Most of the shooter competition games of the late ‘80s and early ‘90s used a similar template – a score attack mode, with stages that typically aren’t that difficult to survive, but with the actual goal being to obtain as many points as possible within a time limit. Recca, the game used in the Naxat 1992 Summer Carnival competition, comes at it from a different angle – there’s a scoring component, sure, but it’s such a ferocious, blisteringly fast paced, incredibly difficult title that just lasting five minutes is a minor accomplishment. Appropriately, Recca is also spelled “rekka” in Japanese, with means “flames”, suitable for a game that exemplifies such blazing intensity.

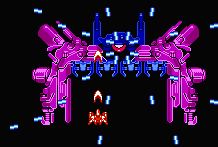

From the moment your ship blasts off from its space carrier, there’s barely a moment to breathe. Dozens of enemy drones zoom around, entering and exiting the screen within a second or two. Bosses appear almost immediately and attack without warning. Very little is telegraphed, if only because there’s no time for it – it’s a game that demands reliance on either memorization or instincts.

There are five different primary weapons for your ship, ranging from spread bullets to lasers to homing shots, each with different trade-offs for power versus versatility. There are also five more subweapons that take the form of rotating pods around your ship, that fire in various directions, and can be obtained to complement your weapon. Even though you lose all of your weapons when destroyed, power-up capsules are dropped so frequently that you can be back to full strength within mere seconds. 1ups are also hidden among regular enemies, requiring that you efficiently destroy the hundreds of enemy waves that make up each stage.

Although Recca predates the “bullet hell” designation that started a few years later with Batsugun and Dodonpachi, there are some early traces of it, particularly in the rapid spread patterns of boss attacks. However, actually dodging these is nearly impossible – the fire is too thick, and your ship’s hitbox is too large. Instead, you have a unique charge shield weapon. If you lay off the fire button (a tough thing to do considering the screen usually has at least a dozen enemies at given time), then you’ll slowly start collecting an energy ball at the front of your ship, which can absorb standard enemy fire. It cannot, however, absorb the lasers used by bosses. Knowing when impossibly thick bullet patterns are coming so you can activate this is key to most boss encounters. Plus, once you do fire, the energy ball will detonate into a screen clearing bomb, giving you a powerful weapon that you can use at any time, providing you know the proper spots to charge it.

There are technically only four levels to the main game of Recca, the last stage being a boss rush consisting of both new and old bosses. Beat this, and you can play a harder mode, which is seven stages total, and rearranges the game’s levels, patterns, and bosses to be even more difficult. There’s also a hidden “zanki” mode, where you get fifty lives but enemies fire spread suicide bullets, with bonuses being given out for beating the game with remaining lives. There’s also a cheat mode where you can listen to music and select your stage, accompanied by a goofy looking girl called Recca-chan.

Recca‘s position as a competition cartridge puts in a different situation from most other console shoot-em-ups. Typically these games have some pretense of fairness – it wants you to play for a long time, without getting too frustrated, so they have difficulty curves to ease you into high levels of play. Recca makes no such concessions – the goal really isn’t to beat the game at all but rather to survive as long as possible. Beating the game is possible, of course, but it’s really only for the most dedicated shoot-em-up fans. That’s both a positive and a negative for Recca – it’s an exhilarating, almost non-stop roller coaster, with an unmatched feeling of excitement, but playing the same five minutes over and over just to barely scrape farther eventually grows tiresome. As such, unless you really want to sit down and devote the hours required the beat the game, it can become tiring, and is best played in short bursts rather than continuous long term play.

Recca‘s blistering speed make it a technical showpiece for the Famicom, and it goes above and beyond practically every other shoot-em-up in existence. There’s a fair amount of flicker, but it’s rarely enough of a problem to kill you, and while there are a few spots of slowdown, they’re a welcome reprieve from the intensity of the experience. The visuals make fair use of the sine wave scanline manipulation function, like the flames on the title screen, or other effects, like the purple waving smoke seen in the second half of the first stage. Technically there’s not much variation in the backgrounds, but it all goes by so quickly that it hardly makes a difference, plus the focus is on the foreground action anyway. Many bosses have multi-sprite segmented limbs, animated with insect-like precision, creating an effect typically on seen on technically proficient Genesis games. And this is on a Famicom!

The high tempo music is also incredible. It’s the closest you’ll get to hardcore techno on the Famicom, complete with fierce percussion and sound samples. It does get abrasive at parts but it adds to the ferocity of the experience. The only problem is that it tends to get drowned out by all the bullet noises and explosions. The soundtrack was composed by Nobuyuki Shioda, who never quite got to work on something as stellar as Recca throughout his career.

While it was published by Naxat, Recca was actually developed by KID, a company that typically worked on titles made for the American market for their company’s overseas brand, Taxan. These include games like Low-G-Man, GI Joe, and Kick Master, which were generally pretty decent. But their programming was often a little dodgy, with choppy animation or scrolling, so it’s surprising that Recca is as solid as it is. That talent is owed to Shinobu Yagawa, a young programmer who, by this point, had clearly honed his craft. After his time at KID, he left to join Raizing, where he programmed several of their more popular shooters, including Battle Garegga. After Raizing moved away from shooters, Yagawa joined Cave as not only a programmer but a director too, helming titles like Ibara, Pink Sweets, and Muchi Muchi Pork. All of these games have recurring themes, like the emphasis on rank, scoring by medal collection, and oblong-shaped bullets, making it clear that you’re playing a Yagawa shooter. The charge shield/bomb mechanic was also re-used by Yagawa in Pink Sweets.

Since Recca was created primarily as a tournament cartridge, it didn’t exactly receive wide distribution (though it did receive a retail release, unlike the Special Version releases of Hudson’s Caravan shooters). Both its rarity and its reputation as a technological powerhouse propelled Recca to become one of the most expensive games on the Famicom. It was, however, released internationally on the 3DS console, giving more people a chance to legally own it without shelling out several hundred dollars. The blurry visuals of the emulation don’t do the game any favors, and it’s not quite as impressive on the small screen, but it’s playable.