With contributions by Vyse the Bold, Pat R., and Sam Derboo

Music is just one of those things that touches the human soul on a subconscious level. Whether it be rock, rap, country, or techno, it gets the heart all fired up and often causes unpremeditated humming, singing, or dancing on the part of anyone listening. Not only rhythms and beats, there’s also an element that can’t be explained makes music so enticing. Something that also happens to be attractive is a myriad of bright colors and appealing visual patterns. The appeal of enticing graphics is easier to explain than that of music. People are drawn to exhilarating sights such as the water rush of Niagara Falls, a 4th of July fireworks display, or the naked form of a porn star.

And then there are video games, which incorporate pleasing visual and aural elements into their coding combined with the mechanics and rules of a game, to make a product that is appealing on many levels to anyone who plays them. However, graphics and music are oftentimes considered secondary to the core gameplay. We look back on the blocks and bleeps of the Atari 2600 and still find some fun in the games it has to offer, simple as they may be. And then there are modern games like Halo or Uncharted that still offer fun in blasting waves of enemies, only looking and sounding much more sophisticated. But most games could have simplistic graphics and sound and still have the gameplay intact and be just as fine titles to play. Rarely do games actually fuse the graphics and sound into their mechanics to the degree that taking them away would actually leave a much inferior game.

On the other hand, it is absolutely impossible to imagine Rez looking or sounding anything else than it does.

Good ol’ Sega released Rez in late 2001 for the Dreamcast and PlayStation in Japan. The game was made by Sega’s internal studio UGA (United Game Artists), the creators of Sega Rally 2 and the Space Channel 5 series. Sadly the Dreamcast went belly-up in America around the time of its release time, so only the PS2 version made it to the states in early 2002 for the PS2. It was a decidedly obscure title, however, with very little advertising, sold only few copies and generally went under the radar of most gamers. The print run was cut short, and prices zoomed into the stratosphere. Eventually, it became one of the few PS2 titles reprinted by Gamers Quest Direct, although it still goes for near full retail price even years after its release. Thankfully now there is Rez HD on the Xbox 360, as Rez is a gaming experience towards which no one should ever be ignorant.

Rez certainly doesn’t place its plot in the forefront. One super-intelligent information system known as Eden becomes too smart for its own good (dammit, hasn’t man learned from movies like 2001 and WarGames?) and becomes really confused about its existence. Eden shuts itself down and the Project-K network becomes corrupted by viruses. The player assumes the role of a computer hacker whose avatar goes on a decisive mission to blast through all the baddies in the system and bring Eden back into reality. There’s not a lot to the plot, but for there not being much, it’s pretty original as far as most game scriptwriting fare goes.

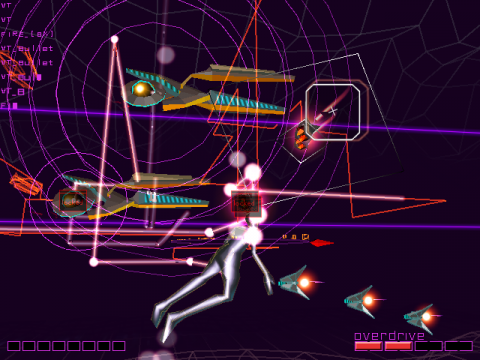

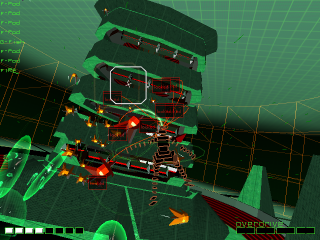

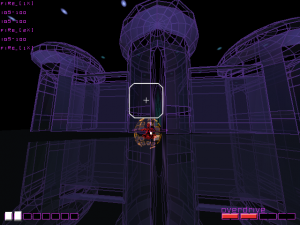

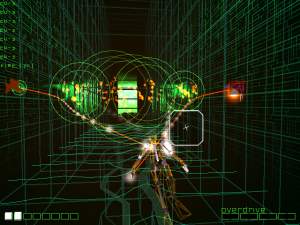

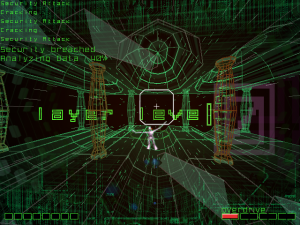

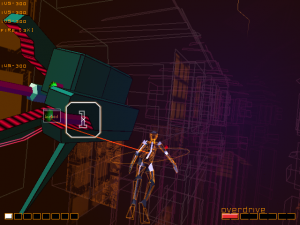

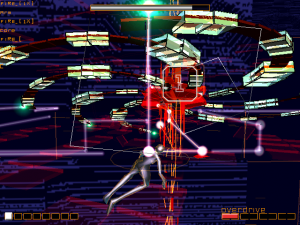

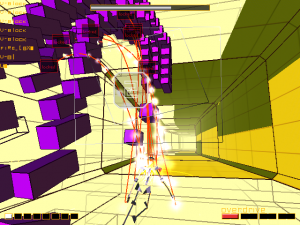

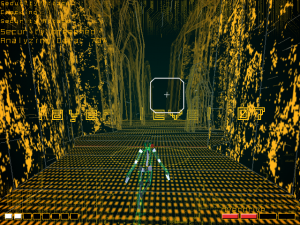

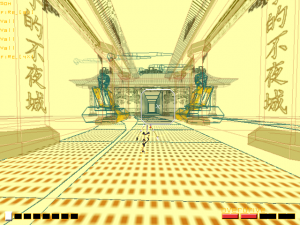

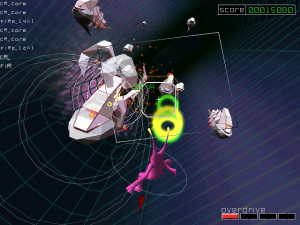

After all, 90% of all games just have plot as an exhibition that gives a reason as to why you play, and an explanation is expected when you’re flying about in wireframe landscapes and zapping polygonal antagonists. The visuals aren’t attempting to recreate some sort of fantasy world or post-apocalyptic warzone; everything is made out of simple polygons without much detail. This is not another world or universe; players are meant to be conscious of the fact that they’re actually in a video game. Well… technically in a virtual computer network, but that’s close enough. Rez certainly looks like no other game, nor does it sound like anything else, other than maybe playing Panzer Dragoon while on shrooms. Its graphics are minimalist, yet somehow intricate, and its sound is strangely entrancing. Probably why they call it “Trance” music!

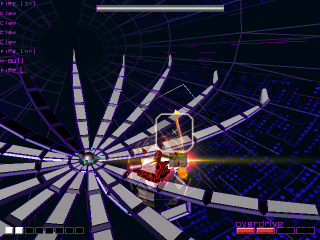

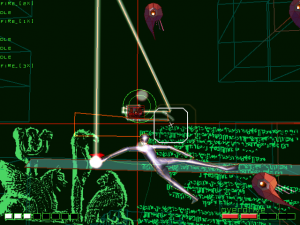

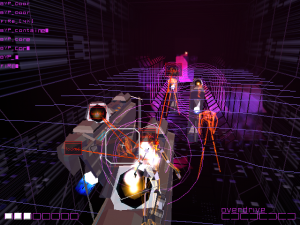

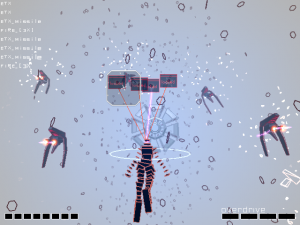

To get the basics out of the way, Rez does indeed play a lot like Sega’s seminal fantasy rail shooter Panzer Dragoon; almost exactly the same, in fact. The difference here is that there’s even less control over the avatar. Whereas the dragon in Panzer Dragoon follows the cursor around, the movement of the players virtual self here is mostly set in stone. Dodging is impossible save for very rare occassions, and all the control pad does is move around a cursor. This means that it’s essential to shoot down everything that poses an immediate threat. Either you blast the enemies before they fire anything, or you zap the missiles that they shoot before they reach the avatar. Only in certain stages it’s necessary – or even possible – to look around and stop enemies attackign from behind. Most of the time, the field of vision is limited to an extent of 150 degrees. The action thus is relatively simplified compared to Panzer Dragoon, but the genius about Rez isn’t insomuch about the mechanics as it is the execution and style.

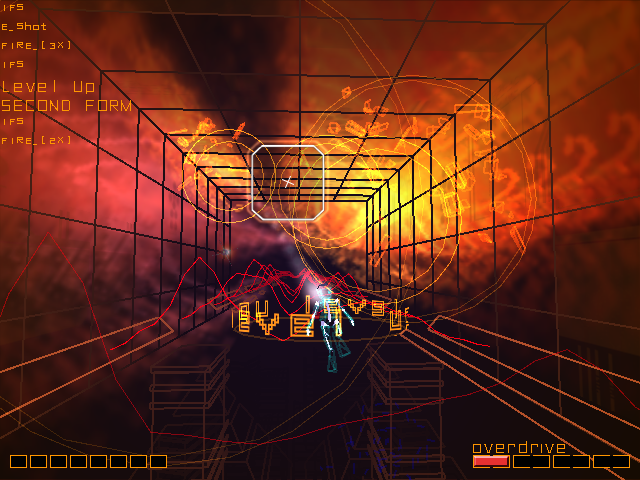

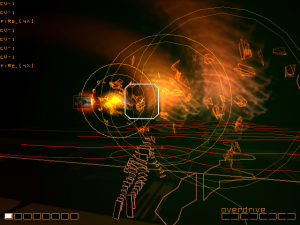

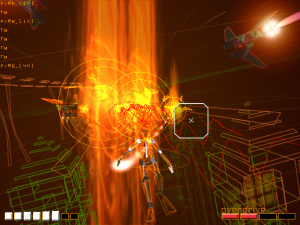

The first stage starts out as a blank dark red field with a slow hum of music – every piece of music is intentionally designed to roll along with the flow of the game and according to the player’s actions. Suddenly, a few enemies appear. Like Panzer Dragoon, the crosshair locks on to multiple enemies, and each targetting is accompanied by a quick percussion sound. Every action – locking on to a foe, firing the laser, killing an enemy – generates an electronic sound that compliments the compositions. When firing with a maximum eight targets locked-on, the sound made is that of an orchestral explosion, which sounds offbeat with the rhythm but is nonetheless cool. When baddies explode, they go down in a bright rainbow orgy of colors.

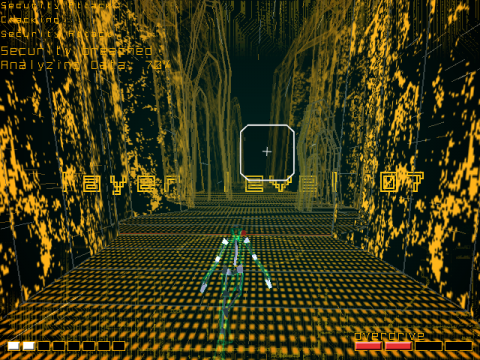

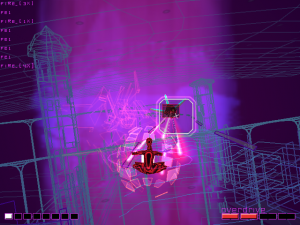

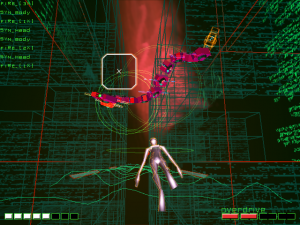

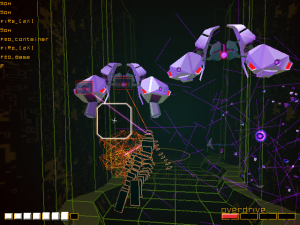

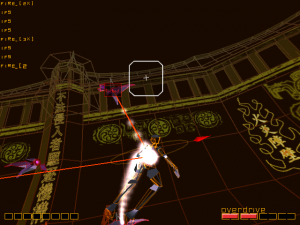

Soon more enemies pop up, and the music gets a bit bouncier as the hacker disposes of them. More fly in with faster speeds and quantities, and after they’re taken care of, a weird camera-like bot appears. This represents information gained from the system, and toasting them all is necessary to solve the game. Afterwards you move on to the next area, where the music is at a fairly speedy tempo and everything looks suddenly a bit more elaborate. There are ten areas total in each stage, which get increasingly detailed as you progress. By the later levels, the surroundigns seem like some sort of ancient cityscape, yet everything still looks computerized. Each area has a distinct look and color; the first stage is red and eventually becomes a pastiche of ancient Egypt. The second is purple and brings up spires from Arabian castles. Then follows an area dominated by green hues and models designs from ancient Greek constructions. The fourth stage is yellow and contains East Asian statues and temples.

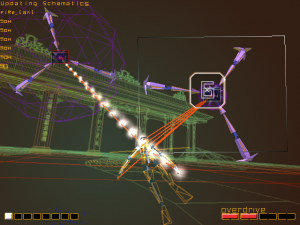

Similar to the graphic designs, the music gains more instruments and rhythms the farther in the journey goes. Next thing you know, the music is pumping like a professional bodybuilder and the eyes are mesmerized by a variety of shapes and colors. Eventually, the entire melody evolves into something different in the latter levels, yet the tempo is maintained. And then, when arriving at the boss, the tune changes entirely, but the speed still upholds its pace. It’s a vicious rave of brain-shaking insanity that one wishes would go on forever, but it has to end after the boss gets destroyed… or the player, whichever comes first.

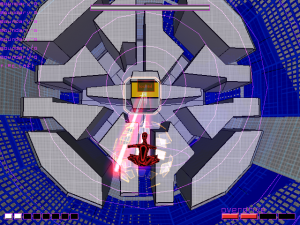

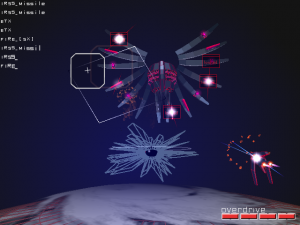

Speaking of boss fights, the end battles in this game are titanic struggles and true tests of reaction time. Doubtlessly the hardest part of any stage, each boss takes a hell of a long time to delete. It might take even longer, depending on how well one did leading up to the boss. If you’ve spent more time breaking bullets than eliminating enemies, the boss won’t be very aggressive, and he’ll take damage rather easily. However, if nearly all the enemies in the stage have been destroyed, the boss is harder, better, faster, and stronger – in that order. For every boss battle, the view becomes typically less restricted and it’s allowed to swivel around the avatar in full 360 motion.

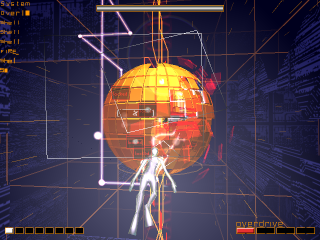

Boss 1: Earth

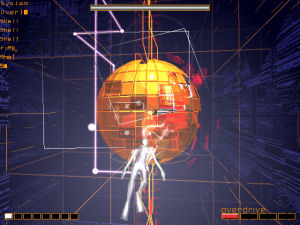

An aptly-named antagonist for its globe-shape at the time it’s first encountered (even though the other bosses are also named after planets). As the first boss, Earth is the easiest one in the game, but can still be somewhat tough in its latter phase. The globe-shaped thing it starts out as is pretty docile, but it soon grows barriers around itself that the player has to blast through.

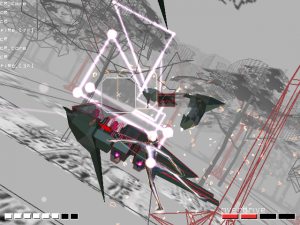

Boss 2: Mars

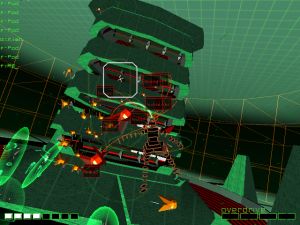

This formidable attacker can be pretty pressuring to fight in certain points of the battle. This multi-armed bastard can trap intruders within itself and force them to blast through many approaching gates before escaping. It also fires some weird plant-llike “branching lasers” from his tentacles, which can be the source of much aggravation.

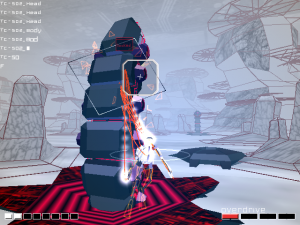

Boss 3: Venus

This battle can also be tough, if not for the fact that there’s less warning given than usual when it comes to its attacks. It also seems to be a bit more Panzer Dragoon-like than other fights for some reason. Venus starts off as a huge multi-paneled tower that fires lasers out of the red-eyed tiles, then it becomes a wall of artillery that fires missiles at the avatar, forcing it to fly away from it in an attempt to shake the projectiles off.

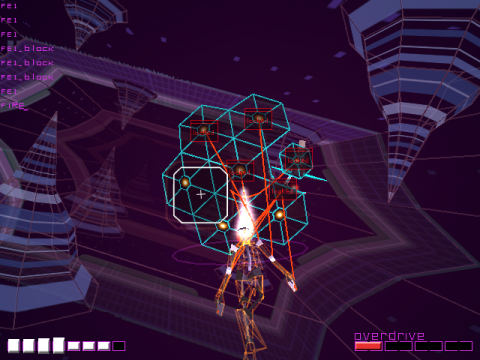

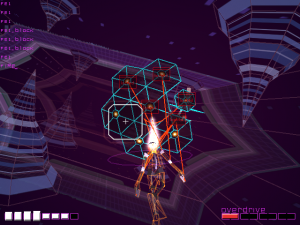

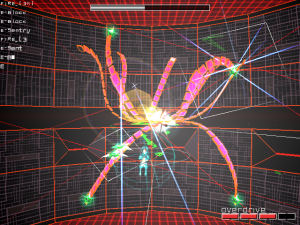

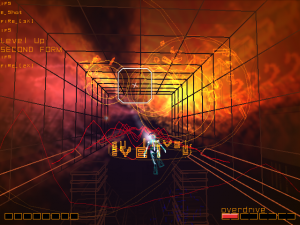

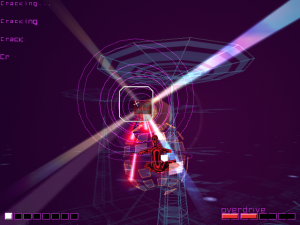

Boss 4: Uranus

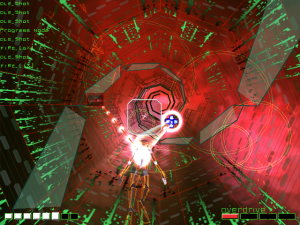

Uranus can be a real pain, even if at the same time it is the coolest battle in the game. It’s often hard to decipher its exact weak spot, and some attacks just seem unavoidable. Uranus itself is made up of many floating polygons that coalesce together to form various shapes such as a running man, a boulder, and a snake/dragon-thing. This is all taking place hurtling down a network of corridors at approximately 200 miles per hour, with hidden passages that contain spare powerups.

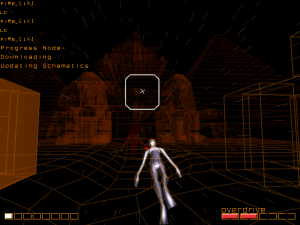

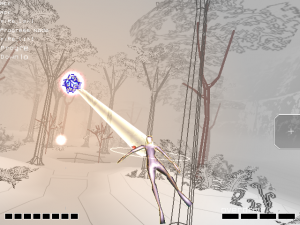

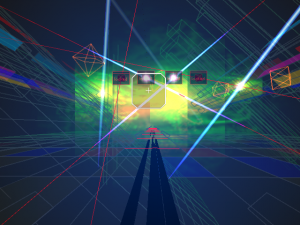

Once all four of the default stages have been beaten and all information has been extracted, a final fifth area is unlocked, where you get the chance to call Eden back into existence. It is, incomparably, one of the most breathtaking, messed-up, exhilarating, and even somewhat scary moments in the entirety of game history. It’s nothing like the stages that came before it, and it’s nothing like… well, anything else at all. It starts out as nothing but pure white dead space with flat geometric shapes and a few enemies floating around, but instead of the conventional data Protector, a circular gate appears in front of you with eight locks on it, which have to be blasted open immediately. You need to be ready to go, or you crash through the gate and take a hit. One already gets the sense that this isn’t going to be as user-friendly as the previous stages.

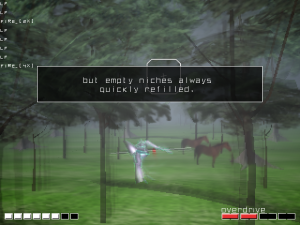

After passing through the gate, more dead space follows… when suddenly, an extremely realistic view of an ocean manifests as a cryptic mesage about life and evolution flashes by, and then you’re back in the virtual world, but things look ever-so-slightly more detailed. The stage carries on like this, going through jungles, deserts, and even through space, all the while further ominous messages appear. When moving on, one realizes that this is not ancient Egypt or Arabia or anything like that. Instead one is watching as the world itself and all life evolves inside the virtual computer mind. The music is a lot slower than the previous tracks, yet somehow more intense. Somber, yet heavy. Dire, yet pressuring. Unorthodox, yet deliberate. This really does feel like a final stage, almost like the end of life. And then comes the true final boss.

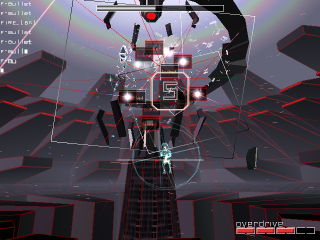

Boss 5: Eden

After all is said and done, the avatar enters the great white space where Eden once stood, and flies around her prison, where an armada of ships and missiles tries to prevent it from breaching the final line of defense. Each major hit delivered to the core reforms a part of Eden, causing her humanoid face to smile while a pleasant image flashes by the background.

There are a few different endings depending on the playre’s performance. When losing, Eden slowly shatters and falls into pieces. Even for the winners… well, the ending’s still pretty nonexistant. The only way to get the “true” ending is to get a 100% shot down rate on the final level – much easier said than done.

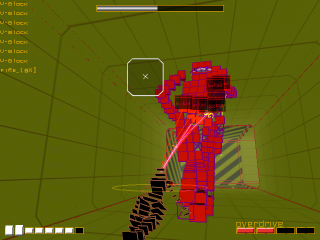

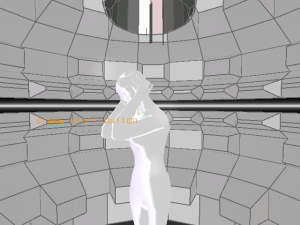

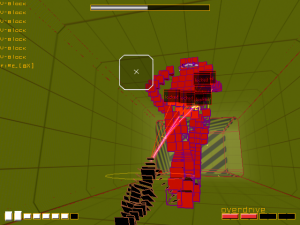

Right off the bat, the player’s virtual incarnation can’t take much damage at all. It starts out as a vaguely humanoid association of rectangles, but a hit degrades it to a pitiful specter made of triangles, and another will delete it entirely from the program. To increase the amount of damage it can take (as well as inflict), some enemies leave behind blue Progress Nodes. Cross-shaped ones add a single point to a PN meter, and the spheres give three points. Collecting eight points triggers a metamorphosis into a more defined humanoid that represents another hit and can do more damage. The next upgrade results in a full-form techno human who looks like a faceless Silver Surfer. After that follows the transformation into an impressive semi-sphere with the avatar sitting with its legs crossed and palms together, as if it were a meditating boddhisatva. The final upgrade turns it into an omnipotent full sphere pulsating with a stylish aura. Only for the final fight another form becomes available: A flying baby. The sounds the player’s shots generate also change with the form, ranging from a tinny electronic percussion tap to a bizarre robot voice sound on the highest level.

Unfortunately, Rez is a bit too short and not terribly difficult. Bad guys come quickly, but once they’re identified, it’s not hard to shoot them down. And if things become too intense, one can just activate the limited Overdrive attack to become invincible for a few seconds and zap everything onscreen. Adding to the similarities between Rez and Panzer Dragoon, the Overdrive attack causes a lot of damage and acts as a failsafe in the case that the amount of carnage becomes overwhelming. It doesn’t ever get quite as stressful as the Panzer Dragoon games, as one doesn’t have to worry about enemies coming from the sides or behind.

In order to add some replay value, Rez grades its players pretty harshly based on how many enemies are killed and how many items obtained. In order to unlock all of the cooler stuff, it’s necessary to get 100% completion rates, which is actually really hard. Some of the unlockable extras include two more play modes, Score Attack and Beyond. The Score Attack mode is like the Omake mode of many shoot-em-ups, which exists for those who aim to achieve the highest score possible in a run of a single stage. The Beyond Mode is a series of neat extras. There’s the obligatory boss rush, and for even bigger players there is Direct Assault, which encompasses all stages from beginning to end without any stop or save point. The Lost Area is a hidden level that has no boss but plenty of tough enemies to deal with. There’s also the very bizarre Trance Mission, where there is no player avatar, just the cursor zapping whatever may come along. It’s kind of an “ungame” such as Doodle City from the old Atari title I, Robot. This may sound boring, but it’s strangely attractive, as it features the trippiest visuals the game has to offer. It’s also possible to unlock a Morolian form for the avatar, a reference to the goofy dancing aliens in Mizuguchi’s Space Channel 5.

Once one gets past all of the simple-yet-entrancing graphics and the high-tempo techno, though, the core gameplay is really that of a simplified Panzer Dragoon. This game certainly emphasizes more on style rather than substance, and in most cases, this would result in a rather dry and boring title. But the elements in Rez just blend so damn well together, it’s almost as if the style and substance are tethered by the same delicate strand. When it comes to Rez, the visuals and music become an essential part to immerse oneself in the various colors swirling about while intense rhythms ring in the ears, and one finds oneself in an out-of-body experience, floating as a digital humanoid through the bleak cyberscape and doing what one does for the sake of doing it. All this without even the slightest dose of LSD. Can you believe it? If not, play it.

As mentioned, Rez for Dreamcast was released in Japan and Europe only, while the PlayStation 2 version was available in all territories. The Dreamcast version runs at a fluid 30 frames per second. The PlayStation 2 version is smoother, running at 60 frames per second, but tends to drop frames during the busier moments, especially during boss fights, and the graphics don’t look quite as crisp. Some claim that the Dreamcast version “sounds” better, but there isn’t much of a measurable difference. Other than that, both versions are identical. The Xbox 360 version, downloadable on Xbox Live Arcade, adds in widescreen graphics with optional high definition visuals. Not only is this the definitive version, but it’s much cheaper than its counterparts: It was released at a mere $10 price point, whereas the others often fetch $40 or more on the aftermarket.

A soundtrack was released called A Gamers Guide to Rez. Rather than containing music straight from the game, it includes all of the original music tracks before they were cut up and rearranged for the stages. After playing Rez a lot, they tend to feel a bit empty without all of the dynamic sound effects layered on top of them, but it’s still some damn fine trance music.

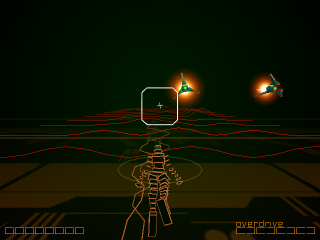

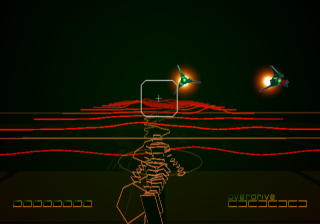

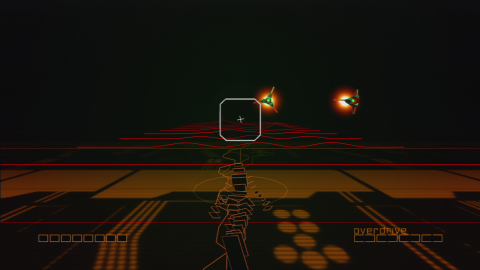

Screenshot Comparisons

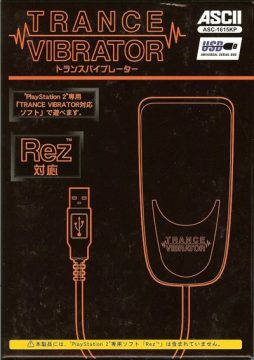

The Trance Vibrator

Since Rez is one of those games that attempts immerse the player as much as possible, Sega released an accessory called the Trance Vibrator along with the Japanese PlayStation 2 version of the game. The accessory is honestly rather odd. It’s pretty much just a stand-alone rumble pack that plugs into one of the PS2’s USB ports and pulses with the beat of the game’s music. The acessory has no way of attaching to the controller, though: It is not meant for the player, but for a second person watching, listening and feeling on, while the other plays the game. There are plenty of urban legends(?) on the internet about how people choose to “hold” it; the name itself is already suggestive as hell, after all. It works with the US release of the game as well, though it was never made officially available outside of Japan. Interestingly, the Trance Vibrator is also supported by Sega’s Space Channel 5: Part 2 (included in the Space Channel 5 Special Edition in the US) and Irem’s Zettai Zetsumei Toshi (Disaster Report in the US).

To borrow some words by Jerome Ashmore, who wrote a very comprehensive, not to mention complicated article on Kandinsky in the The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism:

For Kandinsky, the being of sound is spiritual and its status ultimate. He says, The world sounds. It is a cosmos of spiritually active beings….” “The world resounds and nothing is mute….” With sound conceived as ultimate, spiritual, and fundamental in abstract painting, there is a corollary that all physical things, if reduced to vibrations, will disappear and that what remains will be plastic elements in a pure state and, under the talent of the artist, amenable to revelation as sounds, movements, rythms, and emotional transports which give to each painting is particular resonance.

In Kandinsky’s view, all art is an attempt to tap into the “music of the spheres” (a term one might remember if one has ever read the Divine Comedy). Art utilizing vibration and sound is therefore the most pure, and abstract art consisting of carefully arranged points, lines, and color is the least distilled art form next to music. All art forms, however, are essentially groping for the same thing. Music and color are evidently just the most straightforward methods of achieving the goal that all art strives for: that which Kandinsky labels “inner necessity” and “soul vibrations.”

And now, for your indulgence, a final block quote from Ashmore:

By means of some simple examples, Kandinsky, in Point and Line to Plane, demonstrates the generation of sound in an abstract painting. If a point it placed in the center of a square, an observer hears a single sound. But, if the point is placed elsewhere in the square, two sounds occur, one the sound of the point itself and the other the sound of its off-center location in the square. If two points are placed off-center, the sound becomes more complex. From such an orgin, a storm of sounds can be created merely by adding points of various sizes in various places. The basic sound of any single point will vary with its size and shape.

Sound, Kandinsky believed, was the central feature of the universe. The realm of the spiritual manifested itself through vibration. Kandinsky therfore believed that music was the highest art form, and that all art in its various other forms should strive to incorporate as many aspects and elements of the musical condition as the artist could allow. If the other titles Mizuguchi has developed (Space Channel 5, Lumines) and his comment that the very first consideration during Rez‘s development was which musical artists and songs were to be featured, he seems to agree with Kandinsky’s sentiments in this respect. And if Rez‘s pulsing, flashing levels depicting the development of human civilization – and of all terrestrial life – are any indication, Mizuguchi kept in mind Kandinsky’s expressed notion that sound is a unifying force, the common root of content and form, of words and color, of art and science; the germ of the human soul, of life, Earth, and the universe in which we exist.

Apart from a belief in the significance of music and sound to his chosen medium, Mizuguchi also shares Kandinsky’s confidence in the sheer potential of music and video games. Kandinsky believed the fine arts could be used to usher in a new age in which the rediscovery of “forgotten relationships between the smallest phenomena and first phenomena will lead us finally to a cosmic sensation: ‘the music of the spheres.'” And during his official farewell to Sega, Mizuguchi is quoted as professing, “games are a very unique medium. They exist beyond language, beyond culture, and people are fascinated by games. I don’t know how long I will live, but I want to learn more about games.” Testuya Mizuguchi later went on to form Q Entertainment and produce more abstract music-based games, like Lumines, Every Extend Extra and even a spiritual successor to Rez, the gesture-controlled Child of Eden.

At this point most readers who haven’t played Rez are probably wondering about why an article about a video game is going on and on about some painter they’ve never heard of, while those who have played Rez might be slapping their foreheads and saying “Holy hell, it all makes so much sense!” like I did when I first stumbled over Kandinsky’s paintings and found out about their connection to Rez. If you’re already a Rez fan, check out more Kandinsky art as soon as you can.