Since Blade of Destiny was officially titled part of a trilogy and prompted for a final save after its ending, players knew they could expect more Arkania goodness sooner or later. Two years and five months later, to be exact, Star Trail hit the stores. As expected, the player’s own party from the first game could be imported into the game, though not without trouble. More often than not, some of the heroes’ portraits would be replaced with silly kids’ faces. This problem was never solved officially, with the only cure being manual correction via HEX-editor.

After being imported (and corrected) successfully, the party would once again start in a temple, this time in a small village called Kvirasim, which lies in an area near the river Svellt, east of their former base of operations. As soon as the group steps out on the streets, they get entangled in the next adventure, of course. An elf introducing himself as Elsurion Starlight, embassador of the elven King, trusts them with the search for the Salamander Stone, an artifact symbolizing the former friendship of elves and dwarves. Those two races united are supposed to have successfully pushed back a mighty orcish army in the past. According to Elsurion, only a renewed alliance of the two can avert the current threat, which has become more urgent than before: While the heroes saved Thorwal from the attack, they merely diverted the course of the orcish army, and all the bigger towns in the Svelltdale are now under siege.

As soon as the elf takes his leave, another “client” has something else to propose. This time it’s a rather dubious tradesman called Sudran Alatzer. He shakes off everything the elf claimed as lies, and instead of bringing the stone to the dwarven prince Ingramosch, as Elsurion asked, he suggests selling it to his collaborator. Conveniently, both are located in the besieged city of Lowangen. The question that remains is: Where to find the Salamander stone.

But not enough: On the party’s first night’s stay in an inn, a thief sneaks into their room, or more precisely a servant of Phex, the god of thieves. He as well brings with him another task for the heroes. The magic axe Star Trail, a divine weapon belonging to Phex has been lost and needs to be retrieved. The intruder then makes his not so dexterous retreat, and the player is left alone with these two-and-a-half rather vaguely formulated quests.

So the detective work begins. In place of the simple multiple-choice dialogues from Blade of Destiny, possible informants are now questioned via keywords. And a possible informant is just about everyone; shop owners, priests, healers – even some of the commoners can be harassed in their houses. And quite a lot of them have to be interrogated, as Star Trail is the heaviest offender for obfuscated design out of the trilogy. The only valuable piece of information for the search after Star Trail is the fact that it is missing. Or maybe even worse is the city where a special way to get out is needed, but the player is given no hint whatsoever where to look for it. Sometimes logical thinking helps – it makes sense to ask for a divine throwing axe at places where people know a lot about weapons, for example – but at other times there’s no other way as to systematically comb through all the houses in a given town. The fact that most correspondents end the dialogue after two or three questions, so that their house needs to be entered again, doesn’t help either. This makes for a lot of tough, realistic investigative work, but those used to modern games holding their hands on every step should brace themselves for for frustration.

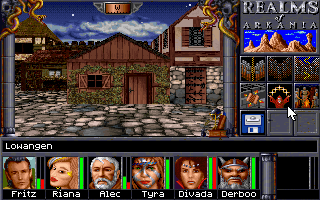

At least orientation is now much easier, as Attic switched to a realtime 3D Engine for the sequel. The different types of businesses finally got their individual textures, and even though most towns partly share the same texture sets, each is given its own atmosphere through their arrangement. The new engine also makes is possible to move around freely, although the game still defaults to a tiled walking method. Tilting the view up or down is also implemented, but never really necessary or helpful.

The automap was also vastly improved, and can be switched between two different zoom levels. Stores are marked with their names, and the player can add annotations wherever needed. Best of all, in friendly surroundings the party can be freely moved to any visited spot on the map by double clicking it, getting rid of long searches for the healer that’s tucked away in a corner of the town. To reach the same effect in dungeons, the Transversalis spell is still needed, though.

Thankfully, the developers also cut back on useless content. Only six settlements, which all are important to one quest or another, can be explored extensively. All the other villages only exist as a choice of two or three buildings, usually inns or temples. It’s just a necessary design choice, cause searching 50 towns for info the way it is done in Star Trail would have killed the game. On the other hand, it can be irritating to have to travel to a far major town just to buy a new pair of shoes.

Which leads to the newly improved travel mode. The simulation aspect has been built up a lot, with shoes wearing off only being one of the results. Illnesses as the result of improper preparation (which now also requires accounting for weather changes) are much more common, and it’s not unlikely anymore for the party to run out of food completely. Other than in Blade of Destiny, where the routes between towns were fixed, directions now can be changed at any parting of ways. Hidden routes wait to be discovered, as do unknown dangers. After travel felt annoyingly mechanic in the first game after a short while, the whole process has become much more engaging.

The level of detail given to every aspect of the game is just incredible. Aside from the aforementioned expendable shoes and whetstones that can now be used to lengthen the life of slightly battered weapons, players also have to take care their heroes get dressed up again after losing their pants in a swamp, lest they’re bound to run into trouble when walking around towns. Also neat are encounters like the forest gnomes that jump out of the undergrowth to attack only the party members that wield axes, and disappear just as fast as they assaulted the possible threat to the forest.

The same motto for the towns applies to dungeons as well. The liquidation of any quest-unrelated locations means less, but much more refined content. The few remaining dungeons are stuffed with puzzles, traps and interesting encounters. Most dungeons consist of multiple levels now, and each one has its very own set of graphics. Sometimes there are even unique tilesets for different levels of the same dungeon, and various special objects that are now presented visually. Character sprites in 3D mode do exist now, but are very few and far between, which makes the locations feel rather lonely at times.

The seventh party slot is once again reserved for NPCs picked up on the journey, but their recruitment isn’t confined to bars anymore. Most of the ones in Star Trail are more or less related to the current quest, and have their own motivation to follow you temporarily. On the other hand, that means some NPCs only join during the context of the quest, and don’t stay with the group for very long.

Star Trail is much less combat-heavy than its predecessor. Just as much time is spent in towns and on travels as in dungeons, and even one of the bigger ones holds almost no hostile encounters at all. Nonetheless, the combat was tuned quite a bit. Most importantly, a line of fire is now generated for ranged weapons and spells, so that the archer or caster doesn’t have to be aligned in a straight row with the target any more. This means that even completely surrounded enemies fall prey to their projectiles, making them much more useful. Diagonal attacks for melee weapons still aren’t possible, though. Automatic combat can now be activated for each hero respectively, and for impatient adventurers, there’s also an option to calculate the combat showing status bars, completely without displaying the movements. This of course is even more dangerous than the other options, as by the time one notices things are going the wrong way, it is usually already too late to react. It can be useful for imported groups from the first game, who tend to end up a bit overpowered in some areas. For strong parties the game also holds some extraordinarily tough, but avoidable challenges.

Less reliance on combat doesn’t mean that the quest is going to be a walk in the park, though. On the contrary, Star Trail features more instant deaths and possible dead ends than any other game in the series, and not even towns are an exception here, so it is pretty much mandatory to keep a number of backup saves, in case something goes wrong and isn’t noticed until much later. To compensate for this, the arbitrary limitation to five savegames is gone, as is the EXP penalty for saving outside of temples. A detailed description can also be appended to each save file now, making them much more manageable.

The battle screen looks mostly the same, but there are more different enemy types as well, and even two big enemies, although those don’t move on the battlefield. Enemies of the same character class as the heroes have been given distinctive sprites, too.

The rest of the interface didn’t miss out either. Every accessory item class, like necklaces/amulets, rings and belts finally got their own equipment slot, so all the magic items found in Blade of Destiny can finally be equipped to waste less space in the limited inventory. Short animations are played when putting them on, but those are somewhat limited. For example, male heroes always wear boots in the animation, while it’s sandals for the women, no matter what kind of shoes are used in the actual game. After the first game required a lot of guesswork for the weapons of choice, their damage values can now be displayed by looking at them. Magic items are marked as well, but only after being analyzed once.

Despite the massive improvements, Star Trail also brings a few drawbacks, though. The game gives less feedback at times, so it is still possible to randomly lose items at certain events, but the game won’t even tell players about the loss, leaving them wonder where that special important key went hours later. Gained experience after a battle isn’t displayed either, but in turn the amount of EXP necessary for the next level can be prompted from the inventory screen.

Some important events are presented in fully voiced cutscenes, and all spells are now said aloud, too. The English voice acting in itself is rather solid (better than the original German version), but the sentences sound a bit disjointed in between on-screen text lines, almost as if they’ve been recorded separately.

Like Blade of Destiny, Star Trail was released on both floppy disks and CD-ROM (an Amiga version was out of the picture, of course). This time, the gap in audio quality is smaller, but it was still a shame that the CD version didn’t get a proper re-release for the longest time – it was cut down from two discs to a single CD, which contained even less audio tracks than the former disc one, cutting the soundtrack down to a meager 11 tracks from the original 42. Worst of all, the player was often forced to switch off CD music manually in order to progress further in the game. Unfortunately for English language users, to this day even on download platforms, only the German version of the game is available with the full CD audio.

Bugs are once again a problem, just as much as they were in Blade of Destiny. Some old bugs were fixed, but others weren’t, and there’s a share of new ones as well. Most are just annoying, like the aforementioned kids’ faces bug, but there’s also a few almost game breaking ones as well. The English version got “updated” again with unique bugs that weren’t present in the original German game, the worst of which renders the game almost non-completable when not knowing it, but can be easily fixed/avoided with the right hints.

Star Trail is often considered the best game in the series, and was crowned RPG of the year 1994 all over the place, by magazines and players alike. However, nowadays it can only be seen as somewhat of an acquired taste, and interested players have to put up with a lot of hardships before they can truly appreciate the game for its merits. For fans of classical hardcore RPGs, it can prove a true revelation, though, especially for those that prefer simulation-heavy experiences.