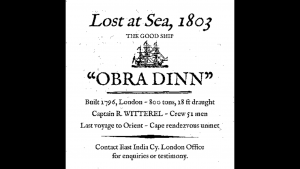

How do you follow up something like Papers, Please? How do you follow up one of the most successful, praised, and arguably influential indie games ever made? Lucas Pope’s answer was to do something completely different. Where Papers, Please was a stressful, commentary focused trek through a fascism daily life simulator, The Return of the Obra Dinn experiments in almost the complete opposite way. You’re still someone doing a job and affecting the lives of many others, but now you have all the time of the world, and what political exploration that’s there is relatively minor. The anxiety of realism is replaced with wonder and mystery of the unknown, and the end result is one of the most tightly designed and engrossing adventure games you might ever have the pleasure to play.

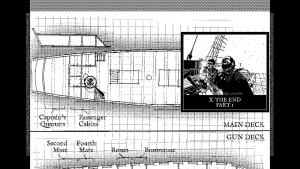

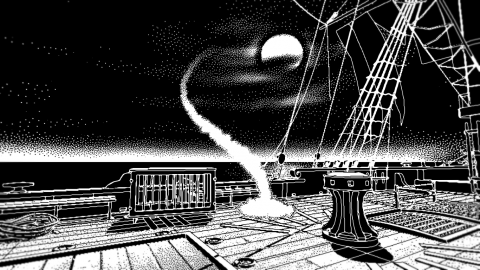

The game casts you as an investigator for the East India Company in the first decade of the 1800s, set out to investigate a now returned but long abandoned ship called the Obra Dinn. It’s been five years since it vanished, and now you have to figure out what happened to the crew. What makes this possible is a mysterious watch sent to you by a complete stranger called the Memento Mortem, which allows the user to return to the exact moment of someone’s demise when near their corpse or the area they died. The stranger dares you to figure out exactly what happened to everyone, promising to fill in the missing gap in the story after you do. From there, everything is up to your deduction skills – and you’re going to need them.

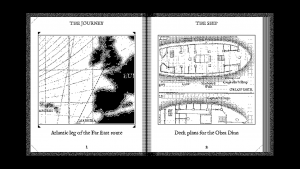

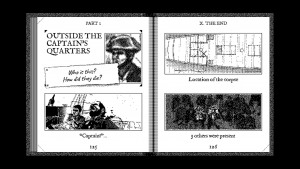

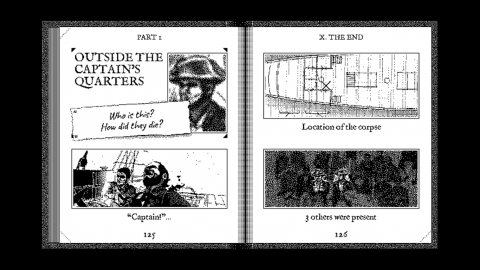

Unlike the also recently released Lamplight City, Return of the Obra Dinn doesn’t include the ability to ask people questions, nor can you pick up and hang onto clues to examine later. The goal is not to gather the pieces and solve the puzzle, but rather to make educated guesses with what information you can find across these various moments of death. The structure of finding all the deaths is pretty well set, with many unlocking in chains, but actually solving fates is incredibly open ended. The game does record some info in your note book, like what chapter of fates a particular character shows up, but the vast majority of what you need to solve each fate rests entirely upon the information supplied by the note book (such as the crew manifest and some drawings) and what’s hidden away in dialog, objects, and people found in the fate scenes.

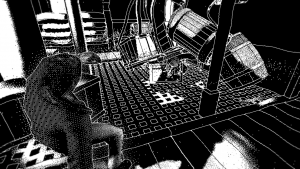

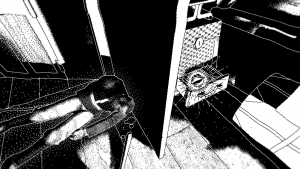

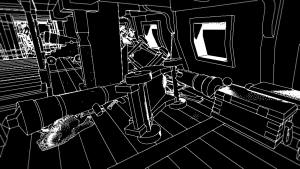

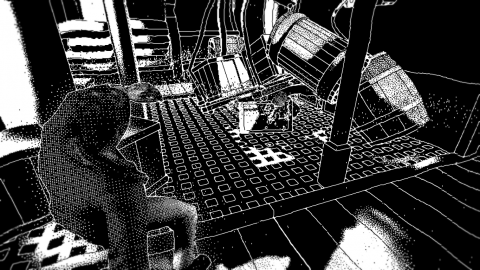

When you enter a fate scene, a black screen pops up as a bit of well acted dialog plays with text on screen (including other languages, due to the ship having several passengers from all over the world), and then you cut to the moment the current subject died. You can then freely roam around this frozen moment of time within a set area, finding other people who were in the area and piece together what was happening. When you feel you’ve figured out who someone is or how they died, you can record the information in your note book. Every three or four fates gotten correct, the game permanently records the correct ones and supplies you with some concrete information. It also un-blurs character portraits once there’s enough information available in the unlocked fates and the ones you’ve solved to figure out who said person was, with a ranking to one to three triangles to show how difficult a particular person will be to figure out. The catch to all this is that even if you get one identity or fate right, the game won’t let you know unless you solve a batch of three or four fates since your last one, which makes guessing a far less useful strategy.

What’s brilliant about the Obra Dinn is that every single piece of information you need is supplied to you. It will take a long time to figure out every fate, but it is completely doable if you put in the time and effort. The game is also extremely clever in how it conveys information. You’ll instantly spot a lot if you pay attention, while you’ll pass over information and not even realize it was there until much later. The time a fate takes place within a chapter, where a chapter is set against others, the grouping in a crew drawing, nationality and position listed in the crew manifest, odd lines of dialog, seen relationships with other characters, and much, much more all becomes vital to getting to the bottom of each mystery, with the far more obtuse ones become easier the more you figure out others. Answers are also often more simple than you may have expected as well, especially in “The Doom” chapter. Figuring out even one tricky fate feels immensely satisfying because the game design manages to avoid holding your hand while giving you just enough direction to start.

That’s not to say the design is flawless. Actually viewing fates you already unlocked, which you will need to do to advance, gets more confusing the more you unlock, as the ship becomes littered with fate spots that don’t signal which chapter scene they actually are. This makes trying to go to a particular scene a particular character was in a huge chore that kills the late game pacing significantly. Confusion also arises in trying to name causes of death due to the options you’re given. While some leeway is made by giving fates multiple solutions as long as you remain roughly in the ballpark, there are a few fates where the game becomes more picky. There are also moments where it becomes difficult to even understand what the cause of death was, and not always on purpose. This is due to the game’s odd graphical style, which sometimes makes it difficult to see details here and there when it’s needed, though these moments are very few and easily dealt with.

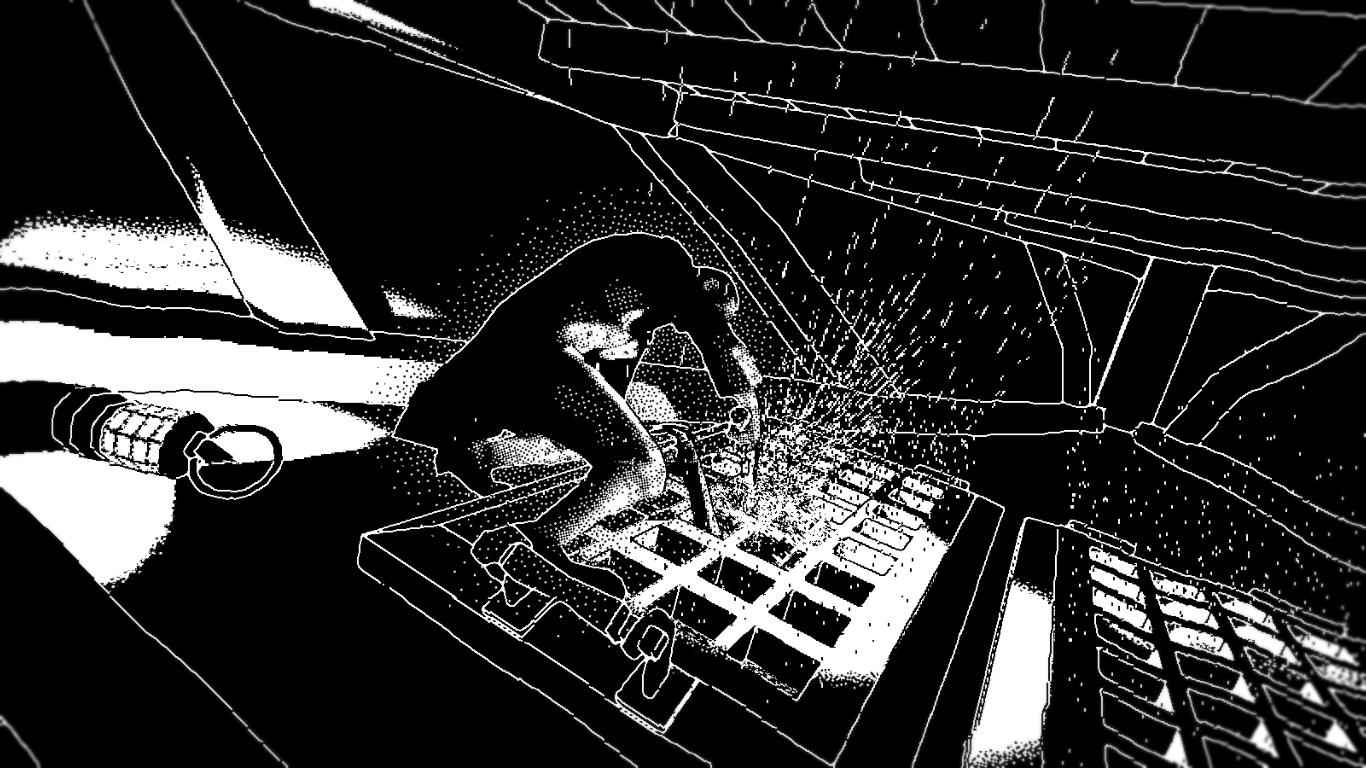

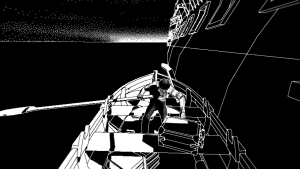

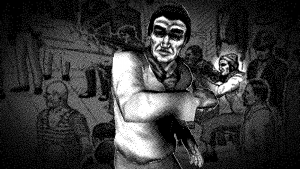

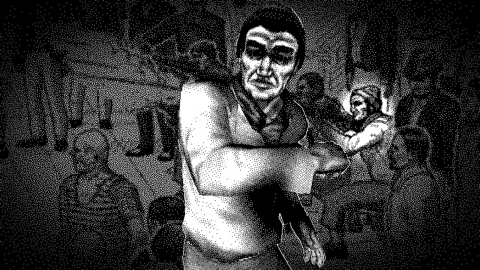

The strange 3D models with 1-bit graphic stylings on display are otherwise mesmerizing. It’s a step up from World of Horror, making three-dimensional space with two simple colors instead of creating 2D illustrations, giving the game a look like absolutely no other game out there. It also allows you to change filters, just like World of Horror and Downwell, which is appreciated for as long as you’ll be looking at the game for. The default Macintosh colors can strain the eyes after a few hours. The music is also stellar and well used when it pops up, creating a feeling of tragedy and high adventure, perfectly fitting the absolutely wild things hidden in the Obra Dinn’s past.

Despite the odd issues here and there, The Return of the Obra Dinn manages to come together to create an engaging pulp novel story you get to experience out of order, creating whole new surprises every few minutes of what’s already past for the story cast. Where Papers, Please was a branching drama focused on putting you through specific emotional states, the Obra Dinn is a who-done-it that wants you to be impressed with every single twist and turn it puts in its walls for you to discover. It’s not a thematically deep game, but it isn’t trying to be. It wants to be entertaining, the sort of game you just can’t pull down, and it succeeds in that goal with ease. It even manages to bring this feeling of adventure through its shifting tones, going from awe and shock to pitch black comedy at the drop of a poorly hung coat. An adventure game that manages to engage through its mechanics and game design and not mainly with narrative and art is rare, and they should be celebrated when they appear.