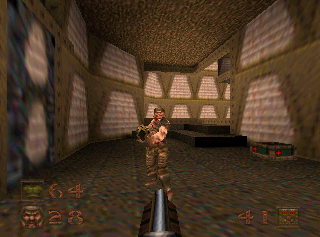

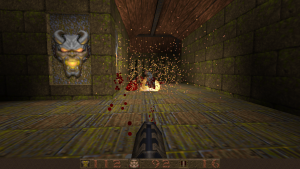

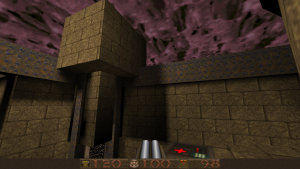

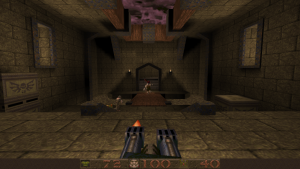

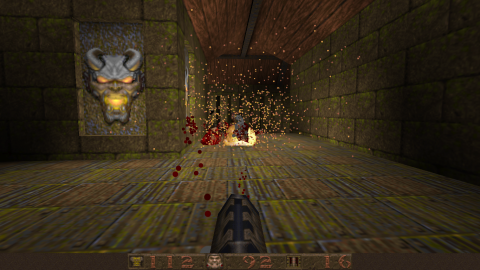

Screenshots taken were made with the source port Mark V.

Wolfenstein 3D and Doom are heralded as some of the first great first-person shooters, still fondly remembered today. And yet the same can’t be said for its follow-up, Quake. Despite having four entries, it isn’t spoken about with the same reverence, largely due to just how scattershot the franchise focus became. Though, at first, it was simply full 3D DOOM with a Lovecraft theme.

Quake was id Software’s major project after establishing the DOOM series, starting as a passion project of John Romero, first an action side-scroller, then an ambitious action RPG inspired by Virtua Fighter and the Zelda series about an awesome warrior man with a big hammer and hints of areas based on real world time periods. The rest of the team eventually got tired of trying to make the then extremely ambitious idea work, possibly not helped by Romero’s deathmatch addiction that eventually resulted in him leaving the studio shortly after Quake released. He later released a project with Ion Storm closer to his vision in Daikatana, which you may remember as one of the biggest disappointments in gaming history, certainly not for a lack of trying.

Funny enough, Romero is on the record saying he had more fun making his flop than the big success story of Quake. This starts making more sense when you realize that John Carmack, in the development of this game, literally hammered down the walls of the office so he could keep a closer eye on the team for crunch mode. The story of Quake is one of mass burn out, confusion, and boiling frustration. It is also one of the single most important games ever released.

John Carmack’s Quake Engine, commonly called id Tech 2 when that’s the sequel’s engine, completely changed what the gaming landscape was. It was the single most efficient way of rendering polygons in the mid 90s, suddenly making extremely costly full 3D game development viable. Quake even helped sell more expensive systems that could render high end graphics like this, opening the flood gates for other studios trying to challenge the kings of the FPS, including Monolith’s Blood II and Epic’s Unreal series.

Like DOOM before it, Quake also changed how FPS games were designed through technological advancements. Games like DOOM were referred to at the time as not being “true” 3D, because while you could create areas of various heights, you couldn’t, for example, place a room on top of another room. The Build Engine had a similar limitation but got around it with assorted trickery. id Tech 2 eliminates this limitations, and the worlds are now completely 3D, adding in a new level of vertical freedom. Being able to move the camera up and down was a game changer (though games like Heretic and Duke Nukem 3D experimented with it mildly), and every single modern FPS owes what id did here a great deal of gratitude. You can properly jump now, too, plus more realistic movement physics. There’s also water, where you can swim up and down. Also new is more robust lighting features. DOOM allowed maps to have individually lit sectors, but most actual effects, like shadows, were faked and built into the level designs. Quake, on the other hand, has lightmaps and 3D light sources which is evident in the glowing of your weaponry.

Like DOOM, the story is mostly an excuse for gameplay, You play as The Ranger, who has witnessed before the game armies of thralled soldiers pouring out of slip gates to test the armed might of humanity. He’s the last person alive who can stop that. Each episode starts with a fight in a military base against these soldiers and some mean dogs, you hit the slip gate, and then it’s time to explode a bunch of eldritch creatures inside a series of vaguely abstract nightmare realms. There’s still some goofy humor though, like some hilarious bits of text at the end of every episode (“She is behind all the terrible plotting!”).

Fundamentally, the game plays much like DOOM or most of other first-person shooters of the mid-90s, entirely around key hunts. The weapon set is stripped down a bit, though. The pistol is out, having been replaced with an extremely accurate shotgun. A double barreled super version also exists, and the chaingun has been traded for the nailgun and super nailgun variant. These fire projectiles instead of just being hit scan damage dealers. The rocket launcher is still present, but the plasma gun and BFG have also been replaced by the grenade launcher, able to shoot grenades off walls to get enemies around the corner, and the thunderbolt, a stream of electric pain that can do a ton to those it hits. With the rocket launcher, you can “rocket jump”, a technique executed by firing downwards with an explosive and using that force to propel you higher than you’d normally be able to jump. You have to be careful with this, since it does technically cause yourself damage, but if you pull it off correctly, it’ll be minimal. If you fire the thunderbolt into water, it’ll electrocute anything swimming in it…including yourself, if you’re careless. The expansions Scourge of Armagon and Dissolution of Eternity also add some goofy stuff, like a mine launcher, a grappling hook for deathmatching, and hilariously, John Romero’s much desired magic hammer.

Weapons in the base game are all well balanced and have clear purpose, their own uses and trade-offs. Enemies are also well designed, even with their still rudimentary AI. Like in DOOM, they all have a clear use and are placed in levels to force you to be prepared for unexpected mobs and surprises. The fiend jumps around to melee you, while knights and death knights go for the charge. Ogres can chainsaw you up close but otherwise toss out grenades and require you to dodge their nonsense and get back on the offensive. Shamblers tank and can only damage you when you’re in their sight, while the equally tanky Vores can shoot impossible to escape homing missiles and should be taken out as soon as possible. You have to read the mob and figure out what threats need to be taken care of first while keeping your ammo in check, as any well designed FPS should.

The single player campaign only works as well as it can due to the map design of Tim Willits (mainly episode 1), John Romero (lead episode 2), American McGee (most of episode 3), and Sandy Peterson (almost all of episode 4). This feels like a classic id shooter entirely because of their given creative whims they put into their maps that becomes rarer from the studio after this game. You’re not gonna see cruel moves like the ogre cabinet room or the Vore labyrinth and spawn party surprise in Quake II. They also use different styles aesthetically, like McGee’s levels using a lot of lava, or the darker feel of Peterson’s maps, especially in episode four.

The game’s look is mainly due to the three man art team of Kevin Cloud, Paul Steed, and Adrian Carmack (no relation). However, the game’s uniting feature that makes it stick out so well today is the music and sound design, handled by Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails fame. His moody score almost sounds like it’s creeping up on you, handling the Lovecraftian atmosphere almost entirely by itself. If you’re wondering why he’s here, it’s the same reason Tim Willits is – they really, really liked DOOM.

What is odd about playing Quake today is that it was built to run on first generation Pentium machines, complete with limited animations meant to look proper with choppy and limited frames. Playing it at 60 FPS today does have some odd bits to it, like the lightning effect having very limited animation, and the knights just kind of floating at times as they rush towards you. It kind of works, what with the whole eldritch horror vibe of the game, but it was clearly made for systems that hovered around 30 FPS.

If you want to play Quake today, you can easily purchase it, but you will have to download the soundtrack elsewhere and place it in the game files for it to play with the game correctly. You will also need to use a fan made source port, Dark Places and Mark V probably being the most authentic to the original look. Two mission packs by Hipnotic Interactive and Rogue Entertainment were originally released and are also up for purchase, sometimes bundled with the main game, and MachineGames of modern Wolfenstein fame made a 2016 expansion for free called Dimensions of the Past.

There were two consoles ports at the time. The Saturn port was handled by Lobotomy Entertainment, who was also behind the console ports of Powerslave. The id Tech 2 Engine was far too demanding to run on the meager Saturn, so instead the entire game was ported to use their SlaveDriver engine, also used in Powerslave. As with many other console ports of the era, some levels have been redesigned to reduce stress on the engine, but for the most part, it’s a fairly faithful conversion, and even includes some extra colored lighting effects. Four maps from the original game are gone, but replaced by four brand new ones, along with an unlockable “Dank & Scuz” comic. These are like a predecessor to the machinima videos that would become popular in the succeeding years, consisting of snapshots from the game, with goofy comic book dialogue and voiceovers, putting some Quake heroes in humorous situations. The Nintendo 64 port came courtesy of Midway Games, developed by the same team as Doom 64. This version is missing several levels, plus the soundtrack had to be altered due to the lack of CD audio, but still sounds pretty similar. The Nintendo 64 version lacks co-op but has two player deathmatch; the Saturn version lacks multiplayer altogether. The games run well considering their hardware, but only about what a low-end Pentium running in VGA mode would at the time.

We’d get a sequel to Quake just a year later – sort of. With Romero gone by this point, things took a different direction, and we got the game that one can point to as the moment id entered its third phase. The studio can be divided into pre-DOOM, post-DOOM, post-Quake II, and post-DOOM 2016. The post-Quake II years are some of the less beloved.

Screenshot Comparisons