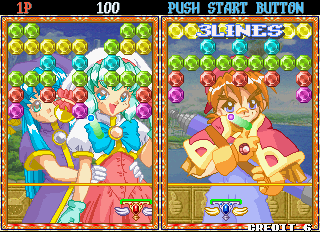

Taito’s Puchi Carat fuses two of the company’s titles, combining the brick-breaking of Arkanoid and the competitive action of Puzzle Bubble. The player controls a paddle, launching it at a screen full of gradually descending multicolored gems (named “stones”) to clear them from the screen. Combo fuel comes in the form of “roots,” the stones which connect those below them. Breaking off large swathes of stones will cause them to fall off the screen, as in Puzzle Bobble. When battling opponents, these severed stones will generate grey variants which will litter their screen and obscure their shots. A large amount of dropped stones will also lower the screen with more rows of stones. Sparkling “shiny stones” will clear all stones of their corresponding colour, with the lurid “all clear stone” destroying everything on-screen. Hard stones require two hits to remove, whilst the aptly titled, golden “annoying stone” can only be removed by its roots.

The strategy doesn’t end there, though. If your ball misses the paddle, it’ll generate three rows of stones onto your screen before rebounding back into the fray. This isn’t the end of the world, in fact, it’s often necessary in creating more root opportunities for overloading enemies with an unplayable screen dump. In this fashion you can risk intentionally overwhelming your own screen in the hopes of a game winning blow, turning defeat into a counterattack and changing the tide of a game in an instant.

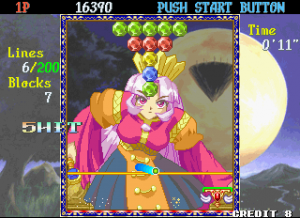

If all of this seems simple, it’s because it is. Puchi Carat is a high-risk game that prioritizes its frantic pacing and lively presentation over any kind of innovative complexity, but this is honestly to its credit; when plastered with uneven patterns of stones it can be tricky to even catch the ball at the right angle to mount any serious offense. Hitting the wrong, low hanging stone could see the ball rapidly ricocheting from ceiling to floor, ending your run in a flash. This all applies to opponents as well, but further up the VS ladder you’ll start to feel totally overmatched. With gameplay so fast and paddle controls so sensitive, it regularly forces the player to think three moves ahead, while the CPU always seems one hit away from a coup de grace. With all of this in mind, Puchi Carat’s loyalty to straightforward block breaking conventions is its only small mercy. Also included is a two-player VS mode and “testing mode,” a one player mode where your goal is to break a specific number of stone lines depending on difficulty.

Whilst the game might speed ahead on retrodden ground, it doesn’t mean it can’t try and have a good time doing it. One of the game’s biggest differences from its contemporaries is its unorthodox emphasis on story, lore and characters. As easy as it might be to compare puzzlers and plot to oil and water, Puchi Carat makes a good go of a narrative. Situated in a vague overworld named “The Kingdom of Gemstones,” the practices of science and magic intertwine, powered by the forces of 12 magical gems. These stones, fabled for their wish granting abilities and gifts of prosperity were stolen before the game’s events. This caused the kingdom to fall into the hands of powerful sorcerers, whilst the gemstones became misplaced for centuries.

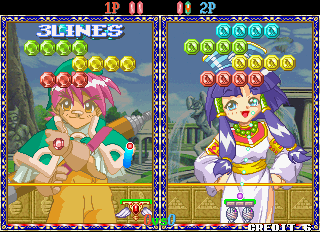

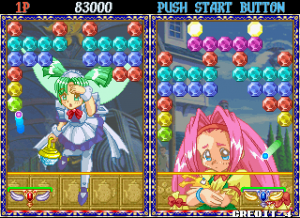

That’s where your quirky characters come in. The cast has each found themselves in the possession of a secret stone, travelling the land in search of the rest to make their dreams a reality. Visually, the game borrows from anime tropes and designs, including Garnet, a plucky, naive, distinctly protagonist-looking youth to stoic mages like Shelito. The game isn’t afraid to get goofy either, with the likes of By, a sorcerer turned into a strange rabbit-like animal hybrid who simply wants to undo his misfortune. Patraco from Cleopatra Fortune also shows up as a hidden character.

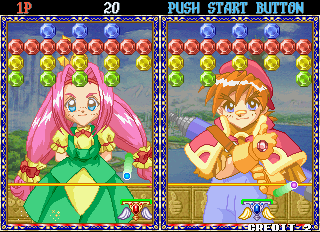

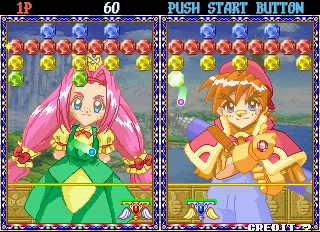

Each character has their own set of interactions for the whole roster to build a sense of personality throughout the campaign (though these are absent in the European and American versions). Their differences extend to gameplay too, as each character has unique attack patterns, the manner in which grey forward stones will fall. Some characters drop stones more to the left, others to the right and so on. The biggest struggle will be memorizing these patterns to formulate deeper strategies, as less advanced players will already have their hands full. Characters react to the play of each game, flailing, screeching and cheering depending on how they fare. In a game as bright as this one, their antics can border on garish and may be distracting to some, but there’s an argument to say it’s all a part of Puchi Carat’s ultra-animated personality. It’s all truly a matter of preference, but in a game that can end rounds in an instant it at least makes sense that the visuals might reflect the pacing. The soundtrack adds a whimsical calmness to the package, with Zuntata’s cheery injection of dreamy keys and on-brand catchiness, even if no tracks really stick out.

When the game was released in arcades in 1997, it didn’t take off, potentially owing blame to its demanding gameplay and Breakout clone fatigue. Europe and Japan received ports for the PlayStation, with Japan’s release coming in 1999 and Europe getting their first release in 2000, published by Event Horizon with a “special edition” that bundled a flimsy recreation of Taito’s paddle controller. It also supports Namco’s Volume Controller, which features a paddle that replicates the original arcade controls.

This console port features an anime FMV opening and gives players a Time Attack variation on the story mode, as well as Rapid mode, which functions as an endless version to push players to their limits. The game is mostly faithful to its arcade original, with the unfortunate distinction of skipping certain character frames, leading to choppier background animations. Overall, the port provides players with a more complete package, finally adding character dialogue between fights that were missing in the English arcade version. Finally, the PS1 allows players to take on foes in any order, which mostly influences the game’s ending. Each character has a “good “odd“ and “bad” end, depending on how fast you complete the story and the order you choose to face enemies, providing yet another challenge for pros.

Puchi Carat also received a surprisingly dense version for the Game Boy Color. Taito handled the Japanese version, released April of 1999, whilst Event Horizon returned for PAL publishing duties in December of 2000. The port retained every mode from its console counterpart with its own, similar take on story mode. It offers new characters to unlock and a card trading gimmick via the link cable for unlockable character cards found in the game. It goes without saying that Puchi Carat’s signature pace takes a big hit, with the once spritely character backgrounds replaced with small chibi imitations that stand beside the screen. The game also works on the original Gameboy, subtly reshaping the stones to compensate for their missing colours.

All in all, Puchi Carat has done surprisingly well for such an obscure title. Taito have given the game a regular lease of life thanks to ports on the PlayStation 2, Xbox and PC versions of Taito Memories in 2005. This also includes the western Taito Legends compilation in late 2006. Puchi Carat’s most recent outing comes in the form of Taito’s celebrated tabletop unit, the Taito Egret II Mini, where it’s one of 10 games bundled with the Trackball and Paddle Expansion set. The paddle gives players the chance to play the game as originally intended, with the caveat of a seriously steep price point. For hardcore enthusiasts of Taito or Puchi Carat, the novelty of arcade authenticity should be worth the price.