was certainly one of the first series to get the formula down and had the most impact. The visual novel genre was the most affected, especially in ones that add RPG segments, but the direct influence the series has had in the west was completely unexpected.

An English translation of the second game was leaked to the internet, completely finished by a company known as SoftEgg, and instantly found an audience. People were amazed by the strange style of game, a bizarre mixture of RPG and simulation that had never really been seen before like this in the west. Its systems and ideas ended up inspiring several smaller developers, resulting in several take-offs. Most notable among them was the My Pet Protector series of Flash games (which eventually moved to mobile), in which you were tasked with raising a young hero to save the world. A much more interesting game directly inspired by the series called Long Live the Queen also came out in 2012, taking the central idea (raising a young girl to be someone special) and mixing it with violent political backstabbing and manipulation. Some have even referred to it as the “Dark Souls of visual novels,” one of the few times the comparison isn’t off base.

There’s also a series of porn game parodies called the Slave Maker series that needs to be mentioned. They’re a trilogy of Flash games that would not really have a reason to be brought up here under normal circumstances, but the third game in the series is so ridiculously huge that it dwarfs over many modern releases in terms of content. The game’s creator decided to give dev tools to members of different porn boards, resulting in a ton of different scenarios with all sorts of characters from different anime, games, and cartoons. It’s an absolute buggy mess that somehow reached over 4GB in size, up until the developer streamlined some of the unnecessary code. You don’t see many porn games somehow upping on the content over the games they parody… and the game itself shows why that should never have been attempted.

To think, all these strange games may not have ever happened if not for one very bad business decision.

The translated version was considered abandonware not long ago, though SoftEgg has since clarified that this is not truly the case and has asked that people stop circulating it (the internet has obviously not listened). The company was a group of four people in 1995 that wanted to localize the game for western markets, forming after initial failed attempts to sell the game to possible distributors, and eventually found a distributor in the form of Intracorp Entertainment. This plan backfired horribly, as Intracorp was going through bankruptcy at the time, and they tried licensing the game out to various different groups while they were slowly shutting down.

Intracorp was possibly planning to release the game under circumstances that would give them full profit (after much mishandling with other companies), and SoftEgg found no way out of the legal madness that resulted from the group’s poor management. They eventually gave up, mainly due to DOS games becoming outdated at this point, along with a growing focus on first person shooters in the PC gaming market. The game simply got localized at the wrong time and under the wrong circumstances, and the translation never got its proper release.

Tim Trzepacz, of the localizers, felt so guilty over the situation that he eventually created a special version and full manual to present to the game’s creator, Takami Akai, at an anime con, stating that “I’ve been a bad father, the daughter has turned out poorly. I am returning her to you now.” It makes one wonder how things would have gone down if the game got its proper western release. Maybe because it was found as such a strange lost gem that it gained the influence it has today, and that proper release would have lessened its mystique. Maybe, it would have been a surprise hit. Maybe that bizarrely massive porn parody would have never happened.

Maybe, that one particular outcome would have been for the best.

Links:

SoftEgg Enterprises: The story behind the Princess Maker 2 translation from the translators.